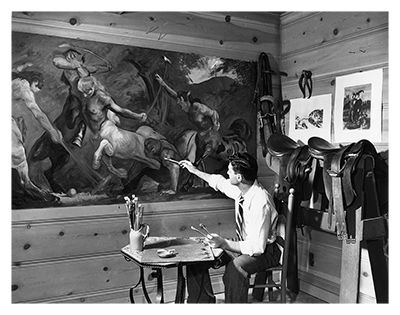

“What I really wanted to be was a cowboy,” artist Mel Shaw said about his first boyhood dreams. However, after a brief stint on a working ranch during his high school years, the young man realized he in fact had other ambitions. Shaw’s life as an all-out renaissance man produced a near overwhelming amount of artistic creations, from painting to sculpture to sketches and pastels, many of which are exhibited in Mel Shaw: An Animator on Horseback at The Walt Disney Family Museum. The fascinating works on display include a selection of Shaw’s work when he was working for Walt during the Studios’ golden age.

The Walt Disney Studios of the late 1930s and early 40s was a bustling environment of artistic exploration. As Shaw described the period, “[…] everything was very exciting and inspirational. I think that you could call [that] the golden era of animation. Like if you talk about the Renaissance and all the artists that were working at that time in the early Italian Renaissance, I would say that that might have been the Renaissance of the animation period.”

Though Shaw joined the Studios in 1938, he was already an animation veteran by the time he arrived. Having studied at the Otis Art Institute (where he studied alongside fellow future Disney artist Tyrus Wong), Shaw took a job at Pacific Title and Art Studio while still a teenager in the early 1930s. There he worked on animated films with Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising, old friends of Walt from Kansas City who had recently left Walt’s organization. These were the early days of what audiences would later know as Looney Tunes.

By the late 1930s, Shaw had picked up the equestrian sport polo among his many hobbies, a passion he shared with Walt. “I was playing polo semi-professionally for the Riviera Country Club,” Shaw remembered. “Walt had a membership there, and he was playing there, and he knew that I was one of the animators of Harman-Ising […] He asked me what I was doing, and I told him, ‘Nothing now.’” Walt, ever on the lookout for the best talent, soon hired Shaw to come work at his studio. After Shaw arrived, Walt said to him, “You like to draw animals, would you like to work on this? We just got the rights [on] Felix Salten’s Bambi.”

Bambi (1942) had originally been planned as Walt’s second feature film, but the story’s visual complexity drove Walt to delay the film’s production to allow his artists time to better their skills. Shaw, described by animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston as “a true natural artist who was particularly sensitive to the visual possibilities in the surroundings as well as to the appealing actions of characters,” joined the Bambiteam as a story and conceptual artist. He contributed to the development of key scenes, offering his talents to envision—among other things—the memorable rainstorm sequence. He produced an exquisite array of pastel, ink, and watercolor studies for the film. These pieces were often impressionistic and full of possibility for animated adaptation. One scene, in little clouds of blues and greens, highlights one of Bambi’s mysterious encounters in the forest. Another character study portrays two grasshoppers in detail, their rich color almost electric with energy. Most charming of all was perhaps a study of young Bambi amongst a growth of cattails, quizzically inspecting a little insect friend nearby.

During his early time working on Bambi, Shaw and the rest of the crew did not work at the main Hyperion Studio, but rather at an annex building on nearby Seward Street. There, the Bambi team was left more or less on its own, allowed to slowly develop and conceptualize what would become Walt’s most individually unique masterpiece yet. Shaw and his fellow artists jokingly felt like outcasts at the annex, and a humorous caricature on display in the special exhibit memorializes one of Walt’s infrequent visits from down the street. Eventually the Bambi team would be among the first Disney artists to move into the new studio lot over the hill in Burbank.

“I think the best education I ever had was during that particular period of time…” Shaw said about this period at the Studios. “…because of the type of artists that were coming into the studio.” On Bambi, Shaw befriended and worked with legendary artists like Marc Davis and Retta Scott. They would often make field trips to a nearby zoo to develop their ability at drawing animals. “I still had a little bit of the old cartoon in my drawings,” Shaw recalled. “But they became more refined as the people who were working on it were learning more about animal drawing.”

Following his work on Bambi, Shaw moved into production on what would become the Wind in the Willowssegment of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), though he and his friends anticipated they might soon be working on another feature. Shaw remembered, “[…] The one sketch that I had of Carl Fallberg and Marc [Davis] and myself. That’s because we thought we might be going on Alice in Wonderland [1951]. And the three of us were working together […] So I made that sketch of the possibility of it.” The rather outrageous piece, on display in the Animator on Horseback exhibition, portrays Fallberg as the Mad Hatter sneering towards Shaw as the March Hare, with Davis below as the mouse. These and other delightful artworks showcase the use of caricatures and exploration of creativity at Walt’s studio.

“I liked Wind in the Willows better than I did Alice anyway,” Shaw declared. He would spend months helping to develop the Kenneth Grahame classic for the screen. Willows would enter production in the early 1940s, but outside events contributed to its ultimate delay (along with other projects like Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan [1953]). The animators’ strike of 1941 was a major moment and Shaw, relatively indifferent to the politics of the situation, chose to leave at this time to collaborate at a new studio with his old boss, Hugh Harman. Though Shaw “never saw Walt again” after that fateful summer, Walt never forgot Shaw’s immense talent, and continued to reach out to him in succeeding years for various projects.

“One of the things that Walt always liked us to do was to get everybody involved,” Shaw observed. “So we used to call in other people from other departments and get their input on an idea or sequence [….] It would help a lot.” But Shaw wasn’t the type destined for a lifelong career at Disney, although he would return in later years to inspire a new generation of Disney artists with his extraordinarily beautiful concepts, leaving his unique and indelible mark on the films they made. Like the cowboy he had hoped to be as a boy, he remained a wanderer, roaming from project to project, both on his own and at other studios and companies. But as the beloved storyteller, J.R.R. Tolkien once wrote, “Not all who wander are lost.” The special exhibition on display at The Walt Disney Family Museum is evidence enough for Shaw’s wonderfully prolific career.

Mel Shaw: An Animator on Horseback is organized by The Walt Disney Family Museum and is made possible by the generous support of the Diane and Ron Miller Charitable Fund and will be on view from January 13 through September 12, 2016 in the Theater Gallery.

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for the Walt Disney Family Museum.