Roy Disney was a keen observer and judge of character. He was a good listener. His ability to size up people and use his imagination to think from their perspective made him a good negotiator. He sometimes acted as an advance man for Walt who was immersed in production details, storylines, and almost everything else at the Studios. Roy kept Walt abreast of developments in succinct, vivid letters and memos.

For example, in anticipation of the production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, when a need for experienced animators arose, Roy met with individuals in New York and reported back to Walt. In a letter from May of 1933, Roy describes Vladimir (Bill) Tytla after taking him to dinner. “He is at Terry Tunes now and seems to feel that he is one of the ‘king pins’ there and that they need him badly, so that he evidently is not in the mood to leave unless he was tempted away by an attractive offer.” Roy, however, was “merely taking the attitude of getting acquainted in case in the future he might possibly be interested in coming out with us.” He sums up Tytla as “a nice fellow, rather a Rudy Ising type for looks. He is a mixture of Polish and Russian; left the United States in 1929 just as sound was breaking, to go to Europe to ‘travel and study painting and sculpturing’; stayed over there about a year and a half. He expresses a keen desire to have the opportunity to do ‘better work.’ He follows all of your product closely, it seems, as he had a good knowledge of all the Symphonies and a number of the Mickeys.” Animator Ising’s history with the Disneys and with another Disney animator, Hugh Harman, is well known to animation lovers. In fact, Harman envied Walt Disney because “he had Roy paving the way for him all the way.” It’s telling that Roy refers to the Studios’ shorts as “your product,” leaving himself out. It reflects his motivation for renaming the company and throughout a long career. He was Walt’s champion. Tytla joined Disney’s late in 1934.

After World War II, Walt produced features that were packages of short subjects, with some combining live-action and animation, including Song of the South (1946) and So Dear to My Heart (1949). Profits stranded in the U.K. because of the war led Walt to develop projects there, starting with Treasure Island (1950). Roy went to England, seeking the rights to the Winnie the Pooh stories. Even during wartime, Roy met P.L. Travers in New York to talk about rights to her Mary Poppins books. Travers comes to life in Roy’s memo to Walt, dated Jan 24, 1944, which forecasts her working relationship with Walt and the Studios, nearly 20 years later. Following are excerpts from the memo:

“We had a very nice talk, and she seemed glad to see me. She said in years back she was a contributor to several English magazines, and on a couple of occasions had written about Walt Disney pictures. I told her quite frankly that I had nothing to discuss except the fact that you were intrigued with Mary Poppins, and felt that if she was interested, you would like to consider (and have her consider) the possibility of working with us on the writing end of a screen adaptation. This, she said, she would be very glad to do, but I didn’t attempt to talk money with her at all. I told her now, it was only an idea, and that was my reason for coming to her first.

“She owns the copyrights, but said by her contract with Reynal and Hitchcock, her publisher, they have an interest in what she does in motion pictures. I had a hunch this was a ‘stall’ at the moment, for the way she said it, it didn’t sound logical to me. It seemed to me that she was fencing, unless, perhaps she has appointed them as her agents. […]

“Mrs. Travers said she could not conceive of Mary Poppins as a cartoon character. I tried to tell her this was a matter that should be left for future study—that it might be best for Mary Poppins to be produced in a combination of live action and cartoon, using the animation to get the fantasy and illusion of the Mary Poppins character. I told her that we were thoroughly qualified and equipped to produce either medium, and, as a matter of fact are producing such type of picture….

“Summing it up; she is a woman about forty-five or forty-eight years of age, sort of an Amelia Earhardt [sic] type of person, with an English accent. She was very flattered over your interest—on the other hand, quite cagey in her talk. She seems like a very intelligent person, and I think the best way to follow this up is for you to call her on the phone sometime and have a conversation with her….”

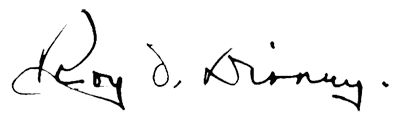

He signs the memo with a rounded flourish: “Roy.” The R billows out like a sail over the long-tailed Y’s boat. The definitive period follows his signature often.

A few years earlier, Roy had sent a memo to Walt about Major Alexander de Seversky, the author of Victory Through Air Power. De Seversky and representatives from RKO, Disney’s film distributor at the time, had lunch with Roy. The memo is dated July 21, 1942. Disney’s feature was released the following year. In this excerpt, Roy prepares Walt as de Seversky is about to sign his contract.

“I want to give you my reaction to Seversky before you meet him at the studio. I was very pleased with his manner and attitude, and after over an hour of general conversation, mainly on the subject of his hobby now-a-days, that is air power, I felt that he would be quite a safe fellow for you to talk to and quite refreshing and interesting.

“He didn’t talk like one that would try to move in and arbitrarily have his way, or try to influence you in making the picture. Everything he said seems to point to his desire to be constructively helpful. He realizes, probably even better than we do, the great differences of opinion and the difficult political situation around the entire subject matter.

“I am sure he could give you a lot of ideas that will be helpful. I am sure, also, that he hasn’t anything in his mind except his desire to be helpful and that he has no idea of trying to dicker for the use of his services at some additional price. I got the impression that he is sincerely crusading, that he would be very much happier in actual airplane production, but that he feels somebody must do this crusading. He has gone so far with it now he says he is in a spot where it would be hard to let go even if he wanted to…..

“If he is the sort that proves troublesome and hard to get along with, he is a very disarming sort. He seems in fact, like a very sincere and reasonable person. My impression of him was very good. As I say, I think you definitely should invite him out to the studio and have a talk with him over the story boards.”

De Seversky’s “crusading,” a free publicity campaign, could only brighten their working relationship. Roy was not shy about offering Walt his analysis of a story as well as talented people. This is evident in a handwritten letter sent a few days before the previous example. They were contemplating a Gremlins short subject to accompany Victory Through Air Power. Roy wrote on stationery of The Waldorf-Astoria, where he liked to stay when in New York on business, on July 18, 1942. This is likely in response to a letter Sidney Bernstein of British Information Services wrote to Walt on July 1, 1942, introducing the story by a Royal Air Force pilot (Roald Dahl), without referring to the characters as “gremlins.” Roy opens with:

“I’ve read and thought over the story Gremlin-Lore. My reaction is that the idea is too new and almost subtle for the general public to grasp—and may find little sympathy with a public who don’t fly and therefore would not react to the lore as such, and that its main value is only to story value. As for the story value itself, it doesn’t strike me as a strong story idea (although I realize this might only be the basis of an idea as you think of it.)

“Further—to include this as a subject to be grouped with V. Thru Air Power, isn’t it pouring too much Air Material in one group. [sic]

“To me the author fails to give a feeling of logic & reason to the Gremlin’s [sic] existence or their actions and as a consequence to me it lacks a sincerity. This I suppose could be corrected and an “Editor’s note” on the “Lore” as a fiction among flying men, could be planted.

“Still, it don’t [sic] appeal to me as a strong material idea to be part of an important feature length venture….

“We could as suggested illustrate a magazine story as part consideration—then use the illustrations in a book—”

Roy’s argument may have swayed Walt. The Studios illustrated a magazine article (Dahl writing under the alias “Pegasus”) and a book (attributed to Flight Lieutenant Roald Dahl) about these aircraft discombobulators. But as it turned out the property went no further, exactly as Roy suggests, even though Studios’ staff developed art and storyboards toward a film version and the book cover refers to the film. The “editor’s note” may have inspired the book cover tag line “A Royal Air Force Story.”

Here’s a casting suggestion for Old Yeller. In a memo to Walt dated December 14, 1956, Roy writes:

“For what it’s worth, I have a comment to make about the two dogs used in the tests.

“The Labrador showed a tendency to be cowed or timid—but on further thought it struck me that in the story OLD YELLER was always sneaking around, stealing food and eggs, and that disposition seems to tie in with the tendency in the Labrador’s nature more than with the nature of the St. Bernard. In other words, the Labrador acted as though he could be sneaky and steal eggs and meat, whereas a sneaky, stealing disposition did not seem to go with the other dog.

Just a thought.

R.O.D.”

Old Yeller was played by Spike, a “‘refugee’ from the Van Nuys Animal Shelter,” according to a press release. He looks at least part Labrador.

Even the way Roy gave his brother a gift shows his protective, advisory spirit. He didn’t just hand it to him. The thoroughness and sense of fun reflected in a memo from June 29, 1950, echoes the business attitude of the Studios in general. Cinderella had been released months earlier, so the company was in financial euphoria for the first time since the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937. Roy had the Studios’ staff test the gadget (a Minox camera), including Roy [likely Roy E. Disney]; Earl Colgrove, supervisor of the Still Camera department; and Jack Cutting, an early assistant director then working in foreign relations. Roy’s memo to Walt reads:

“Here is a camera that I bought in Francfort, Germany, [sic] for you. I thought you might like it.

“It is an outgrowth of the spy cameras of the war. The Morgan Camera Company on Sunset, near Vine, handles them here and develops and prints the stock. I am enclosing five rolls of stock. Each contains two cartridges of 50 exposures each. It shoots on 9mm film and is very easy to load. You can see the exposed film in the untaped can. That little roll represents 150 exposures. The beaded chain on the camera is a measuring device for close shooting, such as stealing a copy of a letter from somebody’s desk quickly. The informative and instructional booklets, in English, in the envelope tell all about it.

“The pictures in the envelope you can send back to me when you are finished with them. I just wanted you to have an idea of what could be done it [sic]—not that this is sample [sic]. I shot some in Paris, Jack Cutting shot some, Roy shot quite a number in New York, and then Earl Colgrove shot some around the studio. Earl developed and printed all this stuff here at the studio.

“That’s about all there is to say about it. You will find out the rest when you fool around with it. As I say, I just thought you would be intrigued with the little thing, and would like it.

Anyway, you can be a Junior ‘G’ man now!

—Roy. [signed]”

Conversely, Walt Disney spoke up about financial matters. In one case, he copied Roy on a memo to an employee who authorized the use of the song “Wringle Wrangle,” from Westward Ho the Wagons!, for a commercial for Reingold beer. From 1957, Walt writes [all punctuation is his]:

“In the first place, I don’t think that any of our music should be used for jingles, but above all, definitely not to exploit beer, cigarettes, or such things. We should always be careful about what our music is used for because of our broad audience and also the timeless value of our films.

“In the past we have turned down several of these things, and this should be a continuing policy.

“What’s happening…..isn’t the money coming in fast enough?......Or as they say, ‘Pig, don’t make a hog of yourself!’”

Jennifer Hendrickson has worked for the Walt Disney Archives and in a former research office of The Walt Disney Family Museum. In Boston, she researched and wrote some scripts on musical topics for WGBH Public Radio.

Acknowledgements: Gratitude to Rebecca Cline, David R. Smith, Steven Vagnini, Kevin M. Kern, Michael Buckhoff, Jenn Berger, and Jeff Golden of the Walt Disney Archives for their generous assistance and expertise. Thanks also to Brianne Bertolaccini of The Walt Disney Family Museum, to Margaret Adamic of The Walt Disney Company, and to Paula Sigman Lowery.

Sources

David R. Smith, “Disney Before Burbank: The Kingswell and Hyperion Studios,” Funnyworld #20, Summer 1979, p. 34.

Marty Sklar interview with Bob Thomas, audio, Sep 1, 1995, 11 minutes in.

Roy Disney letter to Walt Disney, May 26, 1933.

Hugh Harman interview with Michael Barrier, 1973, posted Jan 10, 2006, to http://www.michaelbarrier.com/Interviews/Harman/interview_hugh_harman.htm.

Roy Disney memo to Walt Disney, Sep 25, 1946.