Celebrate Halloween weekend with Hallowscreen! our special selection of haunted cartoon shorts such as The Skeleton Dance, The Mad Doctor, Pluto’s Judgment Day, and more. You’ll have a “howling” good time. Costumes welcome! Saturday October 29th, Sunday October 30th, and Monday October 31st at 11:00am, 1:00pm, 3:00pm, and 5:00pm.

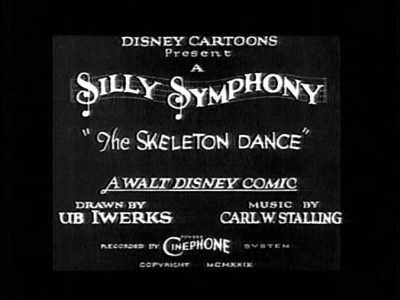

The earliest mention of Silly Symphonies is contained in two letters that Disney wrote his brother Roy and Ub Iwerks. The first, on 20 September 1928, indicates simply and idea for a “musical novelty,” some combination of music and animation. The second, written three days later, grows more precise. Stalling had pitched an idea for a film he called “The Skeleton Dance,” set in a graveyard, that would not only be a pilot, but also a template for a series built on comic dance routines and classical music. As Disney wrote, “Carl’s idea of the ‘Skeleton Dance’ for a Musical Novelty has been growing on me. I think it has dandy possibilities.” And by the time of the historic opening of Steamboat Willie at the Colony Theatre in mid-November, both Disney and Iwerks were busy working with Stalling to create their pilot.

It is not difficult to see why Stalling’s idea of “musical novelties” captured Disney’s imagination. It freed him from the restrictions of star personality. It also played to Disney’s early fascination with eccentric dances and music, eventually enabling him to work with free form ghost stories, legends, and fairy tales. But most intriguing, it provided the chance to break away from gag-centered cartoons in favor of atmospheric mood pieces. He thought The Skeleton Dance “would be dandy with all the effects poured in it.” He enthused over possible formal experiments: “I think we could cartoon the skeletons—and double print over a real background.”

It took Iwerks, working virtually single-handedly, the better part of six weeks to animate The Skeleton Dance at a cost of $5,485,40. And although the film was ready for release by early February 1929, it took Disney the better part of four months to find a major theatre willing to show it. Finally, amidst little fanfare, it opened at Los Angeles’ prestigious Carthay Circle Theatre.

The Skeleton Dance startled first night critics (by delicious coincidence it opened with Murnau’s latest Fox special, Four Devils); today it continues to astonish. Nothing in what survives in late 1920s American animation or in the earliest Mickey Mouse cartons prepares for the manic energy, rich atmospherics or inventive syncopated movement of Disney’s pilot.

Flash frames set the scene: black and white blank cels, alternating with frames of jagged white spikes drawn against black background create the lightning. Pulsating rings that open out in ever widening circles, then contracting as the camera appears to pull back, introduce the eye of a terrified owl who shivers and bristles while wavy branches hanging over him turn into menacing skinny arms and fingers. Vampire bats fly into camera from a church belfry, a gigantic spider with ferocious eyes plops into frame and then crawls away; and hound dog inflates and contracts as it bays against an enormous full moon. Snarling cats on top of matching tombstones spit out at each other.

Each image vibrates with kinetic energy that jolts the viewer to attention. This is Hallowe’en menace intended to delight as well as frighten. Disney had made some limited attempts to create mood in his silent films, but nothing like these extended nocturnal atmospherics. In fact, this is the first of Disney’s many attempts to turn night into a witching time rather than recycle familiar comic associations.

Then come the suave, effervescent skeletons. What marks them off from the prolog is the extreme frontality of their routines. Characteristic of late silent live action films The Skeleton Dance is designed to grab our attention in the opening sequence with its visual dynamism; striking angles, simulated camera movements, surprise elements dropping into the extreme foreground that are tricked up with last-minute metamorphoses. But, suddenly, the film settles down to the main event, which is presented in the style of a comic vaudeville routine—the entertainers playing direct to camera. A single skeleton quadruples itself behind a tombstone and four bodies present themselves to perform an eccentric dance. From The Skeleton Dance through The Clock Store, comic dances will define Silly Symphonies. During the first two and a half years, in fact, they—more than anything else—are what Symphony characters do. The anarchistic energy that critics from the 1970s found in the early Symphonies derives from this plotless, free-form structure. What The Skeleton Dance adds to the formula is the mystique of the witching midnight hour that gives a supernal atmosphere to the proceedings, puts time pressure on the unnatural entertainments (sunrise and the cock crow as the signal for revels to cease) and provides a link to a long, folkloric tradition. The midnight hour marking the time for toys, scarecrows, watches, statuettes, the supernatural, the dead and hieroglyphs to spring to life and caper continues as a controlling structure of the Silly Symphonies through the end of 1931.

Excerpted with permission from Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series by Russell Merritt and J.B. Kaufman. © 2006 La Cibeteca del Friuli.

J.B. Kaufman is a Disney author and film historian on the staff of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, and he has published extensively on topics including Disney animation and American silent film. He is coauthor, with Russell Merritt, of two essential reference works on Disney animation history: Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney and Walt Disney's Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series.

Russell Merritt teaches courses at University of California Berkeley in national cinemas, animation, and film styles and genre. He specializes in topics that cross disciplinary lines, and his current research interests include silent film, Japanese film (particularly Ozu Yasajiro), D.W. Griffith, animation, film and children's lore, French Film, German Film, and Disney's 1930s work. He co-wrote and was senior historical advisor for the Emmy-nominated series D.W. Griffith: Father of Film (directed by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill).

Calling all ghosts, ghouls, and witches—drag your bodies to The Walt Disney Family Museum’s Halloween Spooktacular—if you dare! In the Diane Disney Miller Exhibition Hall on Sunday, October 30, from 1:00pm – 4:00pm. Come dressed in your most horrifying ghoulish garb and scare up some fun at this frightfully festive event! You can buy tickets at the Reception and Member Services Desk at the Museum during regular operating hours (Wednesday through Monday, 10am-6pm), or online by clicking here.

Images above: A roster of animation heavy-hitters on the title card for The Skeleton Dance (1929). © Disney. 2) Ub Iwerks, Walt Disney, and Carl Stalling. © Disney. 3) © Disney.