In the canon of Disney animation, Ward Kimball stands as the antithesis—the alternative to the traditional Disney style—what we may call “illusion-of-life” animation. Where such classic characters as Cinderella or Peter Pan were soft and refined, full of pathos and cognitive reaction, Ward’s characters exploded onto screen in an often illogical, zany, bold fashion that was always utterly original. His interests did not share similarity with his fellow Nine Old Men. Above all, Ward sought to have fun and inject as much humor as possible into his work.

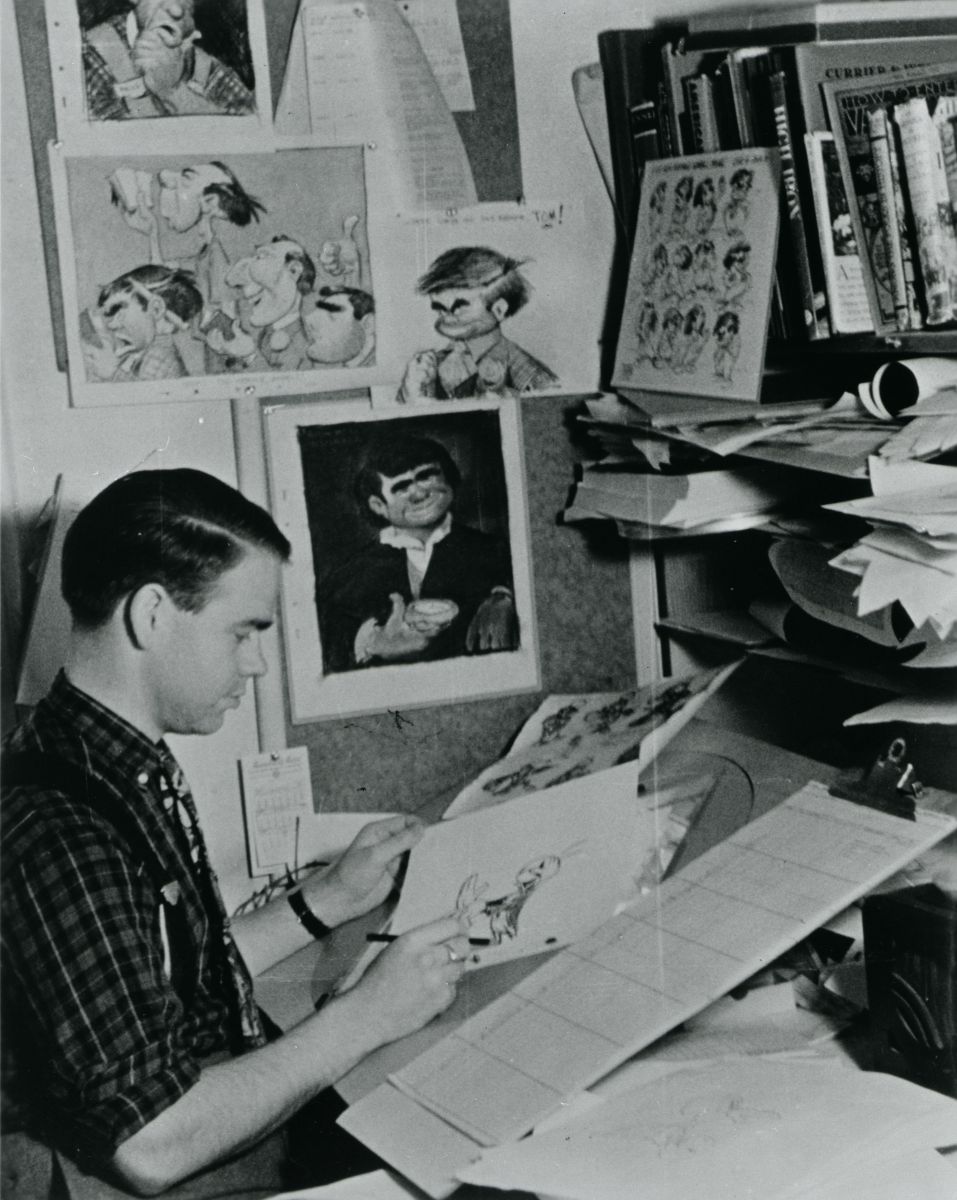

Beginning at The Walt Disney Studios in 1934 at the ripe young age of 20, Ward had originally hoped to be a background painter, but was put into animation instead. He soon proved to be a natural under the mentorship of those such as Hamilton Luske and Fred Moore. Had his two primary sequences not been cut from the final film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) might have been his breakout performance as an animator. It was rather on Pinocchio (1940) that Ward first shined best.

Beginning at The Walt Disney Studios in 1934 at the ripe young age of 20, Ward had originally hoped to be a background painter, but was put into animation instead. He soon proved to be a natural under the mentorship of those such as Hamilton Luske and Fred Moore. Had his two primary sequences not been cut from the final film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) might have been his breakout performance as an animator. It was rather on Pinocchio (1940) that Ward first shined best.

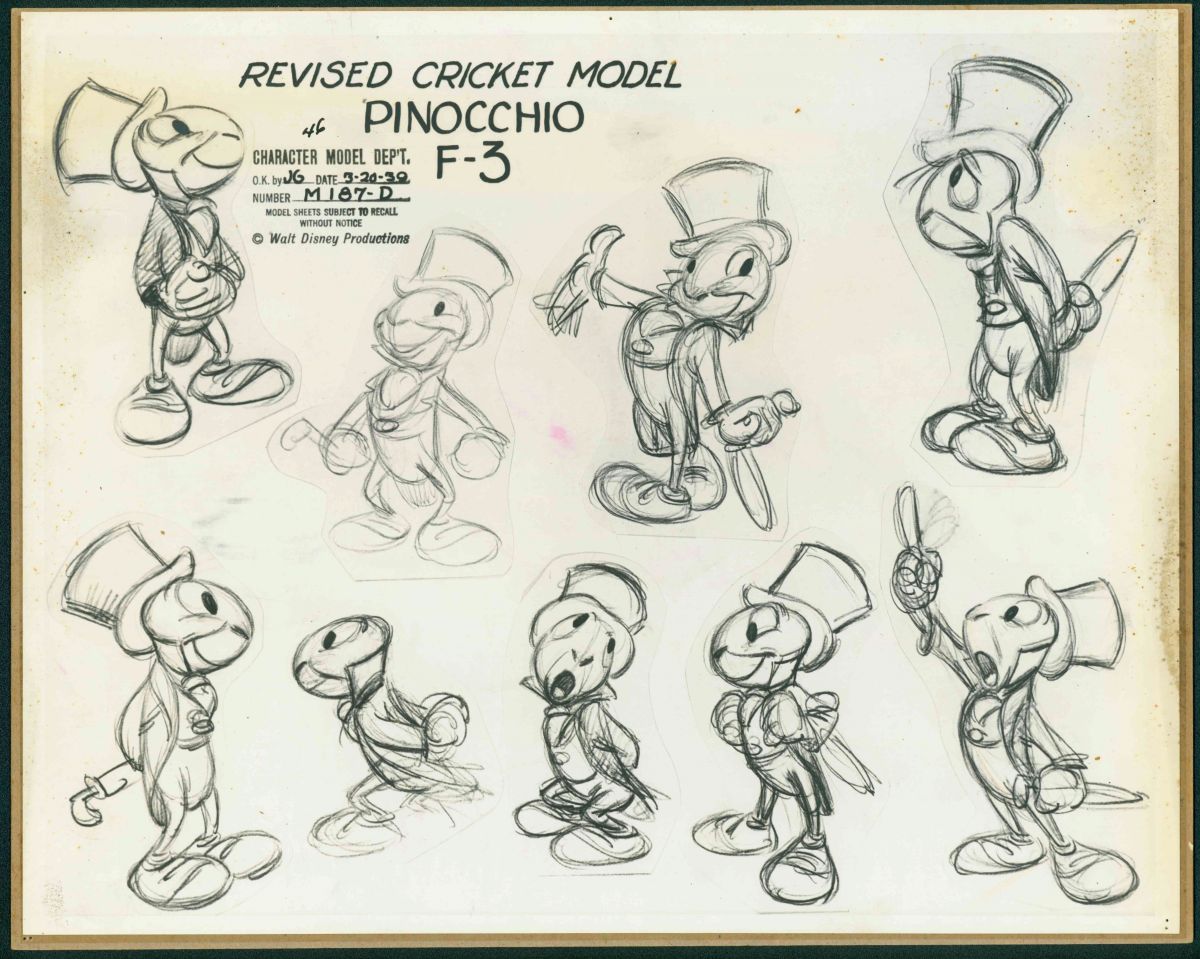

Jiminy Cricket may be one of the most memorable of all Disney characters, and Ward was the force behind his development and animation. Jiminy stands as Ward’s most Disney-esque performance. Full of pathos, this character may be, as historian John Canemaker describes, “arguably the warmest, most sincere, and psychologically three-dimensional personality that Kimball ever animated.” Jiminy is masterfully animated in the classic Disney style, though he still has moments of spunk and energy that would shine more so in Ward’s later characters.

Ward was a success in the wake of Jiminy Cricket, and he would rise in the ranks of Disney animators into the 1940s. In Fantasia (1940) he handled Bacchus in the “Pastoral Symphony.” In Dumbo (1941) he headed the unit responsible for the crows who teach the young elephant how to fly. With each assignment, Ward defined his own style of character animation more and more—a style that was slowly moving away from the Disney standard.

A truly unique moment of Ward’s animation career came in the title song sequence from The Three Caballeros (1945). “It’s one of my favorite sequences,” Ward would remember to historian Jim Korkis. A last minute addition, “Walt had said something like, ‘Give it to Kimball. He’s good with music.’ And I said, ‘Where are the story drawings? What do you want me to do?’ And they said, ‘We don’t know. Just do it.’” So Ward, ever in characteristic spirit, did just that.

A truly unique moment of Ward’s animation career came in the title song sequence from The Three Caballeros (1945). “It’s one of my favorite sequences,” Ward would remember to historian Jim Korkis. A last minute addition, “Walt had said something like, ‘Give it to Kimball. He’s good with music.’ And I said, ‘Where are the story drawings? What do you want me to do?’ And they said, ‘We don’t know. Just do it.’” So Ward, ever in characteristic spirit, did just that.

Following the lyrics literally, he animated Donald Duck, Jose Carioca, and Panchito performing as the written lines describe: “As they sang this song about themselves, ‘We are three happy chapies with snappy serapes,’ and the snappy serapes came in.” It was bold, a move of “iconoclastic gusto” as Canemaker describes. Though the staging seemed illogical, the scene flowed naturally and believably. Ward had created a sequence highly unique in the Disney canon, where story takes a step back and the zany wild possibilities of animation take a moment in the spotlight.

Perhaps Ward’s greatest moment as a Disney animator came in Cinderella (1950). As Lucifer the cat—Ward’s creation and somewhat alter-ego—searches desperately for the mouse Gus-Gus beneath some teacups, he soon realizes which one the mouse lies under, and erupts in a maniacal jeer. His usually slanted eyes become rounded, his paws shake with furious glee, and his head rocks crazily. It’s a moment not specified in a script or storyboard, or given by a director; it’s a moment only Ward Kimball the animator could have devised. Though only a few seconds long, it stands as a challenge to the style that so permeated the feature canon. Where refined and highly beautified animation reigns supreme, Ward Kimball injects hints of other possibilities with Lucifer’s ecstatic celebration.

Wild characters remained a staple for Ward in Alice in Wonderland (1951), with the Mad Hatter, Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, and Cheshire Cat. Historian Michael Barrier comments, “The other animators knew that Kimball was enjoying himself, and they resented it.” By the time of Peter Pan (1953), Ward was feeling untested by the current feature projects, as his stylistic evolution did not seem to match that of the Disney Studios. Both this difference of style, and Ward’s eagerness to move into a role beyond just animating, encouraged Walt to assign him the directing role on the special shorts Melody (1953) and Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (1953).

Wild characters remained a staple for Ward in Alice in Wonderland (1951), with the Mad Hatter, Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, and Cheshire Cat. Historian Michael Barrier comments, “The other animators knew that Kimball was enjoying himself, and they resented it.” By the time of Peter Pan (1953), Ward was feeling untested by the current feature projects, as his stylistic evolution did not seem to match that of the Disney Studios. Both this difference of style, and Ward’s eagerness to move into a role beyond just animating, encouraged Walt to assign him the directing role on the special shorts Melody (1953) and Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (1953).

As Canemaker explains, “Kimball was allowed to direct both shorts as he saw fit and his pent-up creativity exploded on the screen in two of the freshest works in Disney’s oeuvre.” These shorts were highly stylized, utilizing limited animation and modern designs then popular at rival studios. Ward was able to take the economically efficient style of modern 1950s animation, and essentially raise it to a level of Disney quality. What Ward and his crew were doing on films like Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom was so outside the regular Disney style that many, like artist John Hench, “thought Ward was going to get the ax for doing it.”

Next came what Ward considered “the creative high point of [his] career,” the space films produced for the Disneyland television program. Matching the stylized and limited animation with groundbreaking communication of space concepts proved perhaps the greatest of Ward’s work for Disney. Looking back today, it can sometimes be difficult to understand how important the space films were, both in style and content. Ward and his team were communicating crucial concepts that were as yet unknown to most Americans. President Eisenhower would request "Man in Space" (1955) to be screened at the Pentagon. That film along with "Man and the Moon" (1955) and "Mars and Beyond" (1957) stand as stark juxtapositions to other Disney films of the era, such as Lady and the Tramp (1955). Above all, they were very funny. That humor, along with the style, ensures best space's importance to this day.

In the 1950s, Ward Kimball was at the pinnacle of his achievements at Disney. But his individualistic spirit and independent mind did not ferment much support from others at the Studios. Moving into the 1960s, Ward would find most of his best work behind him. When Walt Disney passed away in late 1966, Ward started to become disillusioned with the future of the Studios. He would have one more piece of success, winning an Academy Award® for the short It’s Tough to be a Bird in 1969. He retired from Disney in 1973. For the next 29 years, until his death in 2002, Ward remained a passionate mentor of new animators and vocal proponent of the art form to which he had dedicated his career.

In a conversation between Diane Disney Miller and Pete Martin, Walt could be heard making a comment that has remained oft-repeated since: “Ward is one man who works for me I am willing to call a genius. He can do anything he wants to do.” Walt recognized Ward’s multifaceted style, whilst also recognizing Ward’s profound independence. Ward was his own man, as was Walt. Either did things in their own way, regardless of what others thought. Though they lead separate paths, their legacies will be forever intertwined—Walt the grand visionary, Ward the animated contrarian.

Lucas O. Seastrom served as a volunteer for two years before joining the staff as a Museum Educator in late 2014. He is a writer, filmmaker, and historian. His Disney studies can be found here.

Sources

-Barrier, J. Michael. Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Print.

-Canemaker, John. "Ward Kimball." Walt Disney's Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. New York: Disney Editions, 2001. 80-123. Print.

-"Interview with Ward Kimball by Jim Korkis." Walt's People. Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him. Ed. Didier Ghez. Vol. 2. N.p.: Xlibris Corporation, 2006. 74-104. Print.

-Miller, Diane Disney, and Pete Martin. The Story of Walt Disney. New York: Disney Editions, 2005. Print.