In terms of the actual production process, the film was fairly straightforward. The special effects were made easier by the fact that the film was in black-and-white. By far, the most challenging scene was the aforementioned basketball scene, which required 18 sets of wires and “was terrifying” according to Bill Walsh. Arthur Vitarelli, who often focused on scenes that required extensive special effects coordination, directed the segment after it was nearly cut by Robert Stevenson. Stevenson did not see the humor in the scene, but Walsh was adamant that it remain if it could be executed properly. Vitarelli recalled the long-standing issues that came with wires:

“So, I had quite a bit of experience with piano wires and with hiding the wires from the audience […] And nobody had thought about putting these basketball players on wires. Because up to that time they used to have […] one wire in the back [of the person]. And you were really limited with what you could do because you wanted to fall forward.”

To solve this, Disney’s special effects team designed a new mechanism that used two wires and gave greater mobility to the actors in the air. The design would be further improved upon during the production of Mary Poppins just a few years later for parts of the scene in which Mary Poppins, Bert, Michael, and Jane have tea with Uncle Albert—played by Ed Wynn—on the ceiling. Altogether, filming on the basketball scene took two weeks total to get everything just right.

The flying Ford Model T touring car that Professor Brainard uses throughout the film was another feat of the special effects team. Records from the film’s production indicate that the crew had at least three Model T cars—one that could be driven as a regular vehicle and two that were used to make the car “fly.” Vitarelli detailed the modification process that enabled them to minimize the Model T’s weight to allow it to be lifted into the air:

“We got a Model T Ford and we put aluminum fenders on it. We took out the engine, of course. We made a fiberglass crankcase, balsa wheels with foam-rubber tires, a screen for a radiator, a fake differential out of fiberglass. No upholstery. Everything was just bare. It couldn’t roll on the ground very well. You could just push it around without people in it […] But we had it strong enough that we could put four wires on it, and they went up to a platform […which was connected to] this big crane.”

At one point Wally Boag, best known for Disneyland Park’s longest-running stage show, the Golden Horseshoe Revue, also made a brief appearance in the film to assist with the special effects. During the dance sequence in which Professor Brainard dances up near the rafters of the college gym after attaching flubber to his shoes, Boag stepped in for MacMurray as his stunt double. Boag, being his typical comedic self, took things a little bit too far. “I did most of the tricks, especially dancing around with the leading lady. I did a rumba with her, and they would trap me up with a wire. I was wearing his mask, so I was Fred MacMurray for all those big leaps. I got a little excited one day when I thought of a new idea and when everybody went out to lunch, I got on the huge trampoline and when they came back, I was on the floor knocked out. I bruised the back of my head and I broke my wrist. They sent me to the hospital across the street and they fixed me up, so toward the end of filming I had a cast on, so I wasn’t out too long, I still did it,” recalled Boag.

Indeed, the special effects were so impressive for their time that Peter Ellenshaw, Eustace Lycett, and Bob Mattey—who were credited with leading the special effects on the film—were nominated at the 34th Academy Awards®. Mattey was paired with Vitarelli to handle all the flying sequences and other mechanical special effects. Despite The Absent-Minded Professor being Mattey’s first feature film credit, he had been in the industry dating back to the late 1920s. His nearly two-decade-long association with The Walt Disney Studios had begun in 1954 with his groundbreaking work on the mechanical squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) for which he designed the entire mechanical system that allowed the squid to move. Vitarelli recalled Mattey’s enthusiasm for his work, noting that “he would try and do anything.”

Notably, Walt was very invested in making the film believable or plausible. Certainly, a substance like flubber could not be created, but that did not mean that Walt could not convince an audience to believe that it could be real. Robert Stevenson noted the importance of this aspect of Walt’s creative process:

“We’re all very fascinated by Walt’s mind, or what we call Walt’s ‘illogical logic.’ He devoted a lot of thought to making people accept the impossible. In The Absent-Minded Professor, he let us work with a professor of physics on the concept of flubber. He let us put in quite a long and boring scene of the discovery of flubber, which made it seem apparently scientifically logical so that then people would accept everything from then on. I think you find that in all Walt’s magic stories everything is carefully prepared.”

Indeed, this was key to the film’s success. Flubber didn’t have to be realistic in the sense that it could actually be created—it just had to be believable. Walt even invited Hubert Alyea, a professor of chemistry at Princeton University known as “Dr. Boom” for his explosive presentations—whose lectures he had attended in the past—to come to the studio lot to give demonstrations.

—Parker Amoroso, blog contributor

Image credits (in order of appearance):

- Nancy Olson and Walt Disney on the set of The Absent-Minded Professor (c. 1961); courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library, © Disney

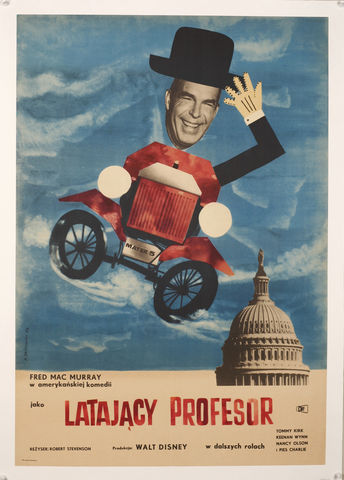

- The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), Poland release poster; courtesy of Walt Disney Family Foundation, Gift of Diane Disney Miller, © Disney