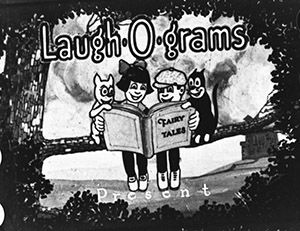

While Walt was working at the Kansas City Film Ad Company (highlighted in Gallery 1B), he taught himself the art of celluloid animation and borrowed a camera from work to begin making experimental films of his own. With the experience he gained from this, he contacted some of the artists he worked with at Kansas City Film Ad to join him on a new venture. In this new venture, they would create a series of short fairy tale cartoons updated with Jazz Age gags for prominent Kansas City theater owner Frank Newman to play before films in his theaters. The film series would be called Newman Laugh-O-grams, and Walt’s new company would take its name from it: Laugh-O-gram Films.

Laugh-O-gram’s first—and only—big contract came from a group called the Pictorial Clubs who offered $11,000 for a series of 6 shorts, with an upfront payment of $100. Unfortunately, following the completion of production on these shorts, Pictorial Clubs went bankrupt, having only paid Walt the initial $100. Walt tried several projects to save his company, including a film on dental hygiene for Dr. Thomas B. McCrum (Tommy Tucker’s Tooth) and an inventive film with a live-action girl in a cartoon world (Alice’s Wonderland), but neither were able to keep Laugh-o-grams from having to declare bankruptcy. This was Walt’s first poor experience with an outside distributor for his films, and encouraged him to take a more discerning look at future contracts.

Undeterred and in partnership with Roy, Walt decided to start over in Hollywood in 1923 with a new independent animation studio, the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio. With his Wonderland film in hand, Walt contacted one of the biggest cartoon distributors of the day, Margaret Winkler of Winkler Pictures, about the potential of his new studio. Margaret Winkler was receptive to the Alice reel and agreed to move forward with a series, provided that Walt could retain young Virginia Davis as Alice. This proved to be little more than a mere roadblock for Walt as, in true salesman form, he penned a three-page letter to Virginia Davis’ mother successfully persuading her to move the family out West to pursue Virginia’s movie career. Successfully selling the Alice Comedies to Winkler and Hollywood to the Davis family emboldened Walt with the confidence that if he truly believed in a product or idea, he could sell it to anyone.

Around the time Walt and Roy married Lillian and Edna, Margaret Winkler also married a man named Charles Mintz who became the new head of Winkler Pictures. This marked a shift in Walt’s working relationship with his first consistent distributor. Mintz was insatiable and readily disappointed in Walt’s studio output, claiming in a letter to Walt that had he sent any other distributor in the world his first seven Alice films, they would have disposed of them “bodily” and conducted no further business with him (October 6th, 1925)—once even going so far as to call a particular Alice Comedy “just another picture” with “nothing in it whatever that is outstanding” (February 13th, 1926). In an ironic twist, such scathing criticism of Walt’s work on the Alice Comedies was printed and delivered on Winkler Pictures letterhead which prominently featured the Alice Comedies logo and its principal animated character, Julius the Cat.

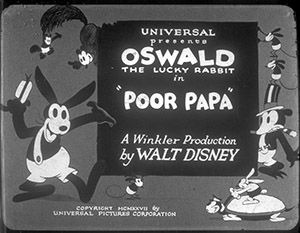

This working atmosphere persisted even as Walt’s staff transitioned to their first fully-animated project in 1927, which would be distributed by Universal via Winkler Pictures. Similar to Winkler’s insistence that Virginia Davis play Alice, Mintz required that the character be a rabbit named Oswald, and thus, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was born. Universal’s involvement meant that Walt’s films were shown in larger and more prestigious theaters, but also came with the caveat that Walt’s work had more critical eyes on it from the distribution side. With the knowledge that he was relying on the money and reach of these outside distributors, Walt understood that he had to be flexible with the feedback he received from these powerful interests in order to secure their continued support.

In an uncharacteristically lengthy discourse with Mintz in April 1927, Walt gave his appreciation that Universal offered a number of revisions on the first-produced Oswald picture Poor Papa (1927), but broke each criticism down point-by-point as to why his staff made the decisions they did and how he felt they could improve, concluding: “I always welcome criticism because I realize that we, being so close to our work, may fail to get the correct general ideas. […] I really am glad that Universal […] has taken the interest shown. It makes all the boys and myself feel that hard work, effort resulting in good pictures is going to be rewarded with good distribution, backed by a live sales organization that knows what they want” (April 21st, 1927). Despite his accommodating and self-effacing tone, Walt’s impassioned defense of his studio’s “good pictures” conveys how much he believed in his product and his reluctance to overhaul what may not need fixing.

Oswald was a hit with audiences and critics alike and benefited from the exposure of Universal’s distribution range. As the Oswald contract with Winkler Pictures wound down, Walt saw the increasing costs of making the Oswalds and felt secure in asking Mintz for a modest raise on behalf of himself and his staff. To Walt’s surprise, Mintz not only rejected his request for a raise, but instead demanded that he take a pay cut or else lose his staff—many of whom had arranged back-room deals with Mintz to continue making the Oswald pictures if Walt did not agree to his terms. Oswald was Universal’s property, which gave Mintz the ultimate leverage, and there was nothing Walt could do to save Oswald without working underneath someone else. While this rude awakening did lead to the creation of Mickey Mouse—a much more successful cartoon star than Oswald ever was—it also taught Walt a hard and valuable lesson about owning the characters he created.

Plane Crazy, the first Mickey short produced, played in front of a test audience and did not attract the attention of new distributors. A common refrain heard by Walt was that nothing about this new mouse character stood out against other cartoon characters of the day. The advent of the talking picture ushered in by The Jazz Singer (1927) prompted Walt to consider a new frontier for his cartoons to explore: synchronized sound. Walt’s limited budget to approach the sound process led him to the office of Pat Powers, one of the founders of Universal Pictures. Powers had his own sound recording business that he operated at a fraction of the cost of the industry heavyweights such as RCA (Walt remarked, “All around we will get a far better deal from POWERS than we will get from any of the others . . . . and his recording is equally as good if not better than the others”—Letter to Roy and Ubbe, September 1928). He agreed to distribute Walt’s cartoons through his label, Celebrity Pictures—an offshoot of Columbia Pictures—and let him use his Cinephone recording process.

While Walt inferred that Powers was more interested in promoting his sound technology than advancing the cartoon medium, Walt did not know that Powers’ Cinephone technology was actually a cloned version of the already-established Phonofilm sound-on-film system pioneered by Lee de Forest, the “Father of Radio.” In an unsuccessful bid to take over de Forest’s Phonofilm Company, Powers had hired away technician Bill Garity to develop a near-identical sound system, to be labelled “Cinephone,” for his own company to license out. This validates Roy’s later assertion that Powers was “… a crook! A definite crook!” Garity would eventually come over to The Walt Disney Studios where he would develop Disney’s Academy Award®-winning multiplane camera and Fantasound sound system.

Out of his overwhelming desire for sound equipment, Walt did not thoroughly read his contract with Powers, which he would later come to regret. The contract allowed Powers to advance Walt money on each film against the film’s expected profits, but without a receipt showing just how much each Mickey cartoon was earning. Upon Roy’s revelation that they were likely being swindled, they hired Gunther Lessing as company attorney and began satisfying all remaining legal requirements still owed to Powers while they looked for a more mutually beneficial distributor relationship. Much more serious in temperament than the boss, Walt famously joked to visitors that Lessing was “The only Mister we have at the Studio.”

In response to this, Powers hired away Ub Iwerks—one of the only artists to stay loyal to Disney while nearly the rest of the staff was being poached by Mintz in the year prior—to form his own independent animation studio. Carl Stalling, the Studios’ composer, left around this time too, joining Iwerks’ studio for a while but eventually leaving for Warner Bros. where he would gain legendary status arranging and composing music at a breakneck pace, averaging a complete score every week, for their “Looney Tunes” and “Merry Melodies” series until his retirement 22 years later. These were devastating losses to Walt, reaffirming to him that reliance on outside businesses to perform important functions in the filmmaking process, particularly those run by big New York or Hollywood film executives, resulted in an uncomfortable amount of leverage switching hands.

Following Walt’s defection from Powers, Columbia expressed interested in continuing their partnership with Disney even without Powers as a middleman, so from 1930-1932 Columbia agreed to directly distribute Walt’s new inventive Silly Symphony short cartoon series, as well as continue the ultra-successful Mickey Mouse series.

A falling out with Columbia led Walt to pursue a distribution contract with United Artists from 1932-1937. United Artists was founded by upper-echelon filmmakers D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks as a way for artists to collectively support their own endeavors as opposed to depending on the financial backing—and ultimately, final say over the finished product—of the powerful commercial studios. It was during Walt’s time with UA in which he released two of the most consequential animated short films ever made by The Walt Disney Studios: Flowers and Trees (1932) and Three Little Pigs (1933). Flowers and Trees is significant for being the first cartoon to utilize Technicolor’s new vibrant three-strip color process (for which Walt bargained for a 3-year window of exclusivity). Three Little Pigs is significant for its progression in personality and character animation and spawning an anthem of the Great Depression in “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” Both films netted Walt Academy Awards in the Cartoon classification of the Short Subject category, a category inspired by the strides Walt and his Studios were making in transforming animation into an art form.

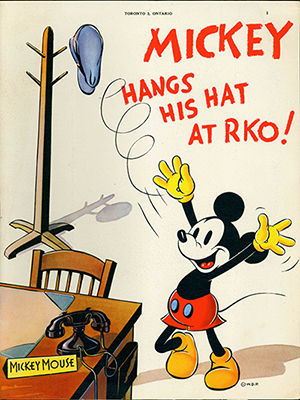

Walt’s reluctance to sign over the television rights to his cartoons to United Artists, when the new television medium had not yet proven its staying power, led him to secure a contract with RKO Radio Pictures, who would distribute the final Silly Symphonies, including 1937’s The Old Mill—which introduced the world to Disney’s multiplane camera—and the last Mickey Mouse shorts (in their original run). RKO famously took the plunge on distributing Walt’s feature pictures starting with “Walt’s Folly,” Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), as well as a selection of shorts made at-cost for the U.S. WWII effort on the home-front. RKO distributed Walt’s most ambitious animated features in what would later be defined by many as the Golden Age of animation. While placing the full faith and credit of RKO behind such ambitious technical marvels as Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), and Bambi (1942), Walt would run into the problem of an anxious distributor’s overriding veto once more.

Near the end of the 1940s, Walt was disheartened at the reluctance of RKO to distribute his new project, Seal Island (1948), the pilot film in his new True-Life Adventures nature documentary series. Following a string of successful features—perhaps most notably Cinderella (1950), Treasure Island (1950), and Peter Pan (1953)—Walt felt he was finally in a financial position to team up with Roy in creating their own distribution company. Walt was understandably frustrated that even with his established track record, RKO was still willing to flex their ultimate veto power over his product reaching the public. To convince RKO that audiences would be interested in his nature documentaries, Walt arranged with a Los Angeles County theater to show his Seal Island film for one week, the minimum amount of time required to qualify for an Academy Award. To RKO’s surprise, Seal Island would subsequently win the Academy Award® for Best Short Subject, Two-Reel in 1949. Disney’s new distribution arm, Buena Vista Film Distribution Company, was incorporated in 1953. Walt’s True-Life Adventures would win a total of eight Academy Awards during its run.

From 1953 on, starting with the documentary The Living Desert (1953), live-action feature 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), and animated feature Lady and the Tramp (1955) and continuing through Buena Vista Pictures Distribution’s rebranding as Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures in 2007, The Walt Disney Company would self-distribute its films, putting no middlemen in between. For television distribution, Walt famously stipulated that any company to get the rights to show Disney programming would have to invest in his Disneyland project—the deal-breaker that gave ABC the upper hand over NBC (until NBC could provide a color format unmatched by ABC in 1961). Disneyland would then open a new avenue to approaching corporate sponsorships, culminating in the acquisition of approximately $50 million dollars of attraction technology development for Walt’s projects at the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair. Through Walt’s varied experience with outside companies, he would take to heart owning his own characters, stories, and means of production; a lesson The Walt Disney Company embodies to this day.

Chris Mullen

Guest Experience Associate at The Walt Disney Family Museum