Before hearing from the people who worked with Eric Larson, learn more about his life and career.

When the time came for Disney’s Animation Department to begin recruiting and mentoring young animators, one of Walt Disney’s “Nine Old Men” and Disney Legend Eric Larson was the obvious choice to lead the program. While no one who worked with Larson ever had a bad word to say about him, one word has been used significantly more than any other when recalling his demeanor: gentle.

Eric Larson as a Natural Leader for Disney’s Nine Old Men

Former Disney animators Kathy Zielinski, Jerry Rees, and Rebecca Rees, and current producer Don Hahn all worked with Larson, and shared some of those experiences with The Walt Disney Family Museum. Rebecca Rees keyed into the core of what it was like to work with Larson, saying, “[Eric] was so kind, so gentle, so nice, and he didn't let me know how much I didn't know.” Jerry Rees echoed this sentiment, recalling, “[He] just had a way of seeing what you were doing, encouraging it, and then reaching in, in a way that wasn't invasive, to support it.”

Additionally, former Disney animator Dale Baer visited The Walt Disney Family Museum in 2018 for the museum’s Nine Old Mentors lecture series. During the program, Baer shared some of his memories from his time with Larson, saying, “You felt drawn to this man. He was just comfortable to be around.”

Larson’s Acts of Kindness

Larson’s kindness wasn’t just limited to the training room. Hahn, for example, experienced this trademark generosity very early on in his Disney career. Back when he had started working at Disney, Hahn, at around 20-years-old, watched Sleeping Beauty (1959) and completely fell in love with the film. After watching it, Hahn sent Larson a note to show his appreciation for the film, and Larson penned a note back, on Sleeping Beauty letterhead, writing, “Don, I’m so glad, it was such a hard movie to make, and I’m glad that it extends over the generations, and I’m glad you appreciate the quality.” When he received this letter from the legendary animator, Hahn said, “I was just floored.”

Others who came into contact with Larson also benefited from these small acts of kindness and deeply personal gestures. In fact, both Rebecca and Jerry Rees experienced this same generosity before either of them worked at The Walt Disney Studios. Rebecca Rees recalled that, as a young person, she wanted to get into character animation. During a portfolio review, Larson started taking out what she considered to be some of her best work. As Larson removed the pieces, Rees asked him why he was doing so; Larson said, “You said you wanted to go into character animation,” and, when she confirmed that was true, Larson went on to say, “Well, [these pieces are] highly rendered. If they see those, they’re going to put you in layout.” Larson, with such generosity, guided Rebecca Rees even before she was reviewed for the hiring process, and she listened to his advice. “They hired me from the sketchbook,” she said. “Just that one sketchbook.”

Jerry Rees’s first experience with Larson occurred when he was just 16 years old, visiting the Studios with his father. Rees brought his portfolio, which was “portrait work, and…super-8 animation and some of [his] flipping scenes,” and Ed Hansen, administrator of the animation training program, took him to see Larson. Of course, Rees was still in high school, so, as he recalls, Larson said, “Well, you know, we got an extra desk over here, so when you get breaks from high school, if you want to come in, you can use this desk and I'll give you some pointers and stuff.”

The Talent of Disney’s Nine Old Men

When it came to talent, all of Disney's Nine Old Men were more than qualified to teach a master-class in animation. When it came to mentoring, however, Larson was by far the most capable. As Baer said during his lecture, he was truly a “very kind and very patient mentor,” especially for an artist who was getting their feet wet. That is, for a new artist working at the most successful animation studio of all time, the experience could become very daunting very fast, but Larson’s tutelage went beyond simply teaching young artists how to hold a pencil—he made them comfortable, with themselves and their skills. Zielinski reiterated this, saying, “I genuinely feel he enjoyed being there around the students and the new hires and passing his knowledge on to us.” Not only did Larson have this gentle, patient, and personable temperament, but, as Jerry described, he was like the “mother hen,” and he had “the skills and that whole entire archive of history” to share. For Hahn and his fellow artists, Larson was “really the heart and soul of the place.”

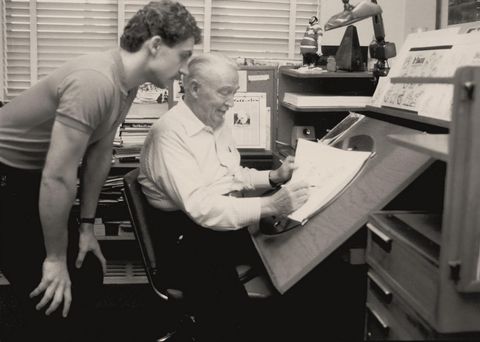

In his book The Nine Old Men: Lessons, Techniques, and Inspiration from Disney's Great Animators, published by Taylor & Francis, former Larson trainee Andreas Deja lauded Larson’s efforts in, and importance to, animation. “Eric Larson’s final contribution to the art of animation was enormous,” Deja declared. “He made sure that a new generation of animators saw the significance, the potential, and the challenge of Disney personality animation. Without his important involvement as a teacher and motivator, the film medium that Walt Disney had pioneered for many decades would have died in the 1970s.”

Jerry Rees knew all too well about Larson’s significance. He recalled the difficult time at the Studios when Larson was removed as director from the animated short The Small One (1978) and replaced by up-and-coming animator Don Bluth. “I have a feeling that if Eric had stayed and done that, I'll bet you Brad [Bird] and Rebecca [Rees] and me, and maybe Henry Selick and who knows…a bunch of people probably would have stayed at the Studios,” Jerry said. “But all of us left for a few years, and then found orbits back in different ways. But yeah, that whole next year probably would have been different if Eric had kept training as director on a featurette to…take us all to the next step.”

The Preservation of Walt Disney’s Legacy

Perhaps the only thing Larson was better known for than his warmth was his passion for preserving Walt’s legacy. In John Canemaker’s book Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men & The Art of Animation, published by Disney Editions, former Larson pupil John Pomeroy recalled, “Eric was more comfortable with handing on the baton than any other of the Nine Old Men. While the remainder of the giants here still were furthering their careers, Eric saw a need to pass on this language and this knowledge.” During the Nine Old Mentors lecture, Baer reiterated this point, saying, “[Larson] was very loyal to the Studios and Walt’s way of thinking, probably more than anybody.”

In passing on what Hahn called “the ethics and aesthetics of Walt Disney,” Larson made certain that the Studios would carry on the legacy that Walt and the Nine Old Men had fostered for decades—the legacy that audiences grew to know and treasure. In his memoir, Larson stated, “[Walt] left a wonderful heritage. We would indeed be negligent and unappreciative if we failed to put forth every effort to pass it on to others.” And in his never-ending effort to preserve Walt’s legacy, Larson undeniably left one of his own, too.

–Keith Gluck, blog contributor

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

-

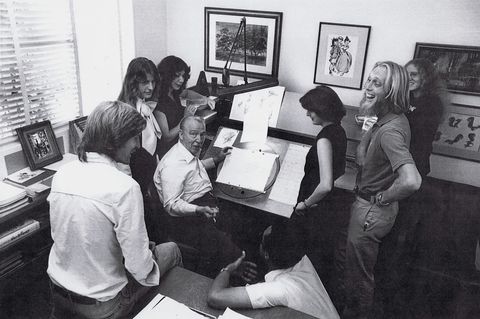

Eric Larson surrounded by animation trainees Lorna Pomeroy Cook, Heidi Guedel, Bill Kroyer, Dan Haskett, Emily Jiuliano, Henry Selick, and Becky Canfield; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

-

Andreas Deja with Eric Larson at animator's desk; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney