Released March 16, 1961, the film came in the middle of a record year for The Walt Disney Studios during which time Walt released three of the six highest-grossing films of the year—One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) came in at third while The Parent Trap (1961) came in sixth, just behind The Absent-Minded Professor—outgrossing notables like Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) starring Audrey Hepburn. Reviews were largely positive, with some critics even searching for a deeper meaning in the light-hearted, jovial comedy. Variety, for example, wrote that The Absent-Minded Professor was “enjoyable as an absurd, uncomplicated comedy-fantasy, but discerning film-goers may discover deeper, more significant humorous nuances… for beneath the preposterous veneer lurks a comment on our times, a reflection on the plight of the average man haplessly confronted with the complexities of a jet age civilization burdened with fear, red-tape, official mumble jumble and anxiety… a subtle protest against the detached, impersonal machinery of modern times.” Walt got a kick out of these sorts of reviews, telling Pete Martin of the Saturday Evening Post right around the film’s release, “Did you know a reviewer tried to read something into it? … yeah (laughing) … crazy guy… a kind of satire on our social… structure here, set up the way it is. The red tape in Washington… but it wasn’t, it was just a gag picture.” Leonard Maltin, well-known for his work documenting and critiquing Disney films, noted many years later that “[MacMurray] is inspired in the role. He plays his part with such utter conviction that you believe him completely—his naïveté, his absent-mindedness, his determination, and even his occasional stupidity.”

Similar to The Shaggy Dog and other Disney live-action films of the era, the film focused on quintessential period themes of American culture. Medfield, the setting of the film and the home of the fictional Medfield College of Technology, is a simple expression of small-town America. Professor Brainard, meanwhile, is an individualistic but largely misunderstood genius who does not typically consider what others might think of him—he keeps pushing forward with flubber no matter the cost. And, of course, the film keys in on many other themes running concurrently in the United States at the time, particularly the dawning of the Space Age, which had been in full gear following the launch of Sputnik I by the Soviet Union in 1957. Flubber, being an incredibly small but powerful substance with almost limitless energy applications, is very much a product of the “Atomic Age” which had begun less than 20 years prior. The film also makes light of the administrative and bureaucratic rivalry between the branches of the United States Armed Forces. In the film, a cabal of military leaders moves quickly to be the first to procure the professor’s invention for their branch of the armed forces all while projecting to each other that there is no way an invention like flubber could really exist. Military jets then almost mistakenly shoot Professor Brainard and his Model T out of the sky when he arrives in Washington. But these were hardly pointed or intentional messages. Walt’s films were for laughs and he wanted them to be on topics and material that his core audiences could identify with—small-town Americans juxtaposed against Washington bureaucratic shenanigans just happened to be a fertile ground for accessible comedy.

The film did generate a number of negative reviews, most of which focused on the plot being too silly or too far-fetched. Walt was not immune to these criticisms of his films, and he certainly did not fully ignore them. Richard Sherman remarked while talking about The Absent-Minded Professor, “Don’t let anybody ever tell you Walt was immune to a bad review. It bothered him!” But, at the same time, Walt and his team understood that Walt’s target audience was never the major film critics of the day—instead, it was the common, everyday American families that Walt had always identified strongly with. Walsh, intimating at this idea, explained his process for writing in an interview a decade later:

[MacMurray] is inspired in the role. He plays his part with such utter conviction that you believe him completely—his naïveté, his absent-mindedness, his determination, and even his occasional stupidity.

“[The comedies of 1950s and 1960s] were hokey pictures. But ‘hokum’ is not a bad word. I like to hear people laugh… Walt always said, ‘Try to learn what… you’re doing. You should go to the theatre in which your film is playing. You should go and listen to the show as much as you can and listen to the way the audience responds to the show.’ […] So [for The Shaggy Dog] I went to a theatre in Long Beach […] and it was about as dull as a place as you could want to go […] And there was a guy sitting next to me and he was a truck driver, apparently. Sleeves rolled up. He’s got a baby with him and the two are watching the picture. […] And then this wonderful thing happened. The kid started to laugh along with the father and there were the two of them laughing at the screen together. I thought that was better than the New York Times. And I said, ‘Boy, if I can do that, then I know what it is I want to do.’ … [Walt] liked to do that. He liked to go to small towns, which is sort of like what I like to do, too.”

Family entertainment with gags and laughs was what Walt and his staff were going for – not the reviews of highbrow movie critics.

This mentality worked well for Walt, and he was particularly pleased with the increase in adults coming to see Disney movies like The Absent-Minded Professor. Speaking right around the time of the film’s release Walt told Pete Martin that in “recent years we have increased the adult patronage of our, of our motion pictures […] they’ve realized that, that the things I build have an appeal to them too.”

Looking back 60 years later, The Absent-Minded Professor remains as funny today as it was when it was released. Its fast-paced storyline centered around wholesome gags and good, clean fun makes its humor timeless. While the Space Age may not have lived up to all of the dramatic expectations and predictions, it certainly provided the inspiration for some of the funniest family films of the decade. Just two years later, MacMurray would return for the film’s equally hilarious sequel Son of Flubber (1963). And MacMurray’s association with Disney did not end there. He also starred in Bon Voyage (1962), Son of Flubber (1963), Follow Me, Boys! (1966), and The Happiest Millionaire (1967). It truly was an exciting era for Walt Disney Productions. From live-action films like The Absent-Minded Professor to expansions and exciting new attractions at Disneyland park to groundbreaking animated films like One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), Disney was on a roll. It seemed like anything and everything was within the company’s reach—even flying Model Ts and flubber!

—Parker Amoroso, blog contributor

Image credits (in order of appearance):

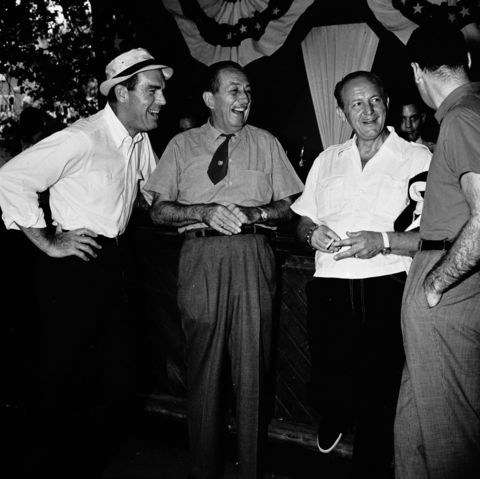

- Fred MacMurray, Walt Disney, James Neilson, and Elliott Reid at Golden Oak Ranch, 1961 ; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library, © Disney

-

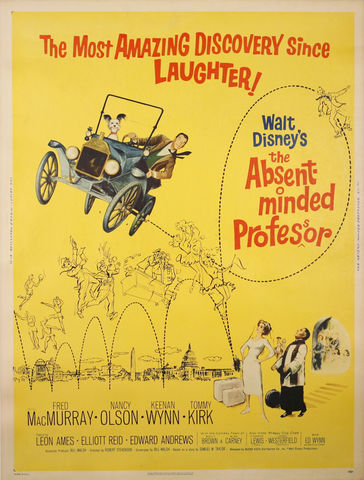

The Absent-Minded Professor poster, c. 1961; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation. © Disney