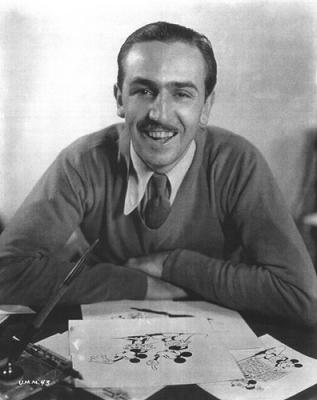

Have you ever wondered how Walt Disney learned about comedy? As Walt was growing up, he saw—and was inspired by—the work of the great silent screen comedians. On Saturday August 13 at 3:00pm, learn from Disney Authors and Historians J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt about how comics such as Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton influenced Walt's works in the program Comedic Influences with J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt. Tickets are available at the Reception and Member Service Desk at The Walt Disney Family Museum, or online at www.waltdisney.org.

The impact of silent film comedy on Walt Disney is inarguable. Throughout his career, the inspiration of Chaplin, Lloyd, Keaton, and their films can be seen over and over again. In turn, there were influences on Walt’s filmmaking that not only elevated the art, and added appeal top his characters, but brought new vernaculars to motion picture storytelling.

The impact of silent film comedy on Walt Disney is inarguable. Throughout his career, the inspiration of Chaplin, Lloyd, Keaton, and their films can be seen over and over again. In turn, there were influences on Walt’s filmmaking that not only elevated the art, and added appeal top his characters, but brought new vernaculars to motion picture storytelling.

The first of these “inspirations from innovation” was sound. “Quite consciously, I had been preparing Mickey and his screen pals for the advent of sound,” Walt recalled. “I'd made quite a few silent pictures prior to Steamboat Willie. It may seem a curious thing that even those in early films with their explanatory balloons [text titles that appeared on screen for dialogue], I had thought of them in terms of sound and speech, and dreamed of the day when the voice would be synchronized with the silent action. But I felt sure it was coming. Our tempo and rhythm and general animation technique were already being adjusted so that sound could fit in readily when it came.”

Not only did the addition of sound immediately enhance the Disney animated shorts; it heightened the comedy and “sold” gags that would never have had a place in silent cinema. Steamboat Willie is, in fact, all about sound. From the whistle of the riverboat to the impromptu concert played on the harried animal cargo, almost every key comedic moment in the film is derived from or punctuated by sound.

Music also underlies and carries through the entire film. Walt said, “For my medium it opens up unlimited possibilities. Music has always played a very important part since sound came into the cartoon.”

“As early as 1923, I was doing song films. I seldom thought out our silent product without some musical complement. I used to talk to the organist in the theater on arrangements before a film was shown. I even had a gadget that insured a crude kind of synchronization between the organ music and the picture action. In 1925, I had an animated cat in one of our silents direct the orchestra in the pit from the screen. While this was all preliminary to sound and film, it was preparatory background and equipment for that first Mickey Mouse talkie and the subsequent swift evolvement of sound.

Not just comedy, but character also resulted from sound. Walt said, “Of course, sound had a very considerable effect on our treatment of Mickey Mouse. It gave his character a new dimension. It rounded him into complete life-likeness. And it carried us into a new phase of his development.”

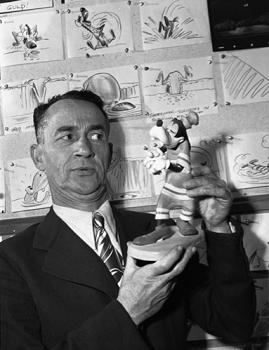

Some characters drew their comedy from sound. “Goofy came out the same way,” Walt said, “just as an incidental character that we used. And one of the boys I had over there who worked on the story with me and did sound effects, in fact, he was the fellow who put the thing on the end of The Three Little Pigs, Pinto Colvig. He had this “yuuuck, yuuuck” laugh, and I used it once just as a character in a crowd; I had a show going on onstage.”

Conversely, some characters drew their comedy from silence. “Dopey, he was always behind,” Walt said, “he couldn’t talk, and as we had Happy explain, ‘Well, he just never tried.’ I got voices for everybody, but we couldn’t find a voice for Dopey so we said, ‘Let’s let him be mute. We just won’t give him a voice. That will make him different.’ And it worked.”

The advent of Technicolor® also added to the comic arsenal of the Disney story teams. Now characters could have the blues, be green with envy, and see red—literally. “All of those kind of gags came with color. You see, when you see somebody like the wolf, when he blew, he blew until he turned purple. Like with sound came every kind of a gag you could do with sound, and after color you used it every way you could with color. Always putting rainbows in because you could do it.”

In later years, Walt’s interest in continuing to present the visually fantastic on the screen would inform—and be informed by—a number of technical innovations in special effects and cinematography; including a flying Model T and bouncing basketball team due to the inventions of an absent-minded professor, an English nanny with an elevating umbrella and a penchant for jolly holidays in chalk pavement pictures, or a mischievous phantom buccaneer who plays havoc with a track and field team.

Like most of Walt’s creative endeavors, his comedies were inspired by innumerable sources—and in turn inspired new directions, innovations, and inspirations all their own.

Throughout August, Walt Disney's 1962 live-action comedy The Absent-Minded Professor will be screened in our museum’s state-of-the-art digital theatre at 1pm & 4pm daily, except Tuesdays, and Saturday August 13.

Images above: © Disney. 2) Pinto Colvig's goofy guffaw created a character. © Disney. 3) A hiccup was Dopey's only "dialogue." © Disney.