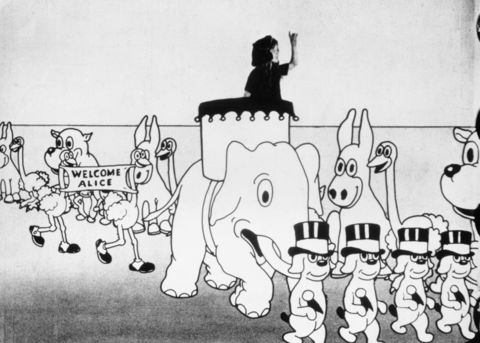

Alice’s Wonderland—the last film Walt Disney made in Kansas City, Missouri—depicts the animated adventures of a true-to-life young girl in a make-believe world. In the original 1923 short film, Alice arrives by train in “Cartoonland.” A large welcoming committee of animated animal characters greets her with excitement and adoration.

Walt’s subsequent arrival in Hollywood, also by train, was a bit humbler. He was 21 years old, and as he himself put it, a failure. Washed up in Missouri, perhaps the west could provide a new start. He was “fed up with cartoons,” as he’d later say, and for a time explored directing and acting in the live-action industry. No one would hire him.

Alice’s Wonderland was tucked away in his suitcase when he stepped off the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad in August 1923. Self-starting in animation seemed the most pragmatic option. But if so, he insisted on improving his craft. In his earliest letter to New York cartoon distributor Margaret Winkler proposing a series of Alice-themed films, he described his will to “inject quality humor, photography, and detail into these comedies.”

For a brief time that summer, Walt also considered reviving his newsreel-style cartoons—similar to the early Newman Laugh-O-grams—in a pitch to theater owner Alexander Pantages. The proprietor liked the idea and asked for a sample reel, but Walt’s new contractual agreement with Winkler changed his priorities. He never sent a sample to Pantages. (The theater’s famed marquee would herald the premiere of multiple Disney features in years to come.)

In 1921, Walt was creating topical lightning sketches and brief animated segments on local news in Kansas City. But by the mid-1920s, audience demand was leaning in favor of “films with continuing heroes” as historian Donald Crafton put it. The 20s saw animation move away from novelty and journalistic illustration to full-fledged narrative storytelling and continuing series.

Young actress Virginia Davis and her family would relocate from Kansas City. Walt’s older brother Roy, recuperating from tuberculosis at a local Navy hospital, became Walt’s business partner. Their uncle Robert Disney was a benefactor and landlord for a time. The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio was informally born in his garage. Uncle Robert’s German Shepherd, Peggy, even became an audience favorite in live-action sequences of the Alice Comedies.

At first, Walt’s production team was smaller than it had been in Kansas City. Roy Disney was taught to hand-crank the movie camera, an all-too-important task as Winkler had demanded better picture quality than in Alice’s Wonderland. Walt directed the live-action and single-handedly created the animated drawings. Two hires—Kathleen Dollard and Ann Loomis—were the studio’s first ink and paint artists. Walt would slowly begin recruiting his old Kansas City friends to join him.

The first new film—Alice’s Day at Sea—was delivered in December 1923. No one else in Hollywood was making animated cartoons. Out of the Inkwell, a New York-based series produced by the Fleischer brothers (and distributed for a time by Margaret Winkler), often incorporated the animated Koko the Clown within a live-action space. Walt had reversed the idea. Each film depicted Alice as a photo-real tourist in a new animated world.

Walt’s Alice Comedies make frequent use of animated text to exaggerate action—“Ouch!” and “Boom!”—which was a signature of Walt’s style going back to his first Laugh-O-grams. Traditional intertitles were less common.

Walt continued to develop his use of animals, characters which “everybody loved,” as he’d say. Alice was often set against a series of funny antagonists. “Inject as much humor as you possibly can,” Winkler wrote to the Disneys.

The Alice Comedies remain equally rewarding for their use of live-action which served as bookends to the animated sequences.

Early on, Virginia Davis is effervescent and wonderfully genuine onscreen. She is the obvious star amidst the clamor of additional young children who appeared as supporting cast and extras, and to whom the Disneys paid token fees. Walt’s voice must have echoed behind the camera (remember, there’s no sound to consider), pleading with his young talent to move this way or emote that way.

The local Silverlake neighborhood of the mid-1920s comes to life in these children, and one imagines an off-camera series of youthful escapades somewhere between a Norman Rockwell painting and a Mark Twain adventure.

By 1924, Walt wasn’t just busy producing his cartoon output, but courting one of the studio’s new hires— ink and paint artist Lillian Bounds. The Idaho native was merely a “visitor” to Hollywood and was connected to the job via her sister Hazel’s friendship with Kathleen Dollard. Walt usually drove both Kathleen and Lillian home each evening, but as Lillian enjoyed recounting, he took Kathleen home first.

With each new animated release— which took Alice on adventures in the African wilds, a haunted house, the wild west, and beyond—Walt’s learning curve rose sharply. The intensive delivery schedule gave him little choice. Films were completed on a monthly basis, the first premiering March 1, 1924. That May, a national critic proclaimed that the Alice character “will make a hit with almost any audience.”

By late 1924, the Comedies were playing all across the United States, often billed as “a Walt Disney Comic.” In October, Alice Gets in Dutch screened at New York’s Piccadilly Theatre on Broadway. The series played back home in Missouri too. A local theater in Shelbyville even featured an Alice cartoon for a school fundraiser screening.

The old gang from Kansas City was beginning to arrive. Brothers Hugh and Walker Harman, Rudy Ising, and Ub Iwerks joined the Alice Comedies crew, now based in a front-office space on Kingswell Avenue. It was a relief for Walt who had been shouldering most of the creative demands. Iwerks in particular enhanced the quality—both artistic and technical—of the Comedies.

In March 1925, Alice Cans the Cannibals—one of the last Virginia Davis films—was attached to a multi-week run of the acclaimed German feature film The Last Laugh at Los Angeles’ Criterion Theater. The Grand Avenue location was one of the city’s first theaters built especially for motion pictures, and just a couple years later in 1927 hosted the west coast premiere of The Jazz Singer with Al Jolson himself in attendance.

Distributor Margaret Winkler married Charles Mintz in late 1923. Her new husband became a business partner and soon Walt interacted more with Mintz than Winkler, a demanding character who favored low budgets and increased output. Anxious to grow his studio, Walt clashed with him from the start.

When Virginia Davis left the series after failed contract negotiations, Dawn O’Day briefly starred in only one film before being succeeded by four-year-old Margie Gay, who appeared in more Alice Comedies than any other actress.

With dark bobbed hair, Gay was poignantly chic for a mid-20s cartoon. She was joined onscreen by her animated co-star Julius, a clever and flexible animated cat who took the dominant role in their adventures. Walt was favoring animation over live-action. Now absent real-world bookends, stories were told entirely in animation with the addition of the live-action girl. Alice herself would play a limited role in plots.

In early 1927, Kansas City animator Isadore “Friz” Freleng was hired, another of Walt’s young staff who’d become a seminal figure in Hollywood animation, in his case at the Warner Bros. animation studio.

Freleng would remember an incident during production of Alice’s Picnic in 1927, which starred Lois Hardwick, the last of the Alice actresses. Friz’s scene— a mother cat washing her kittens—had only a bare description to go by. So he improvised an elaborate series of actions which caught Walt’s attention. He pointed out to the other artists that Friz made one kitten “act like a little kid,” continuing, “That’s what I want to see in the pictures, I want the characters to be somebody. I don’t want them to just be a drawing.”

As historians J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt point out, this was a precocious moment, with great significance in hindsight. As Freleng himself would explain, “The trick in the early days was just to make [the characters] move… But when Walt got into distinguishing one from another by personalities, then it changed the whole thing.”

Walt’s own vision for what he might achieve in animation all but guaranteed the conclusion of the Alice Comedies in 1927. The format had become limiting. Without the requirement of a live-action star, stories and scenarios were limited only by the imagination and the abilities of the artists and technicians. Walt left live-action behind and wouldn’t return to its onscreen use in over a decade.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (in order of appearance):

- Film still from Alice’s Wonderland, c. 1923; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library

- Margie Gay and Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio staff, left to right: Ham Hamilton, Roy Disney, Hugh Harman, Walt Disney, Margie Gay, Rudolph Ising, Ub Iwerks, Walker Harman, c. 1925; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library, © Disney

- Walt Disney, Margie Gay, and Roy Disney pose with camera, c. 1925; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library, © Disney