“Ray Bradbury and my father, Walt Disney, had a very special friendship—one of mutual admiration that began, of all places, in Bullocks Wilshire.”

—Diane Disney Miller

In March 2005, Ray Bradbury gave a talk at the Performing Arts Center in Duarte, east of Pasadena. After his talk, I went up and handed him my copy of The Martian Chronicles to sign. I told him I had co-written a biography of Walt Disney with NBA executive Pat Williams, who had interviewed Ray for the book.

“Oh, yes!” Ray said. “Your friend sent me a copy. Would you like to hear how I met Walt Disney?”

I knew the story—it was in the book—but what a treat to hear it from Ray himself!

“It was 1964,” Ray said. “I was Christmas shopping and I saw a man coming toward me, loaded with Christmas presents. I said, ‘That’s Walt Disney!’ I rushed up to him and said, ‘Mr. Disney?’ He said, ‘Yes?’ I said, ‘I’m Ray Bradbury, and I love your movies.’ He said, ‘Ray Bradbury! I know your books.’ I said, ‘Thank God!’ And he said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Because I’d like to take you to lunch sometime.’ And Walt said, ‘Tomorrow?’ Isn’t that beautiful? Not, ‘Next month.’ Or, ‘Someday.’ Tomorrow. Walt was spontaneous. The next day, I met him at his office and we had lunch—soup and sandwiches on an old card table. I told him how much I loved Disneyland, and he was thrilled to hear it.”

And that was the story as he told it to me.

I later discovered that there was much more to the story of that day—and the story of the friendship of Walt Disney and Ray Bradbury. Walt passed away just two years after that first meeting, but they were such kindred souls that they packed a lifetime of friendship into those two years.

In his books Yestermorrow (1991) and Bradbury Speaks (2005), Ray talked about their meeting in Walt’s office. Ray arrived at noon, and Walt’s secretary warned that her boss had a busy schedule. “One hour. You’ll need to leave promptly at one.” Then she showed him into Walt’s office.

Walt and Ray greeted each other warmly. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Walt said, “Nothing has to die.”

Ray soon learned that Walt was referring to the 1964/65 New York World’s Fair, more than a hundred forty pavilions representing eighty nations—and it would all be torn down by the end of 1965. Walt thought it was a senseless waste—and Ray agreed.

Then, eyes sparkling, Walt told Ray his grand idea of a kind of World’s Fair he planned to build in Florida. It would grow and change with the times, but it would never die.

Ray thought it was one of the best ideas he’d ever heard—the kind of idea Ray called a “Schweitzer’s centrifuge.” Albert Schweitzer once said, “Do something wonderful; people may imitate it.” A Schweitzer’s centrifuge, Ray said, is a place where you can figuratively “spin” people (such as a theme park or a world’s fair) and inspire them, ignite their curiosity, stuff their heads with ideas, and send them whirling out into the world to build brand-new dreams.

Disneyland, Ray said, was a wonderful Schweitzer’s centrifuge. He was glad Walt was planning a bigger one in Florida. Ray’s centrifuge metaphor pleased Walt very much.

Ray told Walt about his first trip to Disneyland. Actor Charles Laughton—Captain Bligh in the 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty—took Ray to the Park and guided him around. Their first stop: Jungle Cruise. Laughton reprised his role as Bligh, shouting orders to the other passengers, leaning out to catch a face-full of Schweitzer Falls, and laughing giddily at the skipper’s jokes. Later, Ray and Charlie soared over London aboard Peter Pan’s Flight, launched to the moon from Tomorrowland, and much more. Walt loved hearing Ray tell about their adventures in his Park.

Walt and Ray traded childhood memories of candy stores and horse-drawn milk wagons and silent movies—then Ray checked the time. One o’clock! He jumped to his feet and shook Walt’s hand.

“Wait!” Walt said, “I have something to show you.”

Walt escorted Ray past his glaring secretary and out of the building. He led Ray to the workshop of his Imagineers. There, Walt showed Ray a reanimated Abraham Lincoln and some partially constructed buccaneers for Pirates of the Caribbean. Then he took Ray for a ride on a PeopleMover prototype.

They returned to Walt’s office at three. The secretary frowned and pointed to her watch. Ray gestured to Walt and said, “He did it!”

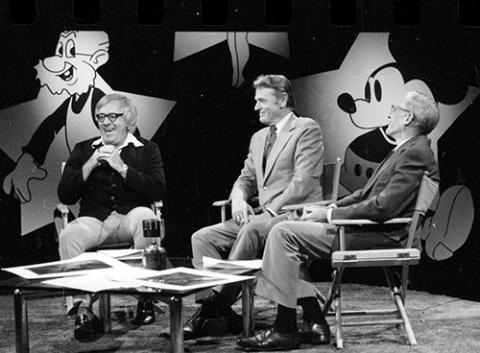

That was the first of Ray’s many visits to The Walt Disney Studios. In later months, Walt introduced him to the writers, artists, and Imagineers who helped him weave movie and theme park magic. During those visits, Ray contributed ideas and insights to various Disney projects.

Ray had recently founded a group called PRIME: Promote Rapid Transit, Improve Metropolitan Environment, for reducing traffic congestion in Los Angeles. Ray recalled:

I watched the blueprinting and laying of the foundations for the Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion, meanwhile planning and replanning cities and malls in my head. One lunchtime I said that Los Angeles needed a really good creative mayor like Walt. His swift response:

“Why should I be mayor, when I’m already king?”

Over one lunch in 1965, Walt told Ray he was going to overhaul Tomorrowland.

“Walt,” Ray said excitedly, “why don’t you hire me to help you with ideas to rebuild Tomorrowland?”

“It’s no use,” Walt said. “You’re a genius and I’m a genius. After two weeks, we’d kill each other.”

Bradbury later reflected, “That was the nicest turndown I’ve ever received.”

Over another lunch in early 1966, Walt said, “Ray, you’ve done so much for us. What can we do for you?”

Without thinking, Ray blurted, “Open the vaults.”

Walt picked up the phone, dialed, and said to someone at the other end, “I’m sending Ray Bradbury over. Let him have anything he wants.” Ray could hardly believe his ears.

He hurried to the Animation Building’s “Morgue,” remembering all the Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoons he had watched in darkened theaters since he was eight years old. He had seen Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs eight times during its first two weeks of release (he paid twice—the other six times were sneak-ins). And Walt had magically given him access to the place where all these beautiful dreams were catalogued and stored.

Moments later, the head of the Morgue led him into the great temple of Disney history—and for a moment, Ray forgot to breathe. There were cels, sketches, and watercolors from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Sleeping Beauty, Alice in Wonderland, Bambi, Fantasia, and countless animated shorts.

Ray pulled out his selections and stacked them on a table, then asked the archivist to place the stack on his outstretched arms. When Ray left with Walt’s gift, he felt he was fleeing an art heist.

In the months that followed, Ray had a few more lunches with Walt. Then one day, someone told him Walt was ill. Ray felt an ominous, wintry chill in those words.

On Thursday, December 15, 1966, Ray was getting ready to meet with film critic Richard Schickel, who was writing Walt’s biography. Ray had the TV on when an announcer broke in with the news: Walt Disney had passed away.

For Ray, it was like a death in the family.

Minutes later, Schickel phoned. “Ray, did you hear the news?”

“I heard. This is a terrible, terrible day. I’m devastated.”

“Would you like to reschedule?”

“Oh no, it’s all the more reason to get together. I want to talk about him.”

On Saturday, December 17, the day Walt was interred at Forest Lawn, Ray took his four daughters to Disneyland. He had promised them this outing weeks earlier. When Ray and the girls returned that night, his wife Marguerite told him that CBS Radio had called, wanting an on-air interview. “I told them you were at Disneyland,” she said.

With tears in his eyes, Ray said he could imagine no finer epitaph than that.

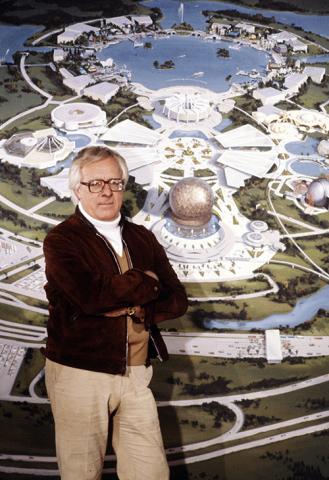

After Walt’s death, Ray Bradbury continued his association with The Walt Disney Company. He contributed visionary ideas and a narration script for the iconic Spaceship Earth attraction at Walt Disney World in Florida.

He also took on the role of defender of Walt’s legacy. Whenever New York intellectuals wrote dismissively about Disneyland or Walt’s movies, Ray would slay the dragons of artistic snobbery with a few strokes of his pen.

Ray spoke of only one unhappy experience at Disney. He wrote the script for Disney’s 1983 screen adaptation of his novel Something Wicked This Way Comes. The director quietly handed Ray’s script to another writer for radical alterations. The first Ray knew that his script had been mutilated was when he saw the completed film. The preview audience hated the film, and Ray was heartbroken.

A few days after the disastrous preview, Walt Disney Studios head Ron Miller invited Ray to his office for a talk. Ray told Miller that the film could still be saved. “Rebuild the sets,” he said, “and rehire the actors.”

Miller agreed with Ray, and The Walt Disney Studios spent $5 million and three weeks re-shooting the film — this time with Ray’s involvement. Ron Miller showed Ray the same commitment to excellence that Walt would have shown. Ray later recalled that Something Wicked was released “to mostly good-to-fine reviews.” It was “not a great film, no, but a decently nice one.”

During a 1985 visit to France, Ray became intrigued with the work of nineteenth century architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Returning home, Ray visited Disneyland. As he approached the drawbridge of Sleeping Beauty Castle, he looked up — and stopped in his tracks. For a long time, he stared at an ornate spire to the right of the tallest tower.

That night, Ray phoned Imagineer John Hench and said, “I just noticed something about Sleeping Beauty Castle. There’s a Viollet-le-Duc spire there that I last saw on top of Notre Dame Cathedral and the Palais de Justice in Paris. How long has that been there?”

“Thirty years.”

“Who put it there?”

“Walt did.”

“Why?”

“Because he loved it.”

“Ah!” Ray said. “That’s why I love Walt Disney. It cost a hundred thousand dollars to build a spire he didn’t need.” And that, Ray concluded, is the secret of Walt Disney—doing things you don’t need, and doing them well. Then you realize you needed them all along.

In the late 1980s, as Disney was preparing to build a new theme park outside of Paris, Ray hung out at Walt Disney Imagineering in Glendale, talking to the Imagineers who had known Walt, such as John DeCuir, Sr. and Harper Goff, plus many post-Walt-era Imagineers such as Tim Delaney, Tony Baxter, and Pat Burke.

Many of Ray’s suggestions found their way into the design for the Orbitron and Phantom Manor at the park being planned for Paris. Ray didn’t ask to be paid for his ideas — Walt had already paid him handsomely by letting him raid the Disney vault. When Disneyland Paris (then known as Euro-Disneyland) opened in 1992, Delany dedicated the retro-futuristic Space Mountain to his heroes, Jules Verne and Ray Bradbury.

In 2007, in gratitude for Ray’s contributions, Disneyland honored him with a decorated oak tree in Frontierland, named after his 1972 fantasy novel The Halloween Tree. Ray flipped the switch to light Disneyland’s Halloween Tree for the first time on Halloween night 2007. It has shone forth every autumn since.

In 1981, Ray wrote an appreciation of his friend Walt Disney for the ten-year anniversary of Walt Disney World Resort—the place Walt first described to him over soup and sandwiches in 1964. Ray said:

We rarely think that just one man can shake and move a history of ideas and the world that grows from them.

But let us think the unthinkable.

What if Walt Disney had never been born? . . .

Walt and his bright noon fancies stand alone in a wicked world and say: “Let’s Do Everything Over and Do It Right.” Walt says terrible things like: Joy, Smile, or We Guarantee the World Won't End Tomorrow.

Through the eyes of Ray Bradbury, we catch a glimpse of the true measure of Walt Disney. It’s hard to imagine a world without Mickey Mouse, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, Disneyland, and on and on. The world is an infinitely richer, happier, more amazing place because Ray’s friend Walt Disney passed through it. Walt was—and will always be—optimism personified.

In the foreword to Howard and Amy Green’s Remembering Walt, Ray wrote, “Walt Disney was more important than all the politicians we've ever had. They pretended optimism. He was optimism. He has done more to change the world for the good than almost any politician who ever lived.”

The first time they had lunch together, Walt told Ray, “Nothing has to die.” Sadly, he was wrong. And paradoxically, he was right.

Jim Denney is a writer with more than 120 books to his credit, including the Timebenders science-fantasy series for young readers and a 2004 Disney biography which he co-wrote with Orlando Magic founder Pat Williams. Jim is a member of Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). He lives in California and blogs at WritingInOverdrive.com and at WaltsDisneyland.wordpress.com.