Walt Disney’s Melody Time celebrates its 70th anniversary this year. Released in May of 1948, it was one of the last of the so-called package features, which took precedent from Fantasia (1940) by combining more than a half dozen short subject cartoons, each musically inclined.

Walt Disney’s Melody Time celebrates its 70th anniversary this year. Released in May of 1948, it was one of the last of the so-called package features, which took precedent from Fantasia (1940) by combining more than a half dozen short subject cartoons, each musically inclined.

It was a tumultuous time in Walt Disney’s life. In the wake of the Second World War and facing grim financial strains, everything seemed tinged with uncertainty. “Those were lost years for us,” as Walt’s brother Roy would later comment.

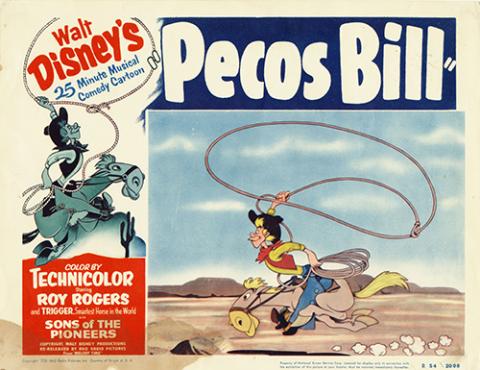

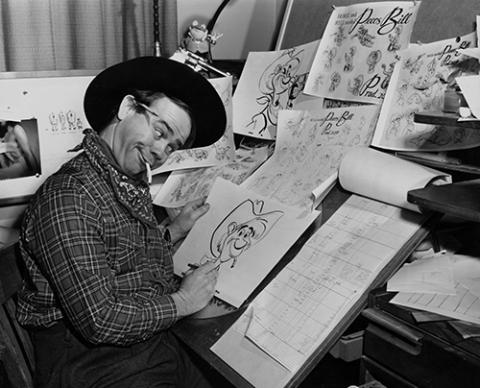

Of the many sequences in Melody Time, a particular stand-out was “Pecos Bill,” a wild, western tale of the mythical folk hero and his female counterpart, Slue Foot Sue. Narrated by popular cowboy star Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers, the animated story was ripe with imagination and broad, expressive comedy. In an unusual pairing, major animation duties on “Pecos Bill” were split between master animators Ward Kimball and Milt Kahl.

In late January of 1947, Walt and his artists convened for an animation review of the work then-in-progress on “Pecos Bill.” These meetings were often referred to as a “sweatbox,” harkening back to the days at the Disney studio on Hyperion Avenue where the confined, stuffy screening rooms combined with the stress of having one’s own work up for critique.

As the animation played for Walt onscreen, Ward, Milt, and the others waited with hushed anticipation. The material was seen only in its pencil-test form; inking, painting, and the backgrounds were still to be completed.

As Ward described it, Walt’s reaction came as quite a surprise to the group. “That’s the greatest inspirational lift I’ve had in six years,” he told the artists.

Ward and the others didn’t know what to say. They must have looked to each other with a mix of confusion and astonishment. As Ward described, there were almost signs of tears in Walt’s eyes. “Thanks, boys for the swell job,” he told them.

The artists weren’t sure what to think as the sweatbox screening ended and they returned to their desks. Why would something as routine as an animation review stir up such emotion in Walt?

Perhaps it was a useful reminder in the midst of hard times, a reminder that the same skill and ability that had existed at the Studios in years past had by no means been lost. Most importantly for Walt, it must have been a small sign of hope for the future.

Time and again, Walt Disney’s tenacity proved the essential ingredient to his success. His unbending commitment carried him through many challenges which likely would have defeated others. Things would always get better, if only one was willing to work for it.

It is affirmation enough to think that within a decade new animated and live-action features would debut, multiple television programs would launch, and Disneyland Park would open.

It was the uplifting power of good drawing and good storytelling that kept him going. Walt believed in his team’s ability to carry him through it, and they believed in him to show them the way.

With sincerest thanks to Ward Kimball’s family for generously providing the material to help elucidate this story.

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.