Often lost in the public perception of Walt Disney’s personality is his wicked sense of humor. He has frequently been characterized as simply a lowbrow, fond of barnyard humor and gags involving the rear end. Although Walt admitted, “I can’t laugh at intellectual humor, you know? I want to be hit here. I’m just corny enough. I want to be hit right here in the heart,” the comic artifacts of his Midwest upbringing are only a single component of a puckishness that was far more complex—and often surprising to his colleagues and employees.

Often lost in the public perception of Walt Disney’s personality is his wicked sense of humor. He has frequently been characterized as simply a lowbrow, fond of barnyard humor and gags involving the rear end. Although Walt admitted, “I can’t laugh at intellectual humor, you know? I want to be hit here. I’m just corny enough. I want to be hit right here in the heart,” the comic artifacts of his Midwest upbringing are only a single component of a puckishness that was far more complex—and often surprising to his colleagues and employees.

Walt exhibited a sly sense of humor as a youth. “I was always buying these trick things,” he recalled, “and I came home one time with this old plate lifter. You’ve seen it, it’s a bladder you put under the tablecloth, and you run it, a bulb around, you see? And I showed it to mother. She got a big kick out and she says, ‘Let me pull that on your father!’

“We were all sitting there, and every time my dad would go down to get a spoonful of soup, my mother would rock the plate, and it was a funny thing. My dad didn’t notice it. My mother was just killing herself laughing. So she kept on doing this, and finally my dad would say ‘Flora what is wrong with you? Flora, I’ve never see you so silly.’…my mother had to get up and go lay down in the bedroom she was laughing so hard. My Dad never caught on!”

Walt was remembered for dressing in costume in order to startle his young cousins, and on one well-known occasion, Flora answered her front door to find a young woman who began to ask her all manner of silly questions. The puzzled Flora soon noticed that the visitor was wearing one of Flora’s own best dresses. Young Walt had even borrowed a wig and put on make-up to complete his illusion, and “sell” his “gag.”

As Walt became a studio head, his sense of humor informed the work his staff created, and his ability to find funny situations (and find situations funny) was well-regarded throughout his career. "He was the consummate gag man," Walt's daughter Diane Disney Miller recalls, "and proud of it." Walt's appreciation of humor also shaped a creative environment at work, where humor, playfulness, and practical jokes were all a part of the daily routine.

In his book The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life, Steven Watts reports, “According to a host of Disney employees, a constant round of horseplay, gags, and practical jokes punctuated the demanding routine. Goldfish mysteriously appeared in water coolers, stressed-out animators engaged in pushpin-throwing contests, story meetings turned into impromptu comedy shows, and Limburger cheese placed on the light bulbs under an animator’s desk melted and ran to the floor, to the great hilarity of all present. Walt consistently looked the other way, viewing such shenanigans as both a useful way to blow off steam in a highly stressful situation and a kind of psychological lubricant for the creative process.”

In his book The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life, Steven Watts reports, “According to a host of Disney employees, a constant round of horseplay, gags, and practical jokes punctuated the demanding routine. Goldfish mysteriously appeared in water coolers, stressed-out animators engaged in pushpin-throwing contests, story meetings turned into impromptu comedy shows, and Limburger cheese placed on the light bulbs under an animator’s desk melted and ran to the floor, to the great hilarity of all present. Walt consistently looked the other way, viewing such shenanigans as both a useful way to blow off steam in a highly stressful situation and a kind of psychological lubricant for the creative process.”

Comic strip artist Floyd Gottfredson famously related the story of an elaborate practical joke in their department between Al Taliaferro and Ted Thwaites. Ted brought in a small can of fruit cocktail every day. He loved it so much, that Al simply couldn’t resist. He brought in a can the same size—but a can of mixed vegetables—and switched the labels. This went on for days, with Ted baffled at his beloved fruit cocktail can perpetually yielding green beans, peas or carrots, and even hominy. The gag continued until the day that Ted picked up his “fruit cocktail” can and the label, still wet with rubber cement, slipped off.

“When you’re in animation, you grow up with cartoonists,” former animator and Imagineer Rolly Crump says, “and the gags that cartoonists played on each other went clear back to the ‘30s. Walt allowed this—in fact, he thought, any of the gags that the guys came up with, we’d do!

“One evening while I was working on Peter Pan, I came in and there were two guys on their hands and knees, and they were drilling a hole in the wall…and this is on overtime,” Crump remembers.

The two pranksters lined up the hole in the wall with the electrical cord access hole under the animation desk in the next room, which happened to be animator Milt Kahl’s. They ran a hose attached to a big squeeze bulb, and would pop talcum powder onto the unsuspecting artist’s crotch. “So he would get up to go to the bathroom and ‘Geez! What’s all this?’ There’s talcum powder all over his crotch,” Crump says.

“One weekend, they collected flies. They had a big funnel and they had jars of flies. They kept tapping this jar of flies and the flies would keep coming up from underneath the desk and he’s yelling and screaming about the flies.”

Crump was not merely an observer in the act of practical jokes, though. “I could go on forever about the gags that we played,” Crump smiles.

Crump and “Illusioneer” Yale Gracey were engaged in testing terrifying illusions for The Haunted Mansion, and had a large workspace with controlled lighting and all the windows blacked out. “We had skulls and skeletons and we had stuff all around the room…gory heads…a great big monster that we painted with all kinds of things on it, and a weird head. My wife made a China silk ghost that you’d put over a small caged fan and when you turned it on, the ghost would fill up and start…we had all of this stuff.”

One day Crump and Gracey got a call from the Personnel Department—the startled janitors had requested that they leave a light on in their workshop of frightening effects. Naturally, the two could not resist this temptation.

“Right in the middle of the room, we had an infrared beam,” Crump says. “When you first came in the lights were kinda low…but when you broke the beam, the black lights came on, the real lights went off, the monster blew up, and up comes the ghost.”

When the pair came to work the next day, the ghost was fluttering, the monster head was hanging in the center of the room, and right in the middle of the floor was an abandoned broom.

When the pair came to work the next day, the ghost was fluttering, the monster head was hanging in the center of the room, and right in the middle of the floor was an abandoned broom.

“We get a call from the Personnel Department,” Crump chuckles. “They are NEVER coming back."

“No matter what you were doing, there was this little craziness that kind of stayed with you when you were doing stuff,” Crump says.

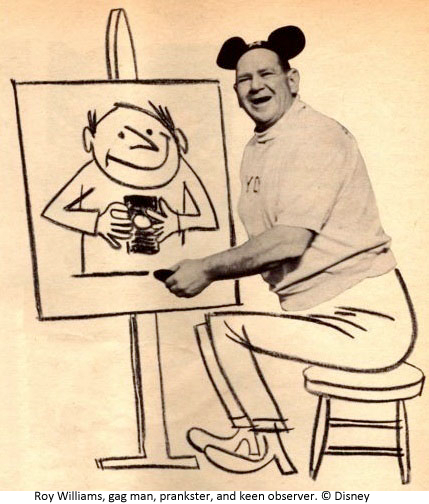

Other jokesters around the Studio were subtler in their approach. Roy Williams, story artist and “gag” man extraordinaire, best known as “The Big Mooseketeer” of the TV hit “The Mickey Mouse Club,” manifested his jokes as visual commentaries.

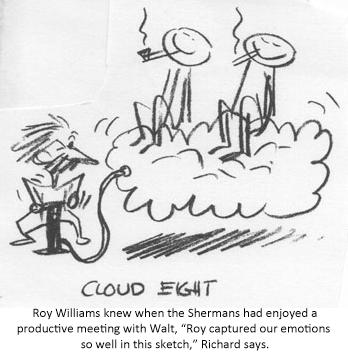

Composers Richard and Robert Sherman occupied the office next door to Williams, and in exchange for their constant musical accompaniment, the boys were frequently greeted with the flutter of a sheet of paper from Williams under their adjoining door.

“Roy was contributing his running commentary to what he saw, heard, or imagined was going on next door,” Richard Sherman says, the artist creating a funny visual reaction or commentary to a “soundtrack without a picture” from the adjacent office.

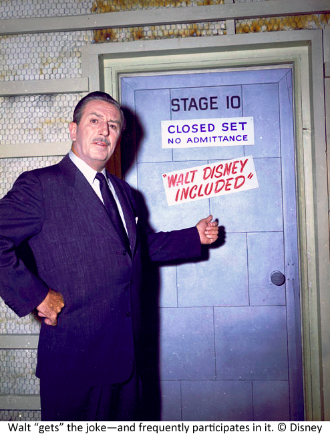

One key reason that such a lunatic and freewheeling environment continued to flourish at Disney over decades was simple enough: Walt got the joke.

One key reason that such a lunatic and freewheeling environment continued to flourish at Disney over decades was simple enough: Walt got the joke.

While Crump was at work with WED on the World’s Fair, colleague Blaine Gibson, the head sculptor, had created a very powerful “cave woman.” After being figure-finished, painted, and dressed in raccoon fur, she was being assessed by Gibson. He asked Crump to take his shirt off and have a few Polaroid pictures taken next to the figure, to see if the color values of the skin matched. Crump went one better, took of his shirt, rolled up his pant legs, and proceeded to enact some rather amorous poses with the hefty cave woman.

“I basically attacked this woman,” Crump laughs, “and we had eight or ten of these black-and-white Polaroids…and Blaine put them in this little file.”

All but forgotten a few weeks later, Walt was meeting with Gibson, and the sculptor pulled out the file in order to retrieve some reference, with Walt looking over his shoulder. Walt’s eyebrows shot up as he saw a series of passionate encounters between Crump and a prehistoric paramour. Walt looked carefully through the provocative portfolio, and simply and openly burst out laughing.

Legendary Disney animator Ollie Johnston recalled, “Walt was keenly aware of the creative process and didn’t criticize anyone for taking time off to do gags. He seemed to be aware that we were sharpening our skills. The only thing he used to say was, ‘Why don’t you get some of that in the pictures?’”