It was late July 1923 and Walt Disney had failed. His Laugh-O-gram Films was headed for bankruptcy and, with little prospects left in Kansas City, Missouri, he was pulling up stakes. Hollywood was his destination. “Go west, young man, go west and grow up with the country,” the newspaperman Horace Greeley had written in 1865 (Walt would later quote this phrase to his friend Ub Iwerks, still back in Kansas City).

A young person taking a risk on a brighter future in Los Angeles was already becoming a bit of a trope in popular culture. Just a few weeks after Walt’s arrival, Paramount Pictures released a new feature entitled Hollywood about a young woman who travels to the city with her grandfather to break into the movies (no copies of the film are known to survive today). But Walt wasn’t venturing into the complete unknown. He had relatives in Los Angeles, his Uncle Robert Disney, as well as his older brother Roy, recuperating from tuberculosis at a local veteran’s hospital.

Walt was just 21 years old with a European campaign with the American Red Cross Ambulance Corps under his belt, but he had never taken a trip to the Pacific Coast. Under pressure from his company’s bankruptcy proceedings, he was struggling to cover the cost of regular meals, let alone a train ticket. “I used to go down and stand there with tears in my eyes and look at those trains out [of] Union Station,” Walt later told journalist Pete Martin. “I was all alone. It was lonesome, you know?”

To pay for the movie camera he bought and raise funds for his travel, Walt proceeded door-to-door in his Kansas City neighborhood, offering to take family videos as mementos for a small fee. He then sold his camera, and in spite of his dire financial straits, he purchased a first-class ticket aboard the California Limited. The night before his departure, he dined with Edna Francis, his brother Roy’s longtime sweetheart (and future wife). The mother-in-law of Walt’s older brother Herbert then gave him some food to take along on the trip, and her son drove him to Union Station the next morning.

“I came to Hollywood in a new pair of shoes,” Walt would say. “And I didn’t have a suit, because everything had gotten threadbare… And I had a pair of trousers and a coat, a checkered coat that didn’t match. … The suitcase was… kind of a frayed cardboard one. Well, in half of the suitcase I put what paraphernalia that belonged to me. All the rest I had to leave [in Kansas City]. And it was a big day the day I got on that Santa Fe Limited, this California Limited [train], and came to Hollywood. I was just as free and happy, you know. …. But I’d failed. I think it’s important to have a good hard failure when you’re young."

The California Limited was one of the iconic routes of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, having started operations between Chicago and Los Angeles over 30 years earlier in 1892. “The story of the Santa Fe is fraught with romance,” one writer put it just a few years before Walt’s trip. “Following the route of the famous old Santa Fe trail, this railroad has pushed steadily onward until today it is one of the world’s greatest railroad systems.”

Walt and his siblings became very familiar with Santa Fe locomotives during their years living in Marceline, Missouri, through which the railroad passed. A relative, Mike Martin, worked as an engineer for the Santa Fe, and a teenaged Roy Disney found employment as a news butcher for the company, selling treats aboard passenger trains (Walt worked the same job on smaller, regional lines).

By the 1920s, the Santa Fe was carrying thousands west as Los Angeles’ population doubled to more than one million residents. Former Santa Fe president Edward Payson Ripley—later the namesake for one of the Disneyland Railroad’s first locomotives—had been instrumental in establishing the California Limited as the railroad’s premier line. As a Santa Fe historian later described, “It was all Pullman [(an innovative passenger car design)] and you had to buy a ticket. No passes were allowed, and even Ripley, when he rode it, paid fare, just as everyone else did. In the summer, as many as seven sections, each consisting of 11 sleepers, pulled out of Dearborn Station [in Chicago] within half an hour every day—all full…. For more than ten years, the California Limited was the star limited train of the world.”

Settling into his upper berth aboard a Pullman sleeper car, Walt carried in his suitcase a reel of film containing Alice’s Wonderland (1923), the last cartoon he had made in Kansas City. Coincidentally, the California Limited was one of the first railroads ever captured by a motion picture camera. 25 years earlier in 1898, a crew from Thomas Edison’s traveling unit used a camera known as a Kinetograph—invented at the Edison laboratory—to film the Limited on the same westbound route that was carrying Walt to Los Angeles. Edison’s short “actualities” depicting true-life scenes around the world were among the first motion pictures to be commercially distributed (Walt himself became a great admirer of Edison).

Passing through the American Southwest under the hot summer sun, Walt had a close-up view of “a land of enchantment,” as a contemporary Santa Fe brochure described, full of “picturesque Indian pueblos” and “prehistoric ruins” all in close proximity to scenic mountain peaks and the Grand Canyon. Onboard, the Limited offered a number of amenities, including a gentlemen-only smoking and reading room, an observation car with multiple parlors, and even a full-time barber.

The one amenity that most passengers would have anticipated was the Fred Harvey dining-car service, offering three meals a day. In the late 19th century, entrepreneur Fred Harvey began partnering with the Santa Fe to open restaurants located at major stops west of Kansas City. Where—in earlier decades—western rail travel was notorious for its poor availability of food, these “Harvey Houses” offered affordable menus with fresh ingredients (courtesy of newly refrigerated produce cars). By the time of Walt’s trip, the Harvey service had been extended to Santa Fe’s dining cars. “It makes little difference what the season may be,” claimed a 1921 brochure, “Harvey’s chefs have at their command the food products of a continent.” (Roy Disney had in fact been a Fred Harvey employee during his time on the Santa Fe.)

As the California Limited crossed the Mojave Desert, Walt had his introduction to California. From Barstow, the train turned south and climbed the San Gabriel Mountains over Cajon Pass and down into San Bernardino. From there, it was a straight shot west to Los Angeles through small towns surrounded by citrus orchards.

In early August, Walt arrived at La Grande Station at the corner of 2nd Street and Santa Fe Avenue near downtown Los Angeles—where today the Santa Fe Avenue name remains and shops for the Los Angeles Metro rail line are nearby. The terminus of the Santa Fe in the region, the station was a peculiar building with a domed central roof inspired by Moorish architecture—a fitting introduction to the Hollywood realm of make-believe and fantasy. There, Walt visited Roy at the veteran’s hospital in Sawtelle where he convinced him to check himself out, setting the stage for them to co-found the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio. Uncle Robert’s home was nearby, and this would be Walt’s residence for the time being.

Settling into the small bungalow in the Silver Lake neighborhood, Walt argued with his sometimes-curmudgeonly Uncle Robert about the route his train had taken. “Our first argument was about how I’d come west,” Walt later explained. “As everyone knows, the Santa Fe Railroad is really the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. When I arrived, Uncle Robert asked, ‘Did you come through Topeka?’ I said, ‘I didn’t go through Topeka.’ ‘If you came on the Santa Fe, you did,’ he said. ‘Not the train I was on,’ I said. ‘It bypassed Topeka.’ Uncle Robert got hot under the collar at that but I wouldn’t give in. He had his wife call up the Santa Fe and when he found out the train on which I’d arrived hadn’t gone through Topeka, he was sore at me for weeks.”

From his childhood in Marceline to the fateful journey that took him to California, the Santa Fe remained a presence in Walt’s life. In 1948, he joined his employee and Disney Legend Ward Kimball on an eastbound trip on the Santa Fe Super Chief, one of the premier diesel locomotives of the era. Having worked at The Walt Disney Studios for over a decade, Kimball remembered his boss opening up in a rare moment of vulnerability.

Gliding along the Santa Fe—no longer a 21-year-old with few prospects but a 40-something with life’s travails weighing heavily on him—Walt told Kimball his life story. Their destination was Chicago, Illinois, where a massive rail fair provided a welcome break from the stresses of work. As they enjoyed the festivities, Walt was beginning to formulate ideas for a themed entertainment destination of his own.

When Disneyland opened just seven years later, the Santa Fe was there too, as the original sponsor of the park’s narrow-gauge railroad. Only a year before the Disneyland Railroad began its operation, the California Limited made its last run after 62 years. And would you believe it? Walt’s assortment of steam trains have now looped Disneyland for 68 years.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Santa Fe and Disneyland locomotive at Main Street, U.S.A. station of the Disneyland Railroad at Disneyland ; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation

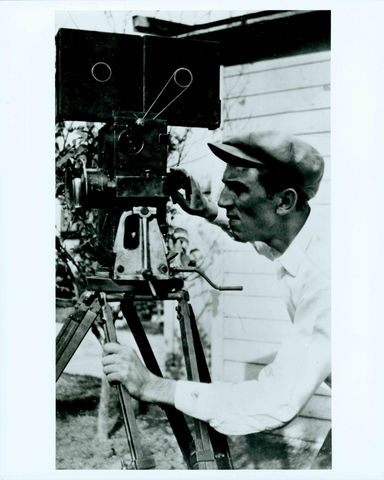

- Walt Disney standing behind a movie camera, 1923; collections of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library and the Walt Disney Family Foundation

- Walt Disney, August 1923; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation

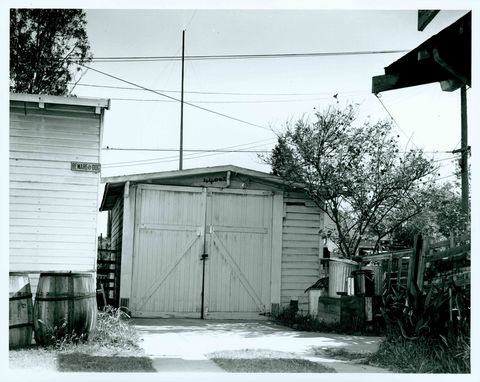

- Uncle Robert's garage, 1923; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation

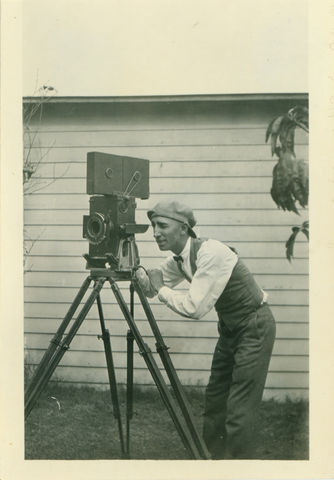

- Roy Disney standing behind a movie camera, 1923; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, Gift of Ron and Diane Miller