In the late 1950s, Walt Disney would reflect on much of his life in a series of interviews with journalist, Pete Martin. During one such discussion, Walt remembered a time nearly 20 years before when his animation studio was nearly bursting at the seams with creative and technological innovation. He’d recount a desire he then had to make his pictures more believable and lifelike, “I wanted to get certain effects for a feature. I felt like I had to get a certain feeling of depth and things; I couldn’t just have the flatness. ...And that’s what we now call the multi-plane camera where instead of it being a painting on one plane, we make the painting into several planes and then we can move the camera through the planes and that gives an illusion of depth, you see.” This multiplane camera was unlike anything ever used before at Walt’s studio, and in particular it was a favorite tool on his second feature film, Pinocchio (1940).

The scene opens on a foggy evening. The camera pushes through wisps of mist thick as smoke. A feint light is revealed, hanging over a doorway and dangling sign, “Red Lobster Inn.” In the background lie ships at dock, hulking masses nearly shapeless in the fog. The disquieting camera dolly is broken by a seamless dissolve to inside the building, as Honest John jubilantly sings “An Actor’s Life For Me.” The camera continues to push forward through a veritable maze of architecture, woodwork, and cigar smoke. Finally, the image rests on Honest John, joined by Gideon and the evil Coachman, tucked away in a corner booth of the establishment.

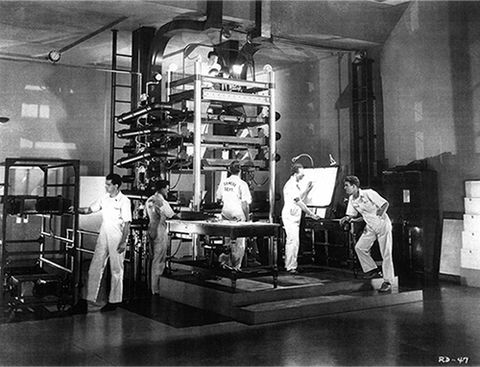

So begins sequence seven of Walt Disney’s epic animated feature, Pinocchio (1940). Directed by artist T. Hee, this opening scene was made possible only by the near magical abilities of one of the Walt Disney Studio’s greatest inventions, the multiplane camera. Designed by Studio master technician, Bill Garity, the multiplane as envisioned by Walt did wonders to add depth, texture, and a new sense of spatiality to animated films. Towering over a dozen feet into the air, the camera system used multiple layers of background, middleground, and foreground, placed at varying heights beneath a camera at the top. The result was a whole new rulebook of cinematographic possibility in Disney films. Pinocchio would see some of the most complex and visually enticing multiplane sequences in history.

The camera dolly towards the Red Lobster Inn and dissolve to the plotting villains inside is literally thick with aesthetic interest. As a period magazine described, “As many as nine celluloid levels were used at one time in shooting the interior of the Inn. The scene, occupying 16-seconds on the screen, is approximately 23-feet in [film] length and took a crew of five men 46 consecutive hours to film it, one crew relieving another.” What this sequence effectively demonstrates is the multiplane’s ability to convey as much texture as it could depth. The multiplane’s possibilities for application were as numbered as the many levels in its structure. This versatility was perfect for a tool envisioned by Walt Disney, who was constantly searching for new and better ways to tell stories.

The foremost and often celebrated use of the multiplane’s wondrous ability came in sequence two of Pinocchio, “Goes to School.” For this momentous camera movement, Walt ensured that every detail was accounted for. Technician Bill Garity designed an expanded version of the original device, this time working on a horizontal plane that stretched across an entire room, yielding a greater freedom of movement. Walt’s team would create a camera motion unlike any other, as the scene begins on a glorious morning, bells ring and doves fly. As if on a dolly track in a live-action film, the camera continues to truck through the village below, turning laterally as school children pour into the streets, and finally coming upon Geppetto’s workshop.

The sequence was, as historian John Canemaker describes, “one of the most renowned and complex shots in Disney’s oeuvre. The time-consuming, painstaking effort expended on this single scene by dozens of personnel… resulted in one of the most expensive single shots in an animated film at the time: $45,000 in those nonunion days [nearly $1.8 million today].” At the time of Pinocchio, Walt was willing if not insistent to ensure the utmost of quality and detail in every element of the film. The richness of a feature film could be as limitless as Walt’s imagination. An unbridled camera could seemingly move gracefully through an idyllic village as characters simultaneously moved throughout the environment. In reality, the environment was five large glass paintings, propped in mechanical frames, lit from all sides, with a camera slowly proceeding through, one frame at a time. The result was pure magic.

In celebration of this epic classic, our newest special exhibition, Wish Upon a Star: The Art of Pinocchio will be on display in the Diane Disney Miller Exhibition Hall through January 9, 2017.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Sources

-Canemaker, John, and Herman Schultheis. The Lost Notebook: Herman Schultheis and the Secrets of Walt Disney's Movie Magic. San Francisco: Walt Disney Family Foundation, 2014. Print.

-Kaufman, J. B. Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic. San Francisco: Walt Disney Family Foundation, 2015. Print.

-Perk, Hans. "In Glorious Multiplane 2." A. Film L.A. N.p., 5 Aug. 2008. Web.