When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Walt Disney had been busy challenging commonly-held perceptions about animated cartoons. A medium once largely relegated to novelty, Disney’s animated films offered drama and pathos along with humor and song. Walt spent more than a decade elevating the art form to new levels of technique, performance, and quality. In just a few short years, The Walt Disney Studios had created multiple feature films of astounding range and style—from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Pinocchio (1940) to Fantasia (1940) and Dumbo (1941)—that only seemed to promise more to come.

With war came disruption. Existing plans were set aside for new government projects. The war effort presented a different creative challenge: how to make animated cartoons that convinced audiences of ideas. Emotion had to be coupled with persuasion. Walt and his artists found themselves supporting projects making propaganda—one of the strongest examples of which was the short subject Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943), a raucous indictment of fascism starring Donald Duck.

Absent the emotional timelessness of other Disney films, Der Fuehrer’s Face exists today as a piece of history that illustrates the prevailing moods and feelings of a specific moment. As historian Leonard Maltin explains in his introduction to Der Fuehrer’s Face for the “Walt Disney Treasures” collection DVD set: “We still see this today whenever a dictator or despot comes to power anywhere in the world. Caricatures and jokes—not always in the best of taste—rise to the forefront because it’s our way of relieving aggression.”

Making Light of the Enemy

WWII Disney Propaganda: Oliver Wallace Composes a “Novelty Smash”

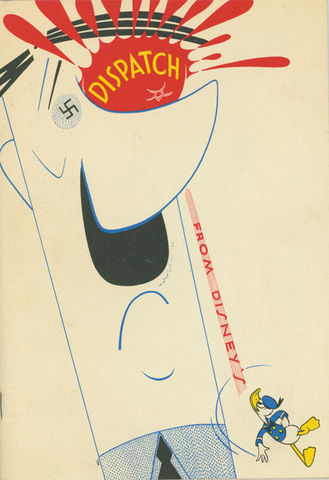

On a seemingly normal afternoon at the Disney Studios in 1942, Disney Legend and composer Oliver Wallace encountered Walt Disney in the hallway. As Wallace recounted in the Dispatch from Disney’s, a 1943 booklet sent from the Studios to Disney employees serving in the war, Walt said, “Ollie, I want a serious song, but it’s got to be funny!” Wallace did not understand what the boss was referring to. Walt briefly explained about a short cartoon sending Donald Duck on an adventure in “Nazi land,” which “didn’t help very much” for Wallace’s understanding. “Suppose the Germans are singing it,” Walt continued. “To them, it’s serious. To us, it’s funny.” Wallace recalled, “Once more I was on the spot.”

Wallace penned the song, a stereotypical “oompah” march that lampooned the Nazi anthem with satirical rhymes. “Ve heil! Heil! Right in der Fuehrer’s face!” it declared in short bursts. The wildly inventive tune portrayed the enemy’s dogma as pure cartoon lunacy, appropriately fitting the cartoon’s working title, “Donald Duck in Nutzi-Land.”

But the song did not have to wait for the film’s release to reach American audiences. In September of 1942, it debuted on record courtesy of RCA Victor and quickly became “the biggest novelty smash since ‘The Music Goes Round and Round,’” according to LIFE magazine. It reportedly made the top five in the popular charts in less than a month. Up-and-coming bandleader Spike Jones recorded an especially popular version that emphasized the so-called “Bronx cheer” between shouts of “Heil!” The colloquial “blowing a raspberry” became a playful act of defiance in the face of Nazi aggression.

LIFE published a photograph of Oliver Wallace performing the irreverent taunt. “The truth is, I didn’t know what Walt would think of the highly robust Bronx cheer,” he reflected in Dispatch from Disney’s. “Could such a sound be used in a Disney picture? ‘Let’s hear it,’ said Walt. I let loose. Walt laughed. The rest is history.

Donald Duck In a Nazi Nightmare

“It was a put-down of Hitler,” director Jack Kinney explained years later to historian Michael Barrier. “It served a […] good purpose, even though it was propaganda…” Kinney worked with writers Joe Grant and Dick Huemer on the short subject’s narrative, but as he pointed out: “The tune carried it.” The simple plotline portrayed Donald Duck—then Disney’s biggest screen star—as a resident of a Nazi state. Forced out of bed at bayonet point, he smuggles a single coffee bean to drink and saws off a piece of hardened bread to eat. The malnourished duck is then hastened off to work at a munitions factory where it becomes impossible to keep up with the rapid assembly line. He eventually spirals into a terrifying montage of fascist iconography, only to wake up in his real bed in his American home, grateful that it was all just a dream.

Writers Grant and Huemer wrote in Dispatch from Disney’s, “We feel that a public character such as Donald Duck, writhing rebelliously in the clutches of the Nazis, will bring the situation home to every man, woman, and child in this country as plainly as though they were witnessing the discomfiture of their own grandmothers.” They hoped Donald could serve the aims of propaganda better than just “another movie actor.” The duck’s penchant for getting into antagonizing situations and stubborn refusal to accept his plights proved an effective vehicle for illustrating the evil of the Axis system.

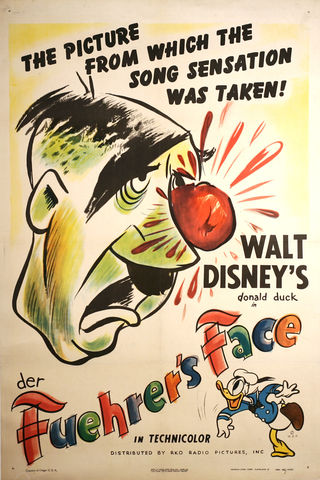

The popularity of the song “Der Fuehrer’s Face” merited the cartoon’s name change to the same title—such was the advantage of capitalizing on the song’s notoriety, even over the name of Donald Duck. The film’s theatrical poster adapted the original artwork drawn for the sheet music by Disney Legend and animator Ward Kimball—a view of Donald throwing a tomato at Hitler’s face—and announced, “The picture from which the song sensation was taken!”

Der Fuehrer’s Face Is A Smashing Success in Theaters

Der Fuehrer's Face began showing in American theaters after Christmas of 1942, the country’s second consecutive winter holiday at war. Multiple newspapers declared the film “greater than the Three Little Pigs (1933),” which had been the standard in Disney short cartoon fare for nearly a decade. That same month, victory seemed near at the battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands—the first American offensive campaign of the war. The battle had been raging for four months between the Japanese and the United States Marine Corps, Army, and Navy. In some American towns, Der Fuehrer’s Face accompanied newsreel and documentary programs reporting on the hard-fought campaign.

By January 1943, increasing numbers of theaters were presenting the cartoon. Since Disney’s films were distributed by RKO Radio Pictures at the time, Der Fuehrer’s Face was often screened with the RKO feature Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942), a Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers drama about escaping from Nazi-occupied Europe. But as the cartoon spread across the country and grew in popularity, it continued to be attached to other films, including another escape story—Casablanca (1942). In March, William Wyler’s Mrs. Miniver (1942) shared Hollywood’s familiar Carthay Circle Theatre with Der Fuehrer’s Face just a week after both films received Oscar® wins at the 15th Academy Awards (Miniver won Best Picture among others).

With award buzz only adding to its momentum, Der Fuehrer's Face “swept the country like a whirlwind,” according to one paper, and was hailed by others as “Walt Disney’s funniest creation,” a “howler,” a “morale-builder,” “hilariously satirical,” and most humorously, “Walt Disney’s private demolition bomb.” “There is little question,” exaggerated one Oregon writer, “that if prints of Der Fuehrer's Face could be dropped over Germany, Herr Adolf would be laughed right out of the country.” Another from Pennsylvania more cogently observed that it was “one of those pictures in which everybody working on it took the greatest pleasure in their [contributions] to its production.”

Disney WWII Propaganda Becomes an Important Part of History

Though Der Fuehrer’s Face ignited a flurry of excitement from American audiences and those from other Allied countries, the cartoon was nonetheless a work of propaganda. Its bold use of caricature and satire had a limit in the face of world war. Writer Dick Huemer wrote in Funnyworld magazine in 1980: “How effective films such as these were in helping to win the war is perhaps open to question, and that puts me in mind of the last two lines of [Robert] Southey’s famous poem [“The Battle of Blenheim”], which is concerned with another world war: “’But what good of it at last?’ / Quoth little Peterkin. / ‘Why that I cannot tell,’ said he, / ‘But ‘twas a famous victory.”

Disney Legend, artist, writer, and producer James Algar commented in 1985, “[...] The hatred expressed in some of that propaganda is kind of shocking, but we have to recall how shocking the times were.” And as columnist Helen Zigmond noted when Der Fuehrer’s Face was first released in December 1942, “It is filled with clever digs and subtle comedy every foot of the reel. Yet—as thoughts of the millions of Jews, Russians, Greeks, tortured, mutilated, starved go through one’s mind—it isn’t comical. The laugh sticks in one’s throat. Brilliant animating cannot make the Nazis funny!”

This article is Part I of a two-part blog article about Der Fuehrer's Face. Part II can be found here.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image credits (in order of appearance):

-

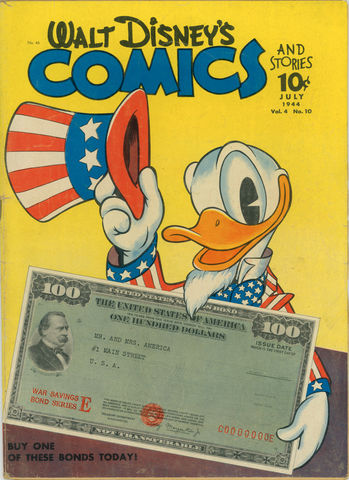

Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, #46, Vol. 4, No. 10, July 1944; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

-

Walt Disney Productions Staff; Dispatch from Disney's, c. 1943; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation © Disney

- Disney Studio Artist; Movie poster for Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.