In the latest issue of The Walt Disney Family Museum’s member magazine, filmmaker and former Disney voice artist Bruce Reitherman shared memories and insights about working on Walt Disney’s The Jungle Book (1967). Bruce was not only the voice of the lead character Mowgli, but also the son of the film’s director, Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman. The conversation between the younger Reitherman and historian Lucas O. Seastrom covered everything from the making of The Jungle Book to Wolfgang Reitherman’s relationship with Walt Disney to Bruce’s own career as a nature documentarian. Due to length, these excerpts from the conversation were not included in the article published in the member magazine.

Bruce Reitherman: Despite the fact that The Jungle Book is about Mowgli, you could make the case that there were a million kids out there who could have performed the voice. All that was needed from me acting-wise was authenticity. The other voice actors were critical in making the film come alive, along with—of course—the incredible story work and animation.

Lucas O. Seastrom: What sort of interactions do you recall having with the other voice talents?

BR: I remember one time being with Phil Harris and Sebastian Cabot, and they had great repartee and energy. We would’ve been in the recording studio where they had these risers where musicians could be positioned. There was a piano in the corner that was always there. There’d be scripts lying around and the day’s work would be discussed and laid out. The other voice talents were so vivid in their personalities. Me listening to them just talking about what they were going to do felt like a captivating performance to me.

Their voices were unique and contrasted with each other, but they shared this warmth underneath. Interestingly, Baloo and Bagheera each loved Mowgli in ways they had a hard time expressing. They were utterly different characters who didn’t really like each other at first—sort of an “Odd Couple”—but they both wanted Mowgli to have a good life, even if each of them had a different idea about what that might entail (at least as they all began their adventure together). It’s a testament to the casting of the movie because it’s grounded in the nature of these actors’ voices. They had such a dynamic but sympathetic energy between them—friction mixed with affection.

LS: That seems to be very much in line with what the creative team at the studio had found success at: developing strong characters and personalities. They were making the source material their own.

BR: There’s a frequently told anecdote about Walt Disney holding a story meeting and asking if anyone had read Rudyard Kipling’s book. The artists sheepishly said “No,” and Walt’s response was, “Good, don’t read it.” Walt hadn’t been happy with the initial attempts to follow the Kipling story closely, and he wanted to go in a different direction.

LS: The studio had done many book adaptations before to varying degrees of loyalty to the original text. Mary Poppins (1964), [The] Sword in the Stone (1963), and Winnie the Pooh [and the Honey Tree] (1966) were all recent examples.

BR: The Jungle Book wasn’t a thing unto itself. It was a movie made in a specific time. That context is important. Mary Poppins had been made a few years earlier, and that film is similar to The Jungle Book in a particular way. Both films are collections of oddball events that on their own are entertaining but don’t necessarily have relevance to the central story itself. In Poppins, you have chimney sweeps on the roof and drawing chalk art on the sidewalk, a tenderhearted old woman selling birdseed on the steps of St. Paul’s… and then a laughing uncle who floats to the ceiling. Those things have little to do with the plot of the story—which is more about the family than the nanny—but it was all so entertaining! These films were both moving away from plot, and focusing on personality, entertainment, and variety. There was this delightfully unexpected quality. Who would’ve thought that you could go from one of these ideas to another if all you knew was that this was a story about a family and their nanny in Edwardian London?

This all precedes The Jungle Book, and I think it shares some DNA. Think of the musical choices, for example. What is going on with Louis Prima, launching into song with a Dixieland jazz band in an Indian temple in the middle of the jungle? What a kooky idea, but in reality, it was perfect. It’s such an interesting choice. Later, you have these four guys who look like The Beatles. You have “Trust in Me,” which is this strange ballad—I mean Kaa the snake is singing a funny song about how he is about to eat poor Mowgli! It always interested me to think about these two films. Disney was searching for something new. Over the years, Walt Disney’s films were alike in some ways, but they were also very different from one another. He was always changing things, exploring new ideas, and taking risks.

I don’t mean to suggest that these story elements are random. In fact, it is because the story doesn’t necessarily demand that the next sequence present an orangutan leading a jazz band that such a choice was genius. There’s this mix between story driven by plot and story experienced as entertainment full of surprises. And you have to admit that it works—on every level.

LS: It’s not that The Jungle Book is episodic in an arbitrary way. It’s partly a road movie with this sense of direction involving a boy trying to return home, but what is home? Well, home is this kind of journey through himself. Road movies are all about stopping along the way and then something happens. There’s a buddy-picture element as well.

BR: Absolutely. There’s this combination of a buddy movie and a road movie where you never quite know what’s around the corner. That’s what makes it delightful. Yeah, at its core, it’s a story about Mowgli’s journey to grow up… to become a man. But it’s all the other bits that make this movie so memorable, so beloved by so many people.

LS: You make a great point that these films weren’t made in a vacuum, and that they exist within the context of each other. Mary Poppins was a kind of apotheosis for Walt, and perhaps you see him flexing his muscles a little more coming out of that experience by deciding to more-or-less scrap Kipling and do his own thing. The bigger theme of risk-taking is there too because at the same time he was at the [1964/65] New York World’s Fair with Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln and “it’s a small world”, and he was preparing EPCOT. He was getting into his riskiest ventures, and he’d taken a lot in the past already!

BR: My dad admired Walt because he would commit himself to make his dreams real, like with Disneyland—a kind of amusement park that hadn’t existed heretofore. He wanted to make a place that wasn’t Coney Island, but somewhere that families could go that had an atmosphere that was almost a narrative—one that was entertaining and wholesome. Even though my dad wasn’t really part of the Disneyland design, as were some of the other Disney greats, I think Woolie admired that Walt was always on a quest to pursue the burning concept in his mind. Walt wanted to be America’s entertainer. Nostalgia was part of it, and through a modern lens today, it might sometimes feel sentimental or romanticized, but in those days, it was simply an homage to the time of Walt’s youth. It wasn’t this ancient thing. It was immediate and sincere, authentic to his own experience. If you’re not doing something that’s really true to yourself, people will see it as phony.

LS: There’s a story that circulates that close to the time of Walt Disney’s passing, he called your father over to the hospital, and they had some kind of discussion about the future of animation at the studio. Some have claimed that Walt sort of handed your father the keys to the unit and entrusted him to carry it forward. What is your understanding about this occurrence?

BR: My understanding is no better than anyone else’s. It’s all a guess, because I wasn’t there, and if anyone else was, they have never described the meeting. So I can’t presume exactly what happened. My mother intimated that dad had gone over to the hospital before Walt passed, but it’s a fuzzy memory for me, and there was no mention of what was discussed. If the meeting ever happened, I think my father would have felt willing, almost reluctantly, to be entrusted with the responsibility to keep animation moving forward at the Studios. But even if Walt had told Woolie that in so many words, what would Woolie have done with that? Get it engraved on a plaque for his desk? Even when Walt was part of the animation process, there were no magic keys or magic wand. The only way to really accomplish what, at times, must have seemed almost impossible was to get down and do the work as a team. Dad understood that making great entertainment in the Disney mode—literally making dreams come true—was just really hard work as a team. So, it will be harder now without Walt… much harder… and I will do my best to lead, but we can do this, so let’s all of us get to it, together.

LS: And it required a massive team effort to accomplish that.

BR: Many of the people still working in animation at the time of Walt’s passing had been in the trenches together for decades, and they’d done seminal, groundbreaking work together. Dad was a brother in arms with them. No one was ever going to fill Walt’s shoes. The animators had to figure out a way to move forward without Walt’s living presence. On a production like The Jungle Book and the following features Woolie directed, he would involve the supervising animators in conversations that involved the whole film, not just the scenes they were specifically working on. They came together as parts of a bigger whole, along with story guys, songwriters, and others—always had, even when Walt was a towering part of the mix. Woolie had been directing for quite a while already—shorts, animation sequences, and then [The] Sword in the Stone, [Winnie the Pooh and the] Honey Tree, so it’s likely that Walt had already made it clear who he thought should lead animation once Walt was gone.

LS: When thinking about Walt Disney, a key word is sincerity. One gets the impression that your father had a matter-of-fact admiration for Walt. They wore their hearts on their sleeves in that way. Years later, your father described completing The Jungle Book in the context of Walt’s recent passing as “survival.” You speak to that need of keeping it alive picture-to-picture, almost like in the earliest years back when they were making Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs [1937] or Pinocchio [1940].

BR: We all have different relationships with our relatives, but it’s kind of a strange and happy thing to grow up in a place where you personally admire your father so much. He was a wonderful husband and father, very creative, and risked his life in World War II. Keeping Disney animation alive was not just about preserving a legacy, it was about moving the [art] form forward… and keeping a lot of people working on the payroll! Animation in those days was expensive, especially compared to some financially successful films of the period, and each animated feature had to generate box office that justified making the next one. Woolie took that challenge very seriously. He understood that keeping to budget and generating films audiences would pay to see was critical to keeping Disney animation afloat.

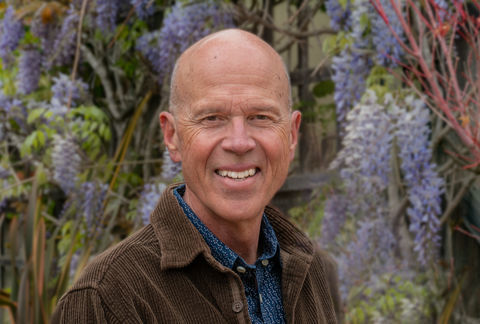

LS: In a way, your own experiences at Disney were the commencement of a larger journey as you became a filmmaker yourself. Could you discuss your introduction to documentary filmmaking and how your interests in nature coincided with that?

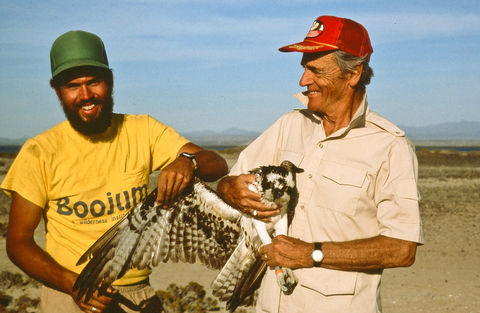

BR: As a young man, I spent lots of time outdoors, leading trips on whitewater rivers in North and Central America, and I had a research program on a small island in Baja California studying birds of prey called ospreys. They catch fish in these lagoons where whales travel to breed in winter. I thought I might go into wildlife biology, but I didn’t think I'd have the patience to finish a PhD or anything that academic. During that period of time, my mom and dad would come down to see me in Mexico, and I was beginning to play around with cameras. Dad encouraged me to take still photographs and write.

LS: And that led into motion pictures?

BR: Natural history films were a big deal by this point in the early 1980s. Remember Jacques Cousteau? And the early BBC films with Richard Attenborough? They were elegantly made with great music and minimal, precise narration. I managed to get a job with a camera because I’d worked previously as a guide in Alaska, and I helped produce a successful television film. From there, I spent the next 25 years working on six continents doing lots of freelance work, as well as eventually producing, shooting, and writing television specials of my own.

I tried to make nature documentaries that didn't feel like lessons. I hoped to capture a sense of what I felt when I was there. Sometimes that means you employ a bit of cinema magic. It’s kind of like animation in the sense that you’re manipulating elements to create an impression of reality… and in the sense that you have to be patient and persistent—you have to love the work, but even more important, you have to care about what an audience will feel when they see the product of all your many hours of effort.

LS: It’s kind of a full circle in the development of your craft.

BR: It can be impossible to get the proper coverage of animals in action, because they’re not actors willing to “go back to one” and hit their marks over and over! In order to create that impression of realism, you need to join pieces together. That goes back to being a kid tagging along with my dad and watching the long evolution of an animated film. So many parts come together in a cinematic language constructed like words in a sentence. I learned that any documentary cameraperson should have a good knack for gathering a variety of shots with the editing process in mind. One little close-up of an animal can make all the difference and give you a chance to make a scene work… to tell a story that feels like life. Hmmm… maybe I did learn a thing or two from working with my father on a movie like The Jungle Book!

LS: It’s heartening to know that the experiences you had as a child at the Disney Studios helped influence your own work in the arts and sciences. And considering your involvement in The Jungle Book, it’s fitting that your journey happened to lead you outside, albeit with a camera.

BR: I suppose that’s right. I went looking for my own version of the “Bare Necessities,” and I guess I'm lucky I got handed a camera instead of a pawpaw!

LS: Thank you very much for sharing these memories and insights, Bruce.

To sign up to read the member-exclusive interview, please click here.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

- Bruce and Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman in Baja California; © Bruce Reitherman

-

© Bruce Reitherman

-

Bruce Reitherman shooting film in Baja California; © Bruce Reitherman

-

Bruce Reitherman shooting film of a Komodo dragon in Indonesia; © Bruce Reitherman