“There is a nice philosophy in Cinderella’s attitude. She can teach the young – and others – how to take adversity.” – film critic Helen Bower, April 1950

A Fairy Tale Worth Waiting For

Cinderella (1950) was one of Walt Disney’s most highly-anticipated films. Not since Bambi (1942) had he released a feature-length animated story. After World War II, audiences were impatient for something reminiscent of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), a film that had rescued their hearts from the Great Depression.

“It was the audience that wanted a full-length feature like Cinderella,” animator Frank Thomas remembered to historian Christian Renaut. “Walt would meet people outside, critics, and so on, and people said: ‘Why don’t you do something like Snow White?’ We had Cinderella in the backs of our minds for a long time.” The film at last made its debut in 1950 and the country went abuzz.

Ilene Woods as Disney’s Cinderella

In March 1948, 19-year-old actress Ilene Woods was heard on national radio—where she’d first appeared at age 11—announcing that she would voice Cinderella in Disney’s forthcoming film. “Now I know dreams do come true,” Woods proclaimed before singing “When You Wish Upon a Star.” Months later, Hollywood columnist Louella Parsons reported that according to Walt Disney, Woods “will surprise everyone in Cinderella, she’s that good.”

In January 1950, after two years of cash-strapped production at the Disney Studios, public expectations were growing stronger by the day. The film’s staple of songs, already being previewed ahead of its March release, was garnering acclaim—singer Perry Como had released two sides in late 1949.

February 13 marked Cinderella’s “world preview” at “The Cinderella Ball” in New York City, an event to raise funds for the New York Heart Association, and where Ilene Woods was crowned “Queen,” something her character had not achieved at her own Ball. New York’s Daily News called it “a glittering affair,” placing Walt Disney “in a class by himself… His idealization of the classic love story arrives on the screen with such infinite tenderness that it takes your breath away.”

American readers soon picked up the latest Newsweek with a cover story on Cinderella. “For a long time,” Walt Disney explained, “I have been trying to build an organization. After years I have it. Now it’s a matter of running it. In the old days I did everything – story, animating, cutting, even developing sometimes…Now it becomes a process of feeding the organization. They’re ready to turn it out if you give them the stuff.”

Cinderella Was An Economic Gamble—And It Worked

Walt was gambling on Cinderella to revive the Studios’ economic footing after a debilitating, war-ravaged decade. “Hollywood, where financial candor is often supposed to be as rare as charity, guessed that Walt Disney could use a hit,” Newsweek commented, adding, “Was the Bank of America, [Walt’s] longtime creditor, after all these years still into him for $600,000?” After viewing Cinderella, they concluded, “Not since Snow White or Dumbo was Disney potentially riding so esthetically[sic.] or financially high.”

On February 22, Bing Crosby—who was heard in The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad the year before—promoted Cinderella on his CBS radio program. The crooner sang “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” and welcomed the Firehouse Five Plus Two jazz band as guests—their membership included Disney artists who had worked on Cinderella. “Say Bing, did you mention that full-length Technicolor picture, Cinderella?” asked animator and trombonist Ward Kimball. “We had to play hooky [from work] today. I figured that would soften Walt up.”

The Release and Public Response to Cinderella

On the film’s release day, New York’s Mayfair Theatre opened early, and 200 people lined up beforehand—though children had a school holiday, the crowd was mostly adults. Within weeks, Cinderella was already approaching local box office records and competing for top grosses with live-action counterparts. Film executives across the industry reportedly fretted over a “sinking spell” and concerns that moviegoing was becoming “increasingly less routine.” Maybe an animated feature was just what a sagging audience needed, but regardless, it looked like Walt’s gamble would pay off.

One reviewer called the film “Disney’s first all-out devotion to romantic human love – a revel of intermingled fantasy and warm earthy reality…” Many were happy to see Disney return to fairy tales. “It may be natural for the inquiring Disney to experiment with other types of pictures,” wrote a Detroit critic, “but from Fantasia to Song of the South none has been so wholly delightful as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs – and now Cinderella.” Others compared the mouse Gus Gus to Dopey in their mutual appeal.

Not everyone, however, thought Walt had matched Snow White. In his 1950 book, The Great Audience, critic Gilbert Seldes wrote that Cinderella was “an affirmation of an old faith but without the miracle the old faith had worked.” He mourned the loss of 1930s folkloric charm, replaced instead by “sentimentality.” But Cinderella was not a Depression-era fairy tale like its predecessor. It exhibited its own modernity, with Mary Blair’s visual stylization, Cinderella’s modest sophistication, and a pop-infused soundtrack. Walt’s brilliance was to envision something new and not rehash past success.

Cinderella likely made the best impression with its music, which received Academy Award® nominations for “Best Song” (“Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo”), and “Best Scoring of a Musical Picture.” (Interestingly, “A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes” had performed better on radio than “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo.”) As Boxoffice noted, “The music, an outstanding asset, contributes to the film’s vast overall exploitability, and such ultimate in entertainment values and tremendous merchandising possibilities add up to stratospheric potential.” At a time before Disneyland and its steady income flow, Cinderella’s financial gains were essential

The Impact of Disney’s Cinderella

In August, Canadian audiences in Montreal enjoyed Cinderella’s return to local theaters, the result of “overwhelming public demand.” That same month, a Variety advertisement boasted “You bet it’s a Walt Disney year!” In addition to Cinderella, Disney released Treasure Island, In Beaver Valley, over a dozen cartoon shorts, and its first television special, One Hour in Wonderland—all in 1950. The continuation of this bustling activity was thanks in no small part to Cinderella finally earning between seven and eight million dollars at the box office —its production costs ran just over two million.

Some years later, Walt told journalist Pete Martin that Cinderella was the film that “hit big,” explaining, “I want to be hit right here in the heart…You pulled for Cinderella. You felt for Cinderella.” The lesson of successes like Cinderella and Snow White was that “with any laugh there must be a tear somewhere.”

With thanks to Didier Ghez for his research assistance.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Ilene Woods singing, Cinderella (1950), February 15, 1950; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

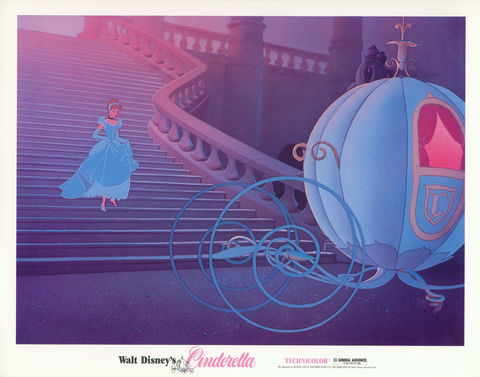

- Cinderella (1950) lobby card, c. 1950; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Mary Blair, concept art, Cinderella (1950); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.