Strolling the galleries at The Walt Disney Family Museum, visitors discover how brothers Walt and Roy O. Disney formed a business partnership in October 1923. They quickly began producing animated short subjects known as the Alice Comedies from a small office in Los Angeles. The pilot Alice story—which included a live-action young heroine played by Virginia Davis—was Alice’s Wonderland, and had been created months earlier by Walt and a small team back in Kansas City, Missouri. The subsequent Alice series adopted the same format as the proof-of-concept reel, that of a real-life girl in an animated world.

What’s lesser known is that when Walt arrived in Los Angeles with Alice’s Wonderland tucked away in his suitcase, he was unable to commercially release the film. It wasn’t that Alice’s Wonderland was a bad movie, but as the property of the soon-to-be bankrupt Laugh-O-gram Films, Walt could use it only as a calling card to entice a distributor to fund new productions. As he sent Alice out for consideration, he quickly began looking for other business opportunities in Hollywood

Still without Roy as a partner, Walt approached theater owner Alexander Pantages for permission to make an animated “joke reel” of topical gags, very similar to his early work for the Newman Theater in Kansas City. He began making the new joke reel alone, first in his Uncle Robert Disney’s garage, then moving into the back of a real estate office on Kingswell Avenue in early October. If it had been completed, this would have been the first movie Walt made in Hollywood. But in the midst of his solo effort, everything changed.

Margaret Winkler, a leading distributor of cartoons based in New York, replied to Walt’s inquiry with a contract offer to produce a series of further adventures about young Alice in her animated world. Walt was self-admittedly surprised, but he wired her back to accept, then realized he needed help. In the middle of the night, he visited the Veteran’s Hospital at Sawtelle, where Roy was convalescing from tuberculosis after his naval service. Awakening his older brother, he explained the situation and asked if Roy would go into business with him.

As historian Timothy Susanin would explain, “[Walt and Roy’s situations] changed dramatically overnight. On Monday, [Walt] went to the back area of [his Kingswell Ave. room] to continue work on a sample reel that he hoped would lead to work for Alex Pantages. The next day, he and Roy were partners in a studio that had an order for a series of cartoon shorts.” With their new commitment, Walt had to drop the proposed concept with Pantages. As of October 16, the contract was signed, and the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio was formed.

There was no time to reflect on the quick change of circumstance. Their first cartoon was due in only eight weeks, and their actress, the young Virginia Davis, was still living in Kansas City. Remarkably, with Walt’s encouragement the Davis family arrived in Los Angeles within a month—they had already been hoping to come west and find acting work for Virginia. Roy meanwhile commenced his financial management as they relocated into a larger office front on Kingswell in February 1924. The company’s first employee, Kathleen Dollard, was hired as an inking and painting assistant.

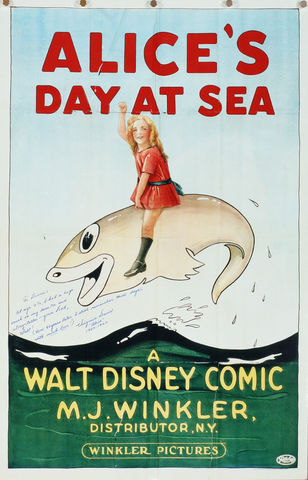

As the Davis family prepared to relocate, Walt had already started creative development on the first cartoon. Originally titled Alice’s Sea Story, the ultimate release was known as Alice’s Day at Sea and continued the format of placing a live-action girl in an animated world. This combination technique was quite a popular trope in the cartoons of the period, although Walt’s approach was a bit of a flip on the usual style of bringing animated characters into the live-action world.

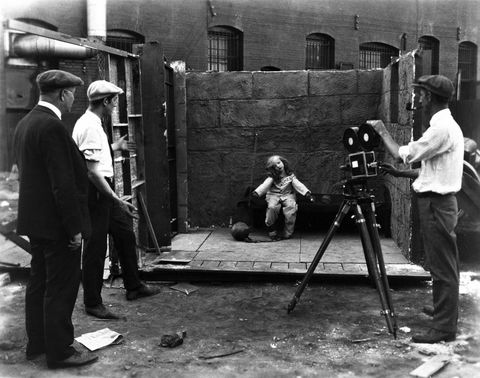

As historians J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt have described, “Whereas the animation and backgrounds of Alice's Wonderland had been the combined work of seven artists, Walt Disney wrote, designed and animated Alice’s Day at Sea singlehanded.” Dollard along with another new hire, Ann B. Loomis, were the ink and paint artists. Roy would be the camera operator for both the live-action and animation—something he had never done before. Walt had purchased a Pathé camera not long after his arrival back in August and subsequently made a custom animation stand out of found materials.

The story Walt devised opened not with a live-action girl, but a dog. A German Shepherd named Peggy—in real-life, Uncle Robert Disney’s pet—is asleep in her doghouse when the alarm sounds. In an extended live-action sequence, Peggy takes the clock in her mouth and throws it away, puts her harness on, and goes to wake up Alice at her bedroom window. The girl is astounded to see the dog pull up in a perfectly sized soapbox car. The pair are soon rolling off to the beach.

Arriving at the seaside (filmed at Santa Monica), Alice and Peggy greet a local sailor who treats them to a story about a shipwreck. This initial animated sequence is in a rudimentary style, white line on a solid black background, not unlike a chalkboard. It resembles some of the earliest animated motion pictures created nearly 20 years earlier by the English artist James Stuart Blackton, and Walt himself experimented in this style in some of his earliest animation while employed at the Kansas City Slide Company—later known as Kansas City Film Ad Company.

Inspired by the nautical tale, Alice and Peggy climb aboard a skiff that rests on the beach. Dreaming of becoming a sailor, the girl soon dozes off to sleep. Fading into the animated world, Alice dons a sailor’s cap and is greeted by an ensemble of musical fish. A sort of undersea carnival is taking place, complete with “King Nep’s Zoo” of exotic creatures—Walt’s love for animal gags is on full display here.

A whale-like creature then chases after Alice, who manages to find an automobile to aid in her escape. In a frightening twist, however, the beast swallows her whole, and soon makes another feast of a swordfish. But this newest prey cuts its way free from the inside, allowing Alice—and her crutch-laden automobile—to escape. In the last moments of her dream, a terrified Alice is confronted by a fearsome octopus, and soon awakens on the beach, entangled in a fishing net. When the sailor comes over to help her, the pair have a last laugh when Alice shares that she was only dreaming of being shipwrecked.

“I’d never seen the sea,” Virginia Davis would recall decades later. “That was a big experience for a youngster, all these waves. It was wonderful…” She’d also comment how Walt “would spin his stories around what was available,” from the Pacific Ocean to his uncle’s house pet. The film’s director turned 22 while finishing Day at Sea.

The film was delivered the day after Christmas, and Margaret Winkler did not pull punches in her feedback. “We agree with you when you say that this subject is not all that it was expected to be,” she wrote, “but as it stands it is a good picture. Of course, there is no use in going into details. I guess you know as well as I do, just what improvements it can stand. One big thing that I would suggest is that you inject as much humor as you possibly can.”

From the start, it was all about quality filmmaking. Winkler demanded high standards to stay on level with her other clients, Felix the Cat and Koko the Clown. Throughout his career, Walt would place quality at the forefront, no matter the pressure or tensions involved. He would spend more money on the second Alice film and work to grow his creative staff. It’s not clear that he ever intended to continue in a serious role as an illustrator and animator.

Roy’s days as a camera operator were also limited. As Kaufman and Merritt note, “[...] it had quickly become apparent that Roy Disney’s skill behind the camera was no match for his business abilities. ‘He never could master the cranking rhythm, a cameraman must learn,’ Walt Disney would later tell his daughter Diane. ‘As a result, we ended up with a fluctuating tempo on the screen, so finally I had to hire a real cameraman and that did cost more money.’”

The first in the formal series known as the Alice Comedies, Alice’s Day at Sea was released on March 1, 1924, and proved a success. There was no looking back. They had already finished their second film by the release of their first, and the upstart operation was slowly beginning to look like an established studio. Walt and Roy were borrowing money from friends and family to assist the operation and continued to live together in a small apartment. Roy typically cooked dinner while Walt continued work into the evening, and when they could afford it, the pair shared a meal at a local cafeteria.

As is the wonderful thing about history, absolutely nothing seems inevitable about these circumstances. The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio could very well have limped along for a short time and disappeared. But it did not, or in truth, they did not. The one new element in this situation was Roy, and in many ways, it would be the brothers’ partnership that fueled their resilience and determination. There were many, many struggles ahead, and they would tackle them together.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Walt Disney, Jeff Davis, Virginia Davis, and Roy O. Disney on the set of Alice’s Spooky Adventure, c. 1924; collection of The Walt Disney Family Museum

-

Margaret Winkler portrait, c. 1923; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives

-

Alice’s Day at Sea (1924) reproduction poster, with an inscription and autograph from Virginia Davis to Diane Disney Miller; collection of The Walt Disney Family Museum