“People still think of me as a cartoonist,” Walt Disney once said in his later years, “but the only thing I lift a pen or pencil for these days is to sign a contract, a check, or an autograph.” The laughter that must have come with this statement was no less grounded in truth. A talented illustrator at a young age, Walt had long since moved beyond producing drawings himself by the time he found success. He nevertheless remained an artist above all else, with an innate visual understanding of the world and an unrivaled sense of story. Another of his great talents was stimulating other artists, inspiring them to create stunning works of all types. Let’s explore some of this work by Walt’s staff, only recently rotated onto display in the museum’s main galleries.

David Hall was a masterfully prolific yet lesser-known talent on Walt’s team of inspirational sketch artists. Though he worked at The Walt Disney Studios for only fifteen months, he wound up producing hundreds of pieces of art between 1939 and 1940. As historian Didier Ghez describes, “Hall was way ahead of his time,” producing works grounded in a painterly style that transcended the usual confines of the animated cartoon, helping expand Walt’s vision of what his feature films could achieve.

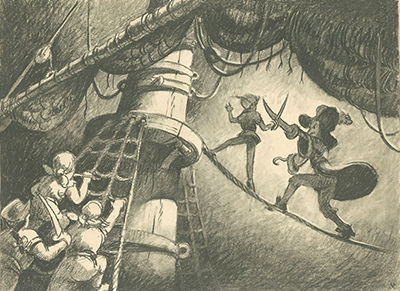

In this period of rapid development and expansion, Walt had greenlit multiple feature film projects, including Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953). Though most of Hall’s development was done on Alice, he also contributed a series of concepts for that beloved adventure in Never Land, two of which are now on display in Gallery 7. As an inspirational sketch artist, Hall was given time to explore the realms of visual possibility in his drawings, as Ghez writes, “It is on Peter Pan that Hall’s imagination really roamed free…” When films were often rigidly scheduled with a set production pace, this was a special opportunity for a studio artist.

A masterful watercolor depicts Peter, poised atop a large globe in the Darling house, turning to face an imposing portrait of a Naval captain behind him. He begins to grab his dagger in case the painting proves more than just a decoration. But the boy who refused to grow up is not back in Never Land just yet. The scene is beautifully composed with a busy, musky looking room of the Edwardian age. Light pours in from off-screen, highlighting Peter’s grace and movement. It is very much an animated painting.

Though projects like Peter Pan and Alice were ultimately delayed as financial difficulties and the Second World War took hold of the Studios, the kinship with the film to come is often striking. In another picture, a rarer work with charcoal, we glimpse Peter and Captain Hook locked in a duel amidst the pirate ship’s rigging. We think of that climactic battle from the final film, released over a decade after Hall finished his work. Walt never let a good idea fade away, and was able to pull on this cornucopia of art for inspiration in the years to come.

Lady and the Tramp (1955) was the first Disney feature produced in Cinemascope, a new and groundbreaking form of widescreen in cinema. “Thus,” as historian Leonard Maltin would write, “an added emphasis was given to the layout and design departments to create a succession of picturesque backgrounds against which the story could be played.” These expanded environments were an entirely new type of stage for Walt’s storytelling, and were created by an entire team of talented individuals supervised by art directors like Tom Codrick.

The background and cel-setup on display is from the memorable scene when Lady encounters the devious Siamese cats as they move throughout the home causing destruction and singing the now oft-quoted lyrics from “The Siamese Cat Song”, “We are Siamese if you please.” Strikingly horizontal in this wider format, the background gives us a “dog’s-eye-view” of the world, and its extended width allows the camera to move more freely across the setting. For Walt, it was yet another important tool with which to convey a story.

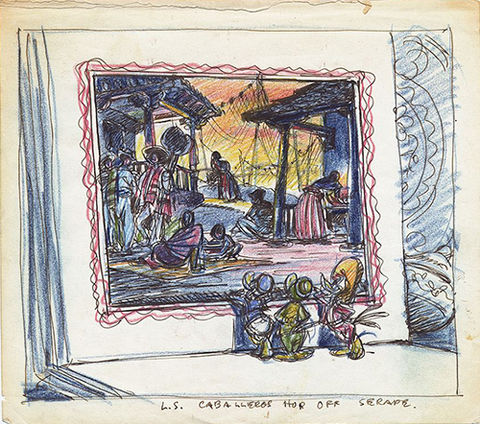

Other new works on display include a handful of story sketches for the Mexico sequence from The Three Caballeros (1945). Drawn by Ken Anderson, an incredibly versatile artist who could quickly dash out sketch after sketch, these drawings show Donald Duck, José Carioca, and Panchito on their magic carpet ride over the country, stopping in on local fiestas. Anderson’s style is loose and fast, common for story sketches. Yet still within the menagerie of scribbled lines one can glimpse a clear and precise form, accentuating the pose of each character, but still carrying a fluidity that yields potential. This all helped to further inspire Walt and the story team in their crafting of the narrative.

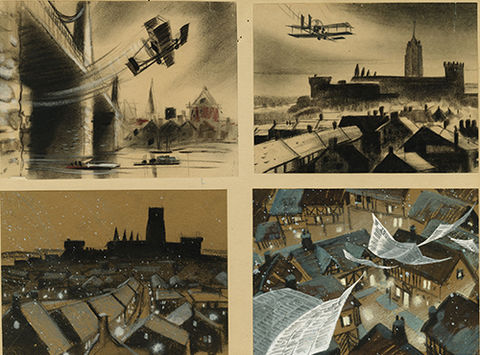

Another batch of new treasures are a series of concepts by Dick Kelsey for “The Wind in the Willows” sequence of The Adventures of Ichabod & Mr. Toad (1949). Kelsey, another lesser-known artist who joined the Studios during the boom of the late 1930s, had once been art mentor to master animator Ward Kimball. As essayist Vincent Randle describes, “The style [Kelsey] brought to the Walt Disney Studio was that of fine art, which happened to be the exact flair with which Walt Disney desired to imbue his animated features.”

Kelsey’s studies are atmospheric, depicting a moody London cityscape on the night of Toad’s escape from prison. Almost entirely in black and white, the staging is wonderfully cinematic and provocative. In one scene, the shadows cast from Toad’s prison cell bars are almost something out of film-noir. The resultant sequence in the film was certainly inspired by these concepts, along with two lighter drawings of Toad’s new airplane-crazed mania that ends the beloved story.

Though Kelsey’s work remains relatively unsung, he holds a special place in Disney history as one of the first artists whom Walt personally recruited to do drawings of his “Mickey Mouse Park,” which would ultimately become Disneyland. As Randle comments, “[Kelsey’s] ability to stage a scene with the proper use of color and scale certainly caught Disney’s attention. Walt knew that staging and color would play a vital role in the creation of his dream park.” Perhaps Walt recognized this innate ability of Kelsey’s in some of the concepts on display in the museum galleries.

“In this volatile business of ours, we can ill afford to rest on our laurels, even to pause in retrospect,” Walt would ultimately say. “Times and conditions change so rapidly that we must keep our aim constantly focused on the future.” And so this axiom of Walt’s was embodied in the spirit of every member of his artistic team. Artists like David Hall and Dick Kelsey never halted in their explorations of potential, producing painting after painting, drawing after drawing. Walt and his team never stopped moving forward. Like the trains that he so loved, the studio was constantly in motion, and with each puff of steam a new piece of art was born.

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.