On November 30, 1955, Walt Disney’s Disneyland television program aired “The Story of the Animated Drawing,” an hour-length exploration of the medium that had made Walt famous. The show presented a documentary of the history of animation—from its ancient origins to its more modern innovations.

The program’s screenplay was penned by Dick Huemer, a long-time Disney story writer and director, whose own animation career stretched back nearly 40 years—even longer than Walt’s—to animation’s first bustling commercial scene in 1910s and 20s New York City. During that time, one of the medium’s dominant artists was renowned cartoonist Winsor McCay.

In some ways, McCay was the forerunner of Walt Disney in terms of American animation. Historian John Canemaker, the preeminent authority on McCay, describes the cartoonist as such, saying, “McCay distinguished his work from that of his contemporaries in the field by the sophistication of his elaborate graphics, the fluid movement of his characters, the attempts to inject personality traits into those characters, and the use of strong narrative continuity.”

Even early on, Walt cherished these same principles when he approached the art form. “Animation can explain whatever the mind of man can conceive,” Walt had said. “This facility makes it the most versatile and explicit means of communication yet devised.” His vision drove him to push the practical and feasible limits of animation into new, innovative territories. But, even before Walt, McCay was among the first artists to push these limits.

Only ten or so years younger than Walt’s father, McCay was born in the late 1860s in Michigan; both the Disneys and McCays of North America originally hailed from Canada; and, much like Walt during his formative years on the Missouri farmstead where he famously drew his neighbor’s stallion, Rupert, young McCay was also a natural artist, once saying, “I just couldn’t stop drawing anything and everything.” McCay was already a household name by the time he moved to New York City and gave animated cartoons a try. He had become America’s preeminent newspaper cartoonist, even working for a time for magnate William Randolph Hearst.

The coming artist will make his reputation not by pictures in still life, but by drawings that are animated.

Though McCay was not the first to make animated films, he was the first to imbue his work with lavish detail and refinement, a standard that, as Canemaker points out, would not be matched until Walt’s films of the 1930s. McCay’s first release was Little Nemo in 1911, which was as an animated adaptation of one of his most popular comic strips—an approach Walt would later “reverse” when he turned his beloved animated characters and shorts into comic strips, which became popular internationally beginning in the 1930s.

Little did he know, in adapting a comic strip to the screen McCay was actually setting a precedent back in 1911 that continues to this day. Of course, there was much less fanfare: McCay’s animated characters, though able to move, looked much like their static, comic strip counterparts, but, instead of being printed in a newspaper, they were projected onto a screen. Additionally, McCay generally worked alone, with a small team of assistants, crafting the thousands of painstaking drawings (all on paper at first). Fearful of compromising the quality of his work, McCay chose not to embrace the industrialized animation workflow that other producers in New York were then developing and insisted upon this more “hands-on” approach.

McCay’s third film, 1914’s Gertie the Dinosaur, is perhaps his most significant. In the aforementioned 1955 television program, “The Story of the Animated Drawing,” Walt says, “Gertie was not presented in the way modern films are shown today. It was part of a vaudeville act in which Winsor McCay appeared on the stage.” Walt’s television program even went to great lengths to dramatically recreate the original vaudeville presentation of the cartoon, in which McCay himself (in this case an actor) would stand beside the screen, circus tamer whip in hand, and interact with the projected, animated dinosaur.

The character of Gertie was also the first great achievement in personality animation. McCay introduces the bashful creature, who gently sways from side-to-side on her massive legs before timidly waving a ‘hello.’ Mayhem then ensues as different kinds of distractions fill the screen; McCay struggles for Gertie’s attention during the chaos, and, later, she dances the “Dinosaur Dip,” rolls over to play dead, and drinks an entire lake dry. For the short’s finale, McCay magically steps into the screen and joins Gertie in her animated world.

In order to create a lovable dinosaur and accomplish these seemingly magical feats, McCay used mathematical precision and groundbreaking techniques, such as the process of inbetweening, which later became a Disney standard. Thanks to all of these elements, Gertie came to life for audiences; she seemed to be thinking on screen. It was a true watershed moment in animation.

Though McCay made a number of additional animated cartoons through early 1921, including the notable The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), he ultimately stopped making films. His intense comic strip workload was part of the reason he stopped, but it is also speculated that he was frustrated with the advancement of the art form, and how it was perceived by fellow artists and audiences alike. “Artists haven’t yet taken animation seriously enough,” McCay said. “When they do, they will make some marvelous pictures.” McCay would continue illustrating until he passed away in 1934 at the age of 62.

By the end of the 1920s, Walt was the dominant presence in American commercial animation, thanks in large part to the debut of Mickey Mouse in Steamboat Willie (1928) as well as the premiere of the Silly Symphony series in 1929. Walt’s real ingenuity lay in his ability to develop an animation process that, over time, was both practical enough to maintain a steady output of short subjects (and eventually feature films), whilst simultaneously achieving those high artistic standards his studio was known to put forth.

Animation can explain whatever the mind of man can conceive. This facility makes it the most versatile and explicit means of communication yet devised.

Just as McCay had foreseen, audiences began to “demand action” in popular art, and artists, such as the Disney animators, had to work “hand-in-hand with science” in order to “evolve a new school of art that… revolutioniz[ed] the entire field.” Of course, Walt did just that. His innovations would not only grow to revolutionize the field of animation, just as McCay had predicted, but Walt would pioneer an entirely new type of animation—one that at least thematically harkened back to Gertie. In 1964, Walt greeted television viewers standing with a trio of Audio-Animatronics® dinosaurs which had been created for that year’s debut at the New York World’s Fair.

Fifty years removed from McCay’s vaudevillian marvel, Gertie, another showman was making ancient beasts move on screen—this time in a full three dimensions. During the broadcast, Walt, who was even sporting a small riding crop not unlike McCay’s circus tamer’s whip, jokingly looked over at one of the three young brontosauruses and said, “You know you’re on television?” Walt saw Audio-Animatronics figures and the technology that brought them to life as an extension of the traditional animated art form, and, in many ways, his Imagineers were exemplars of McCay’s thought that the fusion between art and science would herald new, boundary-breaking forms of artistic expression.

During production of the 1955 Disneyland television show, Winsor McCay’s son, Robert, came to the Studios to act as a consultant for the program. As John Canemaker would report, Walt, greeting Robert McCay in his office, “gestured out the window toward his bustling studio complex and said, ‘Bob, all this should be your father’s.’”

–Lucas O. Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image Sources*:

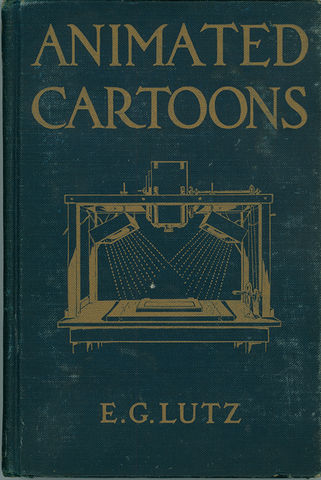

- Lutz, E.G. Animated Cartoons (1920), collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, Gift of Walter E.D. Miller, 2008.3.1

-

Winsor McCay demonstrating Gertie the Dinosaur, 1909; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, 1999.3.1048

-

McCay, Winsor, cel from The Sinking of the Lusitania, 1918; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, 2007.55.1

-

Walt Disney with dinosaurs, “Disneyland Goes to the World Fair” (1964); courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives, Photo Library, © Disney

*Cited in order of appearance