Since childhood, Walt Disney had been a fan of the works of Jules Verne, including the author’s classic 1870 science-fiction novel, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. But later, as a film producer, he was not quite sure what he wanted to do with the story. After he had begun producing his True-Life Adventures, Walt started thinking that deep sea wonders, inspired by the novel, would make excellent material for a nature documentary. At one point, he even considered making it as an animated feature.

A chance meeting, likely in the summer of 1949 while Walt was in England to check on the filming of Treasure Island (1950), he met illustrator and Hollywood set designer Harper Goff at a London model shop called Bassett-Lowke, Ltd. Both were interested in buying the same model train, a passion they shared. A conversation over dinner led to Walt hiring Goff.

Harper Goff Sets a New Course

Goff also shared Walt’s passion for the Jules Verne novel, and he recalled that the 1916 silent version of 20,000 Leagues was his favorite movie as a kid, so Walt assigned him to work on the undersea True-Life Adventures project. Walt sent Goff to the Kerchkoff Laboratory in Corona Del Mar, California, to watch some exceptional underwater footage shot for Caltech's Marine Biology lab. With that footage as inspiration, Goff drew a series of storyboards while Walt was away from the studio. But they were not of the nature documentary film Walt asked him to do. Instead, he did a series of Jules Verne-style storyboards for the film he had always fantasized about seeing: a live-action feature of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. He had planned to take the drawings down before Walt could see them when he returned, but he was too late. Goff remembered a day when he returned from his lunch break and spotted Walt studying the storyboards.

Not unexpectedly, Walt was not entirely pleased that Goff had not done what he requested. According to Goff, Walt said, “‘When the cat’s away the mice will play.’ He raised one eyebrow, and I could see he disapproved of me doing all that, but I didn’t have anything to do and I was excited about the thing.” And the more Walt studied Goff’s storyboards the more he liked them. Part of Walt’s genius was that he trusted the talents of his artists and was always ready to consider interesting ideas they came up with. In this case, he was impressed enough to have Goff present his 20,000 Leagues storyboards, along with a presentation of The Great Locomotive Chase, in an A.R.I.—an “Audience Reaction Indicator”—to a group of film exhibitors who were in town. They would be told the story—illustrated by the storyboards—and give opinions about how the film might play to an audience.

The audience was more enthusiastic about the 20,000 Leagues presentation than they were with The Great Locomotive Chase, which convinced Walt enough to think about making 20,000 Leagues as a live-action feature. It would become the first fully live-action feature to be shot at the Burbank studio, and, at the time, the biggest, most expensive Disney film ever made. In fact, its final budget put it among some of the most expensive movies ever produced at that time.

20,000 Leagues’ Victorian-Era Costume and Set Design

Harper Goff, as production designer, would help to create the visual style of the film, including its centerpiece, Captain Nemo’s submarine, Nautilus.

Harper Goff’s vision for the look of the Nautilus, however, differed from Walt’s. It was a considerable departure from the cylindrical-shaped steel tube in the original illustrations from Jules Verne’s novel, which Walt expected. But Goff was able to convince Walt that it would be boring to look at onscreen, and to let him work on something more interesting.

For design ideas, Goff studied the novel in detail, aiming to interpret Jules Verne’s descriptions in a way that would be faithful to the original book, but also be visually exciting on film.

As the story takes place in Victorian times, Goff based his designs on available Victorian materials and construction techniques. He felt sure that Nemo would have used iron plates, fastened with rivets.

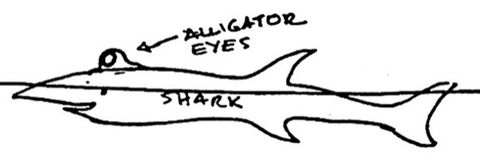

A major plot element in the book was that sailors on warships attacked by the Nautilus usually reported being attacked by some kind of sea monster. Except for early experimental submersibles, submarines didn’t exist in Jules Verne’s time. Goff wrote that, to him, the two most terrifying water monsters were the shark and the alligator, so he included elements of both in the design:

- The sleek silhouette of the Nautilus is very shark-like, with its dangerous pointed snout, menacing dorsal fin, and distinctive tail.

- The texture created by the iron plates and rivets on the surface suggested the alligator’s rough scaly skin texture.

- The upper portholes of the wheelhouse, covered by glass domes and lit from inside, suggest the eyes of the alligator that can watch you from above the waterline even when the rest of the creature is submerged.

In the book, Verne wrote that when the Nautilus attacked a ship from underwater, it drove a clean hole through the hull, so Goff designed the sawtooth spine on all the leading ridges around the hull—both a Victorian decorative element, and an effective cutting tool. The resulting look of the Nautilus, with its unmistakable silhouette, would make it an icon of “steampunk” design... over 30 years before the term “steampunk” was coined by novelist K.W. Jeter in 1987 to describe a style of fantasy fiction that featured Victorian technology, especially technology powered by steam.

Goff had a good idea in mind of what he wanted the Nautilus to look like, but he felt that sketches alone couldn’t completely capture what he envisioned. The best way to show Walt what he pictured was to make a three-dimensional model, so Walt could look at it from any angle. So, as he wrote, he “whittled” his first model over one Labor Day weekend. Precision wood carving was a longstanding traditional model making technique for vehicles in those days, from miniatures to full-sized car bodies. The main shape of the vehicle, called the “buck,” would have the finer details added. That model could be finished and painted to be presented as a one-off, or molded and cast if multiple, more permanent reproductions were desired.

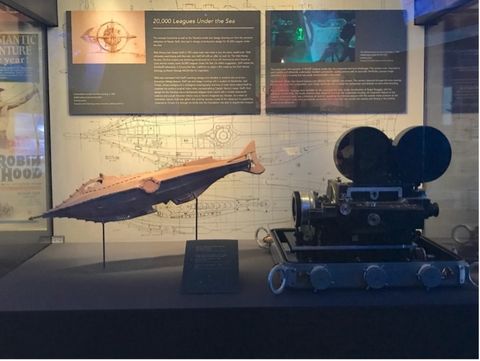

And Walt did indeed appreciate having a 3D model to refer to. He proudly displayed Goff's first model on one of his early Disneyland TV show episodes. Goff proceeded to create a second concept design model, refining a few details to make it much closer to what would become the final design. That model is on display in the 20,000 Leagues showcase in The Walt Disney Family Museum’s Gallery 7A.

Once the design was approved, that model would begin its work as the template for every model of the Nautilus needed to bring the submarine to life on film. Based on his model, Goff did large scale detailed mechanical drawings—on display in The Walt Disney Family Museum’s main galleries—that would serve to guide the plans for all the models and sets created for production.

20,000 Leagues’ Victorian-Era Costume and Set Design

In addition to the Nautilus, Harper Goff also designed the beautiful Victorian-style diving helmets and suits used in the underwater shots, that were not only visually innovative, but practical. With the assistance of diving expert Fred Zendar, he designed the suits to be built over functioning scuba gear—based on Japanese pearl diving helmets—so they actually worked underwater.

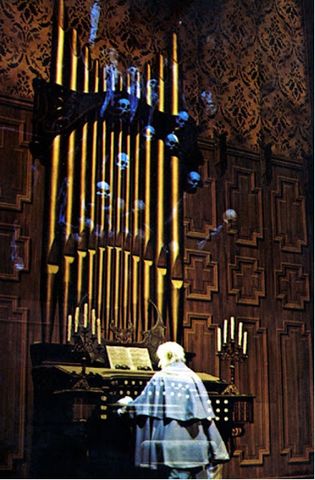

And he oversaw designs for all the interior sets of the Nautilus. Before he was hired by Disney, Goff had been a set designer at Warner Bros., having worked on many major films, including classics like Captain Blood (1935) and Casablanca (1942). The metal-riveted walls, the ironwork of railings, and the Victorian-style controls and mechanical devices are completely convincing as a 19th century submarine. He created standout set pieces like the huge, impressive viewport with its dramatic iris opening, and Captain Nemo’s salon—with its plush red upholstery and magnificent pipe organ designed by Academy Award®-winning set decorator Emile Kuri. Goff commented that nothing looks more attractive than a combination of rough iron and elegant luxury.

The Nautilus interior was eventually viewable by the public. Because 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) had been released theatrically the December prior and was still in theaters after Disneyland opened, Walt made the brilliant marketing decision to create a walk-through attraction, the 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Exhibit, featuring the Nautilus, which opened in Tomorrowland on August 3, 1955, just over two weeks after Disneyland’s Opening Day on July 17. He made use of the actual shooting sets, models, props, and matte paintings which were in storage since the production had long since wrapped. Walt intended the attraction to last around six months, but its popularity kept it open for some 11 years, until August 28, 1966.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea went on to win two Academy Awards®: One was for Achievement in Art Direction and Set Decoration, Color (there were separate categories for color and black-and-white films in those days). Emile Kuri received the Set Decoration Oscar®, and John Meehan, named in the credits as Art Director, took home the Oscar for Art Direction. Although Harper Goff functioned equally as Art Director, he is listed in the credits only as Production Designer.

Fun Fact: Haunted Mansion’s Organ

When the 20,000 Leagues attraction closed, future Disneyland attractions were already in development, and Imagineers looked for ways to repurpose parts of the set. And Nemo’s pipe organ—a main feature of the walk-through—can still be seen in the park. It’s the organ being played by a ghost in the ballroom set of the Haunted Mansion. It may not be immediately recognizable, because Emile Kuri’s decorative scrollwork was removed and the large fan-shaped pipes—which he added to the organ—have been replaced by straight pipes, which ghosts seemingly fly out of. But the main body is the actual organ from the film, an old electric theater organ purchased by Kuri through an ad in the San Fernando Valley Sun. (He did not inform the seller he worked for Disney, or that the organ was intended for a film, so he paid a mere $50 for it!)

Fun Fact: Nautilus Today: Paris and Tokyo

Disneyland Paris has a walk-through attraction in Discoveryland, Les Mystères du Nautilus, inspired by Walt’s original attraction, designed by Disney Legend and Imagineering creative adviser Tony Baxter with the assistance of master model maker Tom Scherman—who had dedicated his life to studying the Nautilus and befriended Harper Goff late in his life, when Harper was not well enough to work on the Disneyland Paris attraction.

A nearly full-scale Nautilus floats in the Discoveryland Lagoon, in front of the Jules Verne-styled Space Mountain. There is also a large Nautilus moored in the harbor of Tokyo DisneySea’s Mysterious Island area.

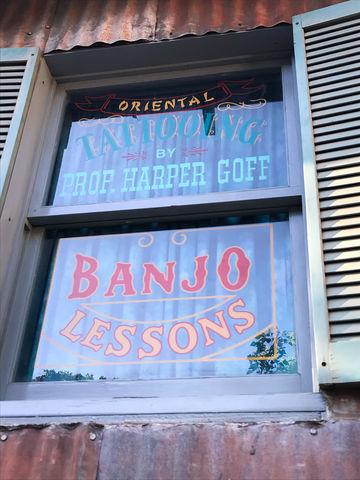

Fun Fact: Harper Goff, the Banjo Player

Another fun fact about Harper Goff is that he was a talented banjo player and performed with the Firehouse Five Plus Two—the traditional jazz group and founded by animators and Disney Legends Ward Kimball and Frank Thomas with other members from Disney’s Animation Department. Goff’s musical background came in handy on the set of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, when Kirk Douglas’s character, harpooner Ned Land, accompanies himself on guitar as he sings “Whale of a Tale” to the crew on the deck of a ship he has signed onto to search for the “sea monster.” Kirk could play the guitar a little, but he wanted more training in technique to be sure his performance in the film looked authentic. It was Harper Goff who gave him lessons! (It should be noted that Douglas’ unique flourish of twirling the guitar away from his body and back in was something he created himself.)

This particular skill of Goff’s is honored by a window at Disneyland. Goff’s window is one of the rare tribute windows that is not along Main Street, U.S.A., but instead located in Adventureland directly across from the Jungle Cruise attraction, which Harper Goff designed.

–Mark Siegel

A movie lover since childhood, Mark Siegel has enjoyed a storied career in entertainment, filmmaking, and visual effects for more than 40 years. He’s worked across the United States as a trained circus clown, actor, prosthetic and mask artist, sculptor, model maker, and computer graphics artist. He spent 26 years at Industrial Light & Magic working on dozens of iconic movies in both practical and digital effects, and for the last decade, he’s been a volunteer at The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (in order of appearance):

- Harper Goff, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) scrapbook, c. 1954; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Harper Goff, concept drawing for the Nautilus from a handwritten letter from Goff to Frank Johnson, 1974; courtesy of Tom Scherman

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea gallery display at The Walt Disney Family Museum

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) film still; courtesy of Walt Disney Archives; © Disney

- Haunted Mansion organ at Disneyland Park; courtesy of Walt Disney Archives; © Disney

- Harper Goff’s window at Disneyland Park; photography by Mark Siegel; Used by permission of Disney Enterprises, Inc.

- Nautilus at Disneyland Park in Disneyland Paris; photography by Mark Siegel; Used by permission of Disney Enterprises, Inc.