When Walt Disney and his eponymous company entered the new decade of the 1960s, there was no doubt that The Walt Disney Company was on the move.

Just a few short years prior, Walt realized one of his greatest dreams with the opening of Disneyland in July 1955, giving the company newfound financial security and allowing Walt to continue branching out into new forms of entertainment. In the latter half of the 1950s, he continued investing heavily in television—an experiment that began in earnest in 1954 with his Disneyland television show—while producing live-action and nature films. He even opened a recreational center in Colorado. Animation, while not forgotten, was no longer Disney’s lone economic force and Walt began to set his sights on new horizons.

In January of 1959, Disney released Sleeping Beauty, and while the film would become a classic, it did not recoup its cost in its initial theatrical release. By the end of its run, the film only grossed $5.3 million on a $6 million budget—twice as expensive as Walt’s previous animated films Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953), and Lady and the Tramp (1955). While undeniably artistic masterpieces, the lush, detailed, and stylized widescreen backgrounds designed by Disney Legend Eyvind Earle drove up costs. In the aftermath of its release, Walt cut the Studios’ animation staff significantly, and it was three decades before the Company made another fairy tale-inspired film.

As the 1950s drew to a close, while the Company was experiencing more financial success than ever before thanks to Disneyland, feature animation—one of the Company’s signature endeavors—had an uncertain future. As Disney Legend Marc Davis recalled, “The attitude of the business people was, ‘It takes too […] long to do these features, they cost too much, we think you shouldn’t do any more.’”

101 Dalmatians Characters: A Broad Appeal And Unique Style Sets Up The Film For Success

Despite this, Walt continued production on what would be the penultimate animated film released during his lifetime. Based on Dodie Smith’s The Hundred and One Dalmatians, this film had to succeed if feature animation was going to continue. Fortunately, Walt recognized the widespread appeal, particularly from a character standpoint, in Smith’s story. In an interview with Pete Martin of The Saturday Evening Post, Walt explained, “[Sleeping Beauty] was not the kind of picture to have the appeal that [One Hundred and One Dalmatians] had. Because in [One Hundred and One Dalmatians,] I had those cute personalities to hold it, you know, and it had more of a broad appeal. Sleeping Beauty was more of […a] spectacular fantasy.” Walt was right. Released in 1961, Dalmatians was a box office success, grossing $14 million at the box office and proving that Disney feature animation could still be a profitable endeavor.

It has now been more than 60 years since One Hundred and One Dalmatians debuted in January 1961, and while it remains a quintessential Disney animated film, it also marked a drastic departure from the animated features Walt produced during the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. In many ways, it bears little resemblance to anything that came before or after it. Taking on a contemporary story was unique and groundbreaking given the nature of previous Disney films. Disney Legend Andreas Deja notes: “A Disney film set in our time was something brand new. And there’s a realism the contemporary story brings, including a complete lack of magic. Nobody has any special powers. Cruella is just bad.” Further, One Hundred and One Dalmatians brought a new look and feel to Disney animation—one that Walt was not entirely satisfied by—that would alter the look of Disney animated features for decades to come.

The Film’s Unique Animation Style is Stylized and Geometric

During the 1950s, animation had begun to take on a new look that was far more stylized in nature. Groups like UPA started to gain traction with modernist and avant-garde designs and productions. Over time, the realistic and detailed work of the 1940s started to gradually give way to a much more angular, geometric look. While Walt continued to produce classic fairytale films that centered on delicate storybook artistry, other studios were experimenting with this new and stylish design.

It took the artistic talents of Disney Legends Ken Anderson, the production designer on One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and Walt Peregoy, the film’s color stylist, among others, to move the Studios in this direction. Anderson was a tenured company man, starting at Disney in 1934 on Three Orphan Kittens (1935), one of Walt’s Silly Symphony short films. Over time, he proved his versatility, becoming accomplished in animation, scene layout, art direction, character design, and more. By the time he retired in 1978, he had worked on Disney films spanning from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) to Pete’s Dragon (1977)—the latter for which he designed the titular dragon, Elliott—and earned a window along Main Street, U.S.A. in Disneyland. Peregoy, on the other hand, had been in and out of the Disney Studios for some time, beginning as a short-term “traffic boy” at the age of 17 after dropping out of high school. He returned in 1951 as an inbetweener. Disney Legend Eyvind Earle noticed his talents and brought him on as a background painter for Sleeping Beauty, a job that would lead to his role as One Hundred and One Dalmatians’ color stylist.

New Xerox Technology For Hand-Drawn Animation

In May 1958, Ken Peterson, head of the Animation Department, wrote to Walt, “Ken Anderson is making some very interesting experiments on a new style of background and layout handling for this picture. Everyone is very enthusiastic about the possibilities.” These experiments were some of the Studios’ early trials of the Xerox process—a process that began in earnest over a year prior. Disney Legend Ub Iwerks, famous for being the first animator of Mickey Mouse and a notable inventor of camera technologies, filed a series of patents for various methods that would enable xerographic powder to be transferred onto sheets of cellulose acetate—otherwise known as animation cels. To test it out, the Studios utilized it for a few scenes in Sleeping Beauty and the entire animated short Goliath II (1960). One Hundred and One Dalmatians, in part due to the demands of drawing hundreds of Dalmatians and spots, would be the first feature to utilize the method in its entirety.

The Xerox process brought a new aspect to hand-drawn animation. Prior to One Hundred and One Dalmatians, the animators’ drawings had always been transferred to the celluloid sheets by inkers, who would reproduce the lines onto each cel individually. The Xerox process removed the need for this work and transferred the animators’ drawings directly onto the cels. The animators were, unsurprisingly, enthusiastic. For the first time, they would be able to see on-screen the characters and their movements exactly as they drew them. As Disney Legends Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston explained, “There was very little delicacy in the result, and a light line was apt to drop out entirely, but the animator’s drawing was there—strong and irrevocable in the blackest of lines.”

Anderson, speaking for the way many animators at the Studios felt, summarized the difference between the hand-inking process and the Xerox process succinctly in a 1978 interview: “I was very aware from having animated myself that when you had an inker make a tracing of your drawing that it lost some of the life. I found out by experimenting that you can’t even make a tracing over a light board yourself of the same drawing. The tracing looks dead, but the one underneath it somehow or other has the spark of life, because it was conceived because of an idea or an emotion. I always thought that was true when we would run tests in black and white; the animation had more life to it.”

How the Xerox Process Transformed The Background of 101 Dalmatians

Using the Xerox process allowed for the direct transferring of animators’ work, however, Anderson wanted to take it a step further—he wanted the characters and the backgrounds to feel cohesive and unified. To achieve this, Anderson turned to Peregoy who, working closely with layout artist Ernie Nordli, took the background drawings and printed them onto a separate animation cel. These were then laid over the painted background to give it a look similar to that of the characters themselves. Given the reins, Peregoy ran with the film and turned its backgrounds into his own. “From the gal walking down the sidewalk with this dog, the whole thing is the way I saw it,” he recalled decades later in an interview with Julie Svendsen. He explained his method in detail during an interview in 1992:

I painted deliberately with the awareness that it was not necessary to go in and render […] a doorknob, or a piece of glass, or a tree. In One Hundred and One Dalmatians, the background painter did not highly render the background.

Indeed, instead of finely rendering each object in the background, each background was limited to, for the most part, solid matte colors representing each object in the frame. Dark black lines then provided the texture and detail. The result of these efforts is clear on the screen, with the characters seamlessly blending with the world they inhabit in a way previously unseen in Disney animated films. While there was certainly incredible artistry in the backgrounds of feature films like Pinocchio (1940) and Sleeping Beauty (1959), the fact that the characters were hand-inked with delicate lines created a separation from the detailed, multi-dimensional backgrounds that provided the settings for the films. This is not to say that the backgrounds in One Hundred and One Dalmatians lacked depth and dimension in their own right, to the contrary, the backgrounds possessed an incredible amount of texture. For the first time, there was full integration of the characters and the backgrounds, with Anderson even opting to use cel paint for the backgrounds to maintain a consistency of color and look.

What Makes the Artistic Style of 101 Dalmatians Completely Unique

One Hundred and One Dalmatians is unique in this respect. The artistic style of the film would never again be duplicated in its entirety, even as the Xerox process became the standard for decades to follow. For future animated features, the backgrounds drifted back towards the feel of earlier animated films—creating an almost hybrid style that had its own unique presence on the screen. As animation historian Michael Barrier explains, “Anderson received screen credit for art direction on the next Disney animated feature, The Sword in the Stone (1963), but there is no sense, as in Dalmatians, that the boundary between characters and backgrounds has been erased.” Walt Peregoy felt similarly, noting in an interview that “I kept Woolie [Reitherman] at bay on (The) Sword in the Stone,” a film for which Peregoy was also the color stylist, “but his attempt was to gel the Xerox lines against the backgrounds […] there’s no point in that. It’s superficial that the film looks that way.” Whereas in One Hundred and One Dalmatians the black background lines often do not line up with the colors of the objects being portrayed, in The Sword in the Stone the objects are outlined by the black lines perfectly. Peregoy continued, noting that “[The] Aristocats (1970) looks like a classically painted Disney film with Xerox lines on it.’” Of course, Peregoy may have been overly critical of the backgrounds in these subsequent films, but he is not wrong in his identification of their departure from the style laid out in One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

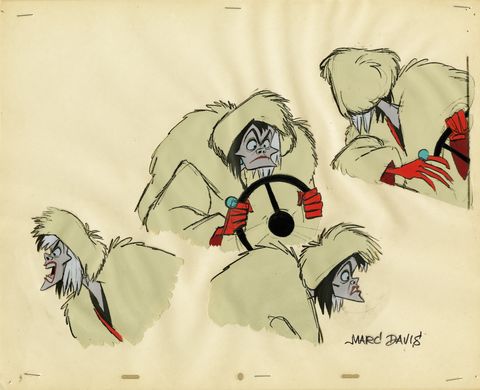

One of The Most Iconic 101 Dalmatians Characters: Cruella De Vil

The backgrounds and Xerox process, while the most groundbreaking aspect of the film, were not its only highlights. For one, the film benefitted from some of the Studios’ finest character animation, particularly with regards to Marc Davis’ work on Cruella De Vil, his final assignment for The Walt Disney Studios, and the conclusion to a storied animation career. In an interview three decades later, Davis remarked that “I think I enjoyed working on Cruella more than any of the others […she] operated without magic, unlike any characters in Sleeping Beauty, Alice [in Wonderland], or Cinderella (1950) […] She’s pure evil, and that’s what makes her interesting […] I did all of Cruella De Vil, every scene of her.” In his work on Cruella, Davis drew inspiration particularly from the commanding and boundless voice of actress and Disney Legend

Betty Lou Gerson. Davis recalled that her vocal performance gave him all he needed to know about Cruella’s presence and personality. “This character was bigger than life, high in energy, and—like a shark—always moving,” he explained. Despite her pencil-thin figure, Gerson’s voice combined with Davis’ animation of her oversized fur coat gave Cruella an undeniable and weighty presence—the makings of a classic Disney villain. Of course, Marc Davis was not alone in providing the film with memorable characters. Other Disney animation greats, including Disney Legends Milt Kahl and Ollie Johnston, worked on the film.

Davis’ iconic Cruella De Vil benefitted from the brilliance of storyman Bill Peet. As part of an effort to reduce film budgets, Walt had been trying to streamline the overall filmmaking process, giving more control to fewer people on films. Disney Legend Woolie Reitherman recalled that “[For One Hundred and One Dalmatians] Walt was trying to simplify the team and the thrust of things. Writer and Disney Legend Bill Peet became the only story man on the script. Before there used to be dozens of them. Bill did a really good job on that picture. Funny man—a very, very talented man.” Indeed, Peet adapted and developed the storyline and dialogue almost single-handedly.

As animation historian John Canemaker notes, “Davis’ animation was supported by Bill Peet’s brilliant adaptation of the story and the storyboards he drew himself without a crew; Cruella’s dialogue, basic look, and staging are all found in Peet’s boards.” Ray Aragon, who worked in the Layout Department during the film’s production, recalled that “Peet’s storyboards were like layouts. I would look at his boards and his boards were alive. Like the characters: The way they move and walk.” In an interview given in 1988, Peet remembered it as his favorite film to work on, despite having worked in some form or another on nearly every Disney animated film from being hired by Walt in 1937 through his departure during production on The Jungle Book (1967).

Walt Disney’s Criticism of 101 Dalmatians

It is no secret that Walt was critical of One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Having spent years trying to perfect animation as an art form, to him the Xerox process seemed to destroy the illusion of life created by finely inked animated characters. Ken Anderson recalled, “I realized that [Walt] didn’t like anything to show lines. In fact, he was trying to eliminate the lines from the very beginning. He didn’t want them to show ever. Didn’t want people to know an animator had drawn them. Snow White would be a girl. The boy would be a boy. They wouldn’t have any lines at all if possible.” Since the Xerox process created dark black lines around the characters, the delineation of the characters lost its subtlety – the lines no longer blended with and became part of the characters they outlined. This can be seen examining the villains of Peter Pan (1953), and One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Whereas Captain Hook is outlined in colors that blend seamlessly into his skin, his clothes, and even his hook, Cruella is outlined in solid black. One could seemingly watch Peter Pan without ever thinking about the lines giving form and shape to characters like Hook, but they are plainly evident throughout One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Walt also was not fond of the background style, and the movement back towards more traditional Disney animation backgrounds was, in part, due to this. For many years after the release of the film, Anderson felt the sting of Walt’s displeasure:

“Anyway, everyone was eventually happy except Walt. Walt hated the way I had done the film. Just hated it […] He took me off direction. ‘Woolie will do all that from now on,’ he grumbled. I was hurt. I stumbled along to other work.”

Of course, Anderson’s work did not end there, and he would continue to be influential in later films. Anderson felt that, eventually, Walt looked past his initial skepticism of the film’s look and warmed to the picture. Recalling their final meeting before Walt’s passing in December of 1966, Anderson recounted that “Years later, Walt left the Studio as a sick man […] I happened to be out on the lot and saw him. He had shrunk. He looked like a little man […] ‘Sure good to see you,’ I said. ‘Sure good to be back, Ken […] It’s wonderful,’ he said. He was looking over the Studio to see what was going on. The way he looked at me, I knew he was forgiving me for making One Hundred and One Dalmatians the way I did. I don’t know how I know it but I knew he was forgiving me.” Walt passed two weeks later.

The Lasting Impact of 101 Dalmatians

60 years after its debut, One Hundred and One Dalmatians remains one of the Studios’ finest achievements. With its contemporary style—characterized by bold colors, angular shapes, and a uniquely modernist flare—it is perhaps the most stylistically unique of all of Walt Disney’s animated films. Departing from the storybook feel of films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty, the film captured a whole new generation of movie-goers with its broad and universal appeal just as the 1960s dawned. Further, its massive success coupled with its relatively low budget made possible by the Xerox process proved the Studios’ Animation Department was still a profitable component of the Company. In the end, while Walt may not have appreciated the film’s aesthetic, he certainly still liked the story and, after all, the story is the most important part. Describing the film to Pete Martin, he noted that “those stories don’t come along very often […]. This one, it was right there.”

– Parker Amoroso, blog contributor

Image sources (in order of appearance):

-

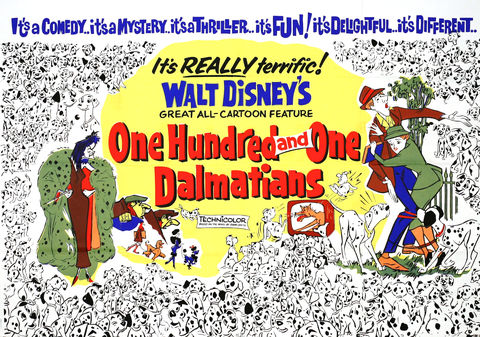

Half sheet movie poster, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Ron and Diane Miller; © Disney

-

Photograph; Walt Disney reviews Sleeping Beauty backgrounds by Eyvind Earle, c. 1950; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, Gift of Ron and Diane Miller, © Disney

-

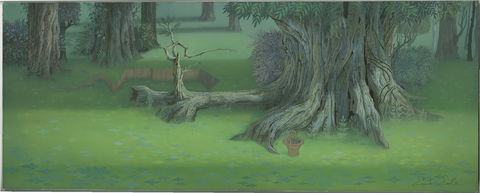

Earle, Eyvind; Background painting, Sleeping Beauty (1959); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, © Disney

-

Background painting, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

-

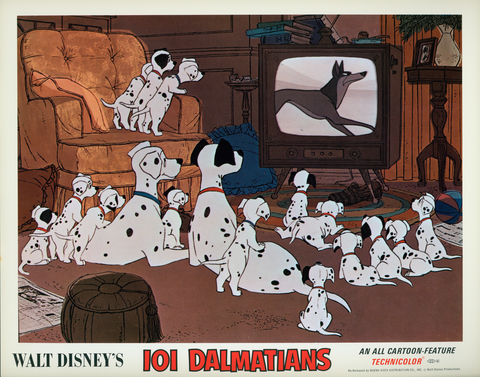

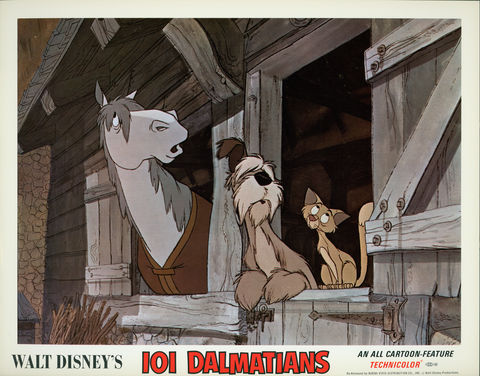

Lobby card, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Dean Barickman; © Disney

-

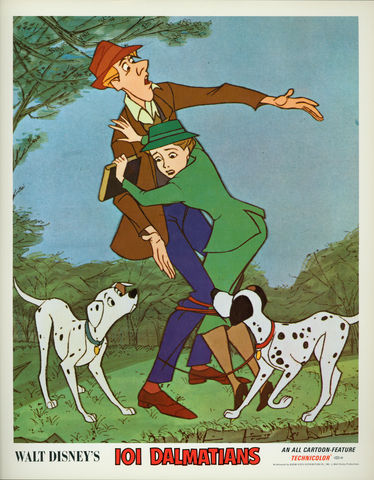

Lobby card, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Dean Barickman; © Disney

-

Davis, Marc; Visual development for One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

-

Cel, Captain Hook from Peter Pan (1953); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Walter E.D. Miller; © Disney

-

Lobby card, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift of Dean Barickman; © Disney

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.