Watching Alice’s Wonderland, the short pilot cartoon Walt Disney carried with him on his journey west to Los Angeles in 1923, it's ironic to consider the character Alice’s own journey by animated train. The live-action young girl—played by Virginia Davis—makes a triumphant arrival in “Cartoonland” where crowds of cheering, hand-drawn animals welcome her with pomp and ceremony. Walt’s arrival in Los Angeles could not have been more different. Not only was there no glorious welcome, but the local motion picture scene could be called anything but “Cartoonland.”

Conspicuously absent from Hollywood in that moment was a major animation studio. The most popular animated cartoons in 1923 were being made in New York City, including Felix the Cat by Otto Messmer and Out of the Inkwell with its star character Koko (or Ko-Ko) the Clown by Max and Dave Fleischer—Margaret Winkler, soon-to-be Walt’s new distributor, had the contracts for both series. Walt became a particular fan of Paul Terry’s series Aesop’s Fables, with its cartoons full of gag-producing animals.

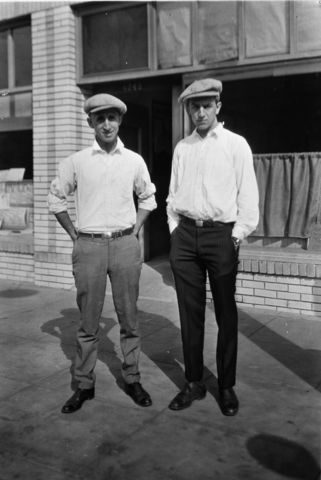

To establish an animation studio in Hollywood was to be on the outskirts of the filmmaking industry. There were few in the city with animation experience, and though Walt trained many new hires, he also persuaded a number of his Kansas City colleagues to venture west. Some would later depart the Disney brothers’ operation and become involved in other upstart animation studios, helping grow the medium’s presence in the city. All of them, Disney included, would also hire some of the best New York animators away from the East Coast to add to the growing talent pool. Within a decade, Hollywood was fast supplanting New York as American animation’s production center.

But that all seemed far away if not altogether unlikely in August 1923. Walt himself, at first at least, seemed eager to put his cartooning days behind him. “When I got to Hollywood, I was discouraged with animation,” he later said. “I figured I had gotten into it too late. I was through with the cartoon business.” Trying to “learn the [live-action] picture business,” Walt aimed to land any studio job he could in order to “be a part of it and then move up.”

One of his first stops was the Universal lot on the edge of the San Fernando Valley, where he could use the credential from his days as a newsreel cameraman in Kansas City to gain entry. There he spent the day wandering the Western backlot and New York street sets, but no job came of it. Over the coming days, he would visit the operations for Vitagraph, Chaplin, MGM, and Paramount. An old Kansas City friend at the latter studio arranged for Walt to be a horse rider extra on a new Western called The Light that Failed. “Well, it rained like hell,” he recalled. “So I didn’t get to go. And that was the end of my career as an actor. When they started all over again, they hired a whole new bunch.”

Throughout August and September, Walt moved around the studios on the job hunt, but to no avail. His older brother Roy seemed to think that he might have failed to earn a job in part because he spent most of his time observing and learning rather than pursuing an entry-level role. “I kept saying to him, ‘Why aren’t you gonna get a job? Why don’t you get a job?’” the elder Disney later recounted. “He could have got a job, I’m sure, but he didn’t want a job. But he’d get into Universal, for example, on the strength of applying for a job and then… he’d just hang around the studio lot all day… watching sets and what was going on…. And MGM was another favorite spot where he could work that gag.”

Hollywood in 1923 was in flux. The once quiet neighborhood had grown into the world’s filmmaking center. That year, Buster Keaton released The Three Ages, a parody of D.W. Griffith’s early blockbuster Intolerance (1916). Star actress Mary Pickford appeared in Rosita, the first American movie directed by German filmmaker (and recent émigré) Ernst Lubitsch. Just a month after Walt’s arrival, trailblazing director Lois Weber released A Chapter in Her Life with Universal. Other major releases that year included Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, The Hunchback of Notre Dame starring Lon Chaney, and a Western of epic scale, The Covered Wagon. Two separate films that year utilized the trope exemplified by Walt of a young person leaving home in search of new opportunity: the now-lost Paramount film Hollywood and Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last.

As historian William K. Everson would later describe, “Hollywood was financially secure; its films had size, dash, style, and beauty, and its stars and directors were popular box-office names the world over. Hollywood now ceased to be a mere geographic location; it became synonymous with all American film production.” Dominant studios were also emerging, a number of them as family-run operations. In April 1923, a few months prior to Walt’s arrival, four brothers from Ohio had established Warner Bros. Pictures Inc. Early the following year, brothers Jack and Harry Cohn—along with Joseph Brandt—changed the name of their C.B.C. Film Sales Company to Columbia Pictures.

Hollywood was not just a creative center, but an industrial one where movies were big business. As the studio system took shape, it became increasingly difficult for independent producers to establish themselves and compete. The leading artists Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, D.W. Griffith, and Douglas Fairbanks had already formed their own company in 1919—United Artists—as a means of resisting the creative control of studio businessmen.

“So…things began to look pretty hopeless,” Walt would say about his job prospects, “I then got my cartoon thing out again.” For most, there would be reason enough to despair. The movie business in general was hard enough to break into, and animated cartoon production was centered thousands of miles away. Many, including Walt, were dispirited with the state of the cartoon medium. It appeared that the best possibilities for story and characterization had already been achieved with characters like the ever-popular Felix the Cat. What else was there to do?

Although he was going back to his animation board, Walt would explain that he “decided to give cartooning another whirl and to put off being a [live-action] director until things loosened up.” These aspirations would be largely deferred more than 20 years until the 1940s when The Walt Disney Studios began making serious projects with live-action components, and by the end of the decade, entirely live-action features. Of course, in the meantime, Walt discovered that his early infatuation with animated cartoons was not unfounded. Far from settling with a novel form of entertainment, he pushed the animated film to unique realms of expression, inaccessible even to the dominant live-action medium.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Walt and Roy Disney, c. 1920s; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

- Walt and Roy in an office; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

- Photograph of Virginia Davis and others during the filming of Alice and the Dog Catcher (1924); courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney