“Do you know what Gremlins are?” asked the national gossip columnist Louella Parsons in October 1942. “They are imaginary little characters who fly with the R. A. F. [Royal Air Force] pilots. They are mischievous little elves who become so real to the R. A. F. boys that they almost live and breathe.” It just so happened, reported Ms. Parsons, that none other than Walt Disney himself was planning to make a film about these little creatures.

Gremlin Lore and Roald Dahl

Though their precise origins remain unclear, the folkloric Gremlins became a topic of fascination during World War II as the personification of technical pitfalls involved with flying an aircraft in combat. When an unexplainable issue occurred, pilots blamed it on a Gremlin—a pesky, gnome-like creature who crawled about an airplane’s surface wreaking havoc.

As air power expanded during World War II, Gremlin stories were favorites among R. A. F. pilots. One such young flier was Roald Dahl, a Welsh-born flight lieutenant with a prolific imagination and keen writing ability. Dahl flew in combat and suffered injuries after a crash landing in the deserts of North Africa. He was later posted to Washington, D.C. as an assistant air attaché for the British Embassy.

Dahl, it seemed, took the fantasy of Gremlin lore—what he and others called “Gremlinology”— quite seriously. After arriving in America, he wrote a short story about the characters and attempted to get it published. “Maybe you don’t know what [Gremlins] are,” Dahl wrote to his mother in June 1942, “but everyone in the R. A. F. does. …It’s really a sort of fairy story...”

As the fantastical creature became a popular curiosity, Dahl told a reporter in Washington that a Gremlin was a “bulbous-bodied little fellow. He has spindly legs in huge-topped suction boots which hold him to the wings; a knobby, round head with stubby horns. He wears a derby hat, a boxy red jacket and corduroy trousers.” Female Gremlins were known as Fifinellas and young, male offspring known as Widgets, “floppy creatures who maneuver around the plane like little bags filled with water,” as Dahl told his mother.

Walt Disney Inquires About the Gremlins by Roald Dahl

The young writer was shocked when he received word that his story had caught the interest of Walt Disney, who inquired about adapting the story into a film. By mid-1942, the Disney Studios was taking on an increasing level of military and government work. Walt was also exploring original war-related projects of his own, and began a collaboration with aviation theorist Alexander P. de Seversky on Victory Through Air Power that summer. As another subject concerning the air forces, the Gremlins story appeared to have strong possibilities.

Dahl agreed to let Disney begin work on a feature film, and later in the year, was requested to visit the Studios for two weeks to provide input. Flying overnight, Dahl arrived in Los Angeles the morning of November 12. Disney story artist James Bodrero picked him up and they drove to the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Roald Dahl and Walt Disney Finally Meet

There was no time to rest as Dahl’s availability was limited, and he was promptly taken to the Disney Studios where he met with Walt. “His room itself is very magnificent,” Dahl wrote to his mother, “with sofas, armchairs, a grand piano, and [his secretary] Dolores [Voght Scott] serving coffee or drinks the whole time.”

Dahl soon met with artists who “were waiting with pencils poised to be told what a Gremlin looked like,” as he described. Dahl’s whirlwind of a first day ended with a party, reportedly arranged by Walt, at which Hollywood celebrities including Charlie Chaplin, Greer Garson, and Spencer Tracy took turns impersonating a Gremlin.

Dahl and the artists kept up a rigorous work schedule. “I wrote and they drew,” Dahl wrote to his mother. Walt wanted an illustrated storybook published ahead of the film’s release, so the initial collaboration involved mapping the book’s plot and layout. “And could they draw,” Dahl noted about his new colleagues. “I’ve never seen anything like it in my life. Walt has gathered together there about 80 artists, any one of whom could be placed amongst the first six drawers of pure line pictures in the world…

Illustrating the Gremlins of Roald Dahl

Artist Bill Justice—who took the lead illustrating the Gremlins—later told historian Jim Korkis that “Roald Dahl was a ruggedly handsome man and a war hero… Once he offered to drive me to a meeting and promptly started down the left side of the street! From then on, I drove!”

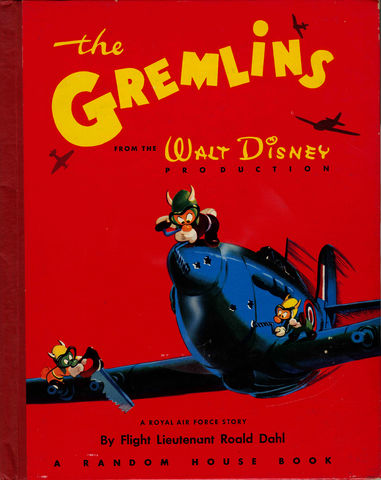

Most of the author’s time in Burbank was spent developing the book—Dahl’s first published work for children—which was ultimately released by Random House the following year. He also consulted with Walt on the feature film story, at that time still planned to combine live-action and animation, perhaps utilizing new photographic processes similar to those soon developed for combination sequences in The Three Caballeros (1945).

Dahl was impressed with Walt and the devotion of his team. Disney referred to his English guest as “Stalky,” a nickname attributed to his tall, lanky build, and—as Dahl confided to his mother—in part derived from Walt’s inability to pronounce “Roald.”

Over the course of his visit, Dahl and the team finished the storybook in rough form. “As soon as I’d finished a page,” he’d write, “it was typed out in the pattern they wanted, sometimes with the type going slantwise across the page and sometimes squiggly. Then they drew pictures all around it, and now and again a full colour picture for the opposite page.”

The trip was, as Dahl told his mother, “the most amazing time.” He left on November 23 with a gift from Walt, autographed copies of the storybooks for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), and Bambi (1942). “I went back to Washington and left them to it,” as he later wrote in his memoir, Lucky Break.

Difficulties With the Gremlins Film

Dahl’s visit was successful, and he and the Disney team continued to discuss the project over correspondence. In addition to the Random House book, Gremlins were seen on military insignias created by the Disney artists. But the Gremlins film ultimately failed to materialize. It resulted in part from the complication that the characters were not an original creation, hindering Disney’s plans to hold copyright. But more importantly, the mischievous Gremlins seemed unable to carry a feature-length story with enough emotional depth.

By 1943, as audiences began to tire of war-related movies, Walt shelved the project. It has since become one of the most famous movies he never made. And like Walt, Roald Dahl would become known for his captivating stories for children and adults alike.

With thanks to Joe Campana and Robert Simpson for their research assistance.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- The Gremlins book cover, 1943; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Walt Disney and Major Roald Dahl sitting with stuffed dolls of Gremlins, 1943; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

- Walt Disney, Mary Blair, Roy Williams and other artists looking at Gremlins artwork, 1942; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.