Our consulting historians Paula Sigman-Lowery and Jeff Kurtti teamed up to provide this remembrance of another of Walt’s great collaborators.

A frequent analogy used in describing the creative collaboration of Walt Disney and his staff is that of a great conductor supervising and guiding every nuance of an artistically brilliant and technically outstanding symphony orchestra.

“Walt was an extraordinary man,” legendary animator and Imagineer Marc Davis said, “He looked at us not so much like we were employees, but we were people to create with—like a certain type of pencil.”

But Walt did not simply categorize his talents and use them in that single capacity, instead he looked well beyond their obvious gifts, seeing skills and aptitudes they frequently didn’t even know they possessed.

“He always asked you to do something that was far beyond what you thought you were capable of doing,” Disney Legend Alice Davis recalls, “and he always made you surprise yourself by reaching that goal.”

Disney matte artist Peter Ellenshaw agreed. “This was the essence of Walt. He made you feel that you could do it.”

Bill Justice, who passed away last week at the age of 97, had a lengthy and personal experience with Walt Disney’s team building, as well as his flexibility in identifying the talents of his team.

“He had a great facility to know what you’d like to do,” Bill said. “I refer to him as the greatest casting director. He would assign people to what they liked to do, and consequently got the best work out of them.”

Bill was quick to point out that this wasn’t limited to just artists, but extended to everyone, and to a variety of traits beyond artistic talents. “Walt’s casting eye included everyone at the Studio, not just the creative people,” Bill explained. “He tried to know everyone’s likes and dislikes.”

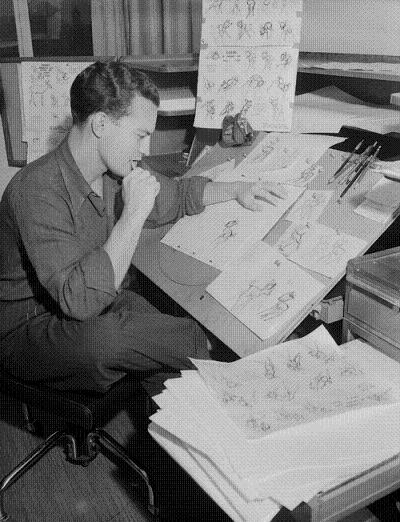

William Justice was born in Dayton, Ohio on February 9, 1914, and grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana. He attended the John Herron Art Institute on a scholarship, and studied to be portrait artist.

Bill began his Disney career in 1937 as an in-betweener, in one of the first of many professional surprises that awaited him. He was hired and sent not to work, but to art class with the legendary Don Graham.

“There were thirty of us in the class, and we had a class from eight in the morning to five, and a half-day on Saturday, and they paid us twelve dollars. After thirty days they hired twelve of us, and then we got to go to twenty-five dollars a week. But Don Graham taught the class, and then John Dunn taught us how to in-between, and right after the class was finished I got to work on in-betweens on Snow White for three months before it was finished. I got to do some in-betweens on the Queen, and a few scenes of the dwarfs.”

Bill recalled that learning the Disney system took time. “Everyone eventually wanted to be an animator, but moving up from in-betweener through breakdown man and first assistant was destined to be a lengthy ascent.”

By the time of Ferdinand the Bull (1938), Bill had “paid his dues.” “I moved into Woolie Reitherman’s room to become his breakdown man, then his first assistant…Even though the job hadn’t changed, being assigned to an animator was a big step forward. This was a great chance to learn.”

Recalling his first real contact with Walt, Bill noted: “I was working with Woolie at the time…and we were walking down the hall, and Walt came by to talk with Woolie, and he looked over at me and said, ‘Hi, Bill.’ I was surprised that he knew my name, and I was delighted to say hello to him for the first time.”

It was at this early point in his career that Bill began to sense the depth of Walt’s attention and involvement in both the work, and the workers at the Studio. “He met regularly with the story and gag men, and his input was made to them. So his thoughts filtered down to us this way. But he set the mood and each of us knew his standards.”

With the move to the new Studio in Burbank in 1940, there were more opportunities for Bill to develop his animation skills. “In 1941 there were two features in production at once—Dumbo and Bambi. Each had its own group. Since I was just getting established as an animator, I got to work on both pictures. Dumbo was a fun project. The story was easy to follow. The animation style was less complex with simpler backgrounds and more ‘cartoony’ characters. Unfortunately I only did a few scenes, mostly on Timothy Q. Mouse. You won’t see my name in the credits.

“Most of my time was spent on Bambi. My work on the ‘Pastoral Symphony’ section of Fantasia had given me the additional reputation of being able to do cute characters. I was lucky enough to do several scenes of Bambi and Thumper on the ice, plus scenes of Bambi and his mother in the thicket when Bambi woke up and said, ‘Mother, what’s all that white stuff?’ His mother replied ‘It’s snow.’ ‘Snow?’ And Bambi ran out and ploop, ploop, plop into a snow bank. I also did scenes of Bambi and Faline when they first met.

“Bambi gave me great personal satisfaction. Some of the best scenes I ever animated were in this picture.”

During this time, the divisive and destructive animator’s strike disrupted the Studio. But it seems not everyone really understood what was going on. “Yes, I have some strange memories of the strike,” Bill recalled. “One afternoon my assistant says, ‘Are you going to the union meeting tonight?’ And I said, ‘What union meeting? Never heard of it.’ There had been discussions, but I had never been in on any of them. The next morning I went to work, and here is a picket line around the Studio and I just looked ‘What the hell is this?’ I parked my car; I walked through the picket line, and went to work. There were rough times, and after a couple of days we tried to drive our cars in and park ‘em, and they would insult us and yell nasty things about us. But a lot of us went through the strike lines.”

The Strike probably affected Walt more deeply and personally than any event in his career, and forever afterward, he held a special loyalty for the employees that had stayed on the inside, Bill among them.

As World War II began, Bill, like so many of his colleagues, went from one assignment to another, with little sense of an institutional direction, but with an “all hands on deck” culture that he found enjoyable and stimulating. Bill remembered that they worked on, “…all sorts of odd jobs that came along at that time.”

He worked on dozens of the training and technical films the Studio turned out for the military, and famous shorts such as Der Fuehrer’s Face, Reason and Emotion, and The New Spirit.

Bill contributed to the Studio’s massive military insignia program, too. Walt Disney Productions created designs on request for both American and Allied military units, as well as civil defense and war industries. All of this work was done by the Studio free of charge, as a donation to the war effort.

“Hank Porter was about a six-foot-five man who worked over in the Shorts Building. He was designing insignias and had such an overload of work they asked me to help. He designed, I think, around a thousand insignias, and when I helped him, I think I did maybe 30 or 40 all together.”

During the War, a Studio VIP visitor led Bill to one of his most satisfying but least-known artistic efforts. Bill said, “When RAF Flight Lieutenant Roald Dahl came to the Studio…I was assigned to draw these little creatures according to his descriptions…Working together, he dictated the story and I made pencil illustrations for his approval. The December 1942 issue of Cosmopolitan featured his story with my illustrations, and it was quite a hit…This was the first time I’d ever been asked to create a new cartoon character…an artist named Al Dempster added some full-page color paintings to my illustrations and the book The Gremlins was published by Random House. It was the first book I’d ever illustrated. I loved those characters.”

Bill also visited military hospitals and did portraits of the servicemen, and sketched on their plaster casts. A “Disney Troupe” put on camp shows, and as Ward Kimball and his band (the Huggajeedy 8) played, Bill saw duty as “The World’s Fastest Sketch Artist.”

Bill expressed a sense of disappointment that he did not see “active” service during the War. “I had volunteered to be a combat artist. I had studied a lot in five years of art school, outdoor sketching and things, and I thought maybe I could do something like that. I was in good health at that time, playing a lot of tennis, and I was 1A all the time, but every time that my number would come up they would defer me. I never did go in. I guess they thought that what I was doing at the studio was important.

“But, you did whatever you were asked to do at that time.”

After the War, Bill served as animator on dozens of shorts, including Cured Duck, Old Sequoia, The Clock Watcher (1945), Chip an’ Dale (1947),Tea for Two Hundred (1948), Sea Salts (1949), Toy Tinkers (1949), Hook, Lion and Sinker, Lion Around (1950), Corn Chips, Out of Scale(1951), Donald Applecore, Pluto’s Christmas Tree, Trick or Treat, Two Chips and a Miss (1952), Working for Peanuts (1953), Grin and Bear It(1954), Beezy Bear (1955), and Hooked Bear (1956).

Bill became known around the Studio for his animation of Chip and Dale. He remembered that his wife Marie was “indirectly responsible for my favorite Chip and Dale short—Two Chips and a Miss. At the Ink and Paint Department’s Christmas gift exchange in 1951, Marie drew the name of a co-worker who loved Nellie Letcher, a popular song stylist of the day. The gal was so delighted with the records Marie got her she played them around the Studio. On a whim I took one to the Sound Department and tried it at a faster speed. The result was so cute we demonstrated it to Walt. He gave his blessing for a singing chipmunk cartoon. We invented a new chipmunk character, Clarice, as a female singer and the rest of the story fell into place. It was Clarice’s one and only appearance—the one time Chip and Dale had a girlfriend.”

Bill also provided character animation on The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1954).

Bill had many traits that probably appealed to Walt. He was clever without being showy, and his ideas were always about the improvement of the Studio output—not about his ego. He showed flexibility when being shifted between different roles on different projects, and most of all he was a loyal guy and team player—two very important attributes in the eyes of the boss.

In 1954, Bill was promoted to direct animation when Walt began producing animation elements for his television projects.

“The first thing I did was direct the opening of The Mickey Mouse Club, and my friend Jimmie Dodd did the music. I introduced Walt to Jimmie. X[avier Atencio] and I were working on a project about a pencil, and had Jimmie write a song about a magic pencil. When Walt heard it, he wanted to know who had written it and sung and played the guitar and that led to Jimmie getting the role on The Mickey Mouse Club.

“I am proud of that opening animation…X Atencio was working with me at the time and we decided instead of having a locale, to just have colored cards as backgrounds. This was a different thing, because usually there is a setting of some kind for cartoon characters to perform on. In this, they kind of performed in space. Walt filmed it in color [the program was broadcast only in black and white]. That’s how sharp he was, figuring he might be able to use it in the future.”

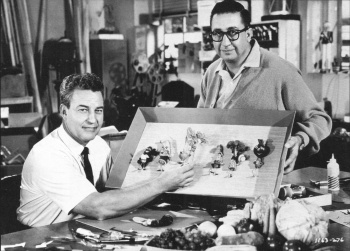

After a few years, Bill and X Atencio (along with T. Hee), moved into stop motion animation, a technique that had not been used at the Studio before.

“Producer Harry Tytle came to me on behalf of Walt and asked me if I could come up with a way to do Disney animation for less money,” Bill recalled. “So X Atencio and I came up with the idea of trying stop-motion. We made up some Indians and some rabbits and things for a test shoot and Walt liked the test.”

They created whimsical stop-motion films such as The Truth About Mother Goose (1957), Noah’s Ark (1959), and A Symposium on Popular Songs (1962), all of which were nominated for the Academy Award®.

The team created imaginative title sequences for The Shaggy Dog (1959), The Parent Trap (1961), and The Misadventures of Merlin Jones(1965).

After filming the title sequence for The Shaggy Dog, Bill and X found that the exposure was incorrect, and the entire sequence would need to be re-shot. He was nervous about telling Walt, not just about the expense but about the additional time it would add to the production. However, he told Walt it would have to be done—but that they could do it in three days (instead of five)—and that they would do it better. Walt told him to go ahead. Bill started to leave, when Walt called after him, “Give yourself and X credits for that title sequence.”

In addition to these title sequences, the team created elaborate and memorable stop-motion sequences for Babes in Toyland (1961) and Mary Poppins (1964).

“When I got into stop-motion stuff,” Bill admitted, “it was the hardest work I had ever done in my life.”

For “The March of the Wooden Soldiers” in Babes in Toyland, Bill remembered the mind-numbing technical complexity. “All stop-motion; and each soldier had 12 pairs of legs, and the march was on 12-beat…a march is about that fast… so each soldier had to change 12 legs. And you had to pick them up, pull them apart, put a different pair of legs on, and put them back in place…it took much concentration, keeping track of everything—mostly in my mind. We had a metal-top table, a big table, it had Formica on top of it, but each soldier’s feet were magnets…there’d be lines of them, like 40 soldiers—four in a line, and 10 lines. It would take, oh, five or six minutes to shoot one frame of film.

At this time, Walt brought Bill yet another unusual assignment, but one that would keep him busy for the rest of his Disney career.

Babes in Toyland was slated for a 1961 Christmastime release, and Walt saw an opportunity for additional publicity. They had done previous Christmas parades at Disneyland, but this time Walt went to Bill’s office with a more ambitious idea. “Why not have our own Christmas Parade this year, and we’ll build some giant toys and things? Bill, you’re going to do it!” Bill replied, “I am?”

He did, and with great success. Bill said, “The giant toys [from that first Christmas parade] worked so well it became my job to design the floats and costumes for the Christmas parades…and supervise their construction in Disneyland’s shops. Every year’s parade…was a challenge to add different units and improve the show.

“Walt said, ‘Bill, remember we’re not in competition with the Rose Parade,’ which meant he didn’t want the floats too big so the kids would lean back to see and fall over or something. I designed the toy soldiers, silly reindeer, snowmen, and more that are still used in the parades today. I worked on every Disneyland Christmas Parade from 1961 to 1979 when I retired.”

Bill also created the elaborate wardrobe for more than a hundred costumed characters to walk around the Park, a part of the Disneyland “show” that was of utmost importance to Walt.

Bill remembered, “Walt told me, ‘Other places can have thrill rides and bands and trains. Only we have our characters.'” The costumed characters were very important to Walt. He said, ‘Bill, always remember we don’t want to torture the people who are wearing them. Keep in mind they’ve got to be as comfortable as possible.’ The first concern was always safety and the second was accuracy.”

After nearly three decades at the Studio, Bill was reassigned. He looked fondly on his animation career, saying, “Walt Disney and the people I worked with at the Studio wrote the book on quality animation, I’d like to think I helped with a page here and there.”

Walt personally moved Bill to WED (now Walt Disney Imagineering) in 1965, in order to bring Bill’s skills and imagination to his newest animated characters: the dimensional Audio-Animatronics actors being created for Disneyland. To Bill, it made sense, “I had been an animator and involved in models and stop motion. Walt was planning these wonderful shows using Audio-Animatronics.”

“My first assignment was to program the Pirates of the Caribbean. I did the most sophisticated character in that show, which was the auctioneer. He had almost as many moves as Lincoln. I guess they figured if I could handle that one, then the rest of the figures would be simple. It took me six weeks to program the auctioneer. I had the scene of the auctioneer filmed in live action so I could use it as a guide.”

(On the side, Bill designed the City of Burbank float for the 1966 Tournament of Roses Parade, for which Walt served as Grand Marshal.)

In late 1966, Bill set up his auctioneer figure for Walt to review and approve. “Walt came in and saw the auction scene, and he checked everything out—including the chickens. He put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Good job, Bill.’ This was the only time he ever touched me, and one of the few times he ever thanked me in person. It was the last time I ever saw him.”

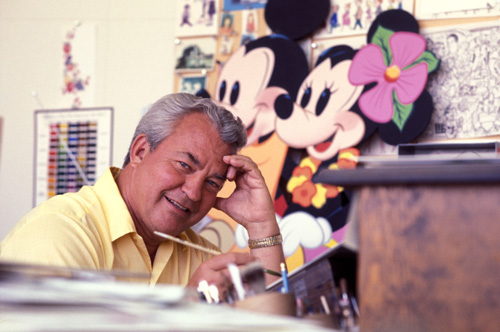

After Walt’s death, Bill continued his varied work all around the Disney organization—from specialty art and murals, to costumes and parades, to attraction and figure programming (he animated Lincoln for Disneyland, as well as Mission to Mars, Pirates of the Caribbean, The Haunted Mansion, Country Bear Jamboree, America Sings; and for Walt Disney World, Hall of the Presidents, and The Mickey Mouse Revue).

Even after his 1979 retirement, Bill continued to make appearances on behalf of the Company since he had such a rich Disney history; and was a charming raconteur, a genial gentleman, and still arguably “The World’s Fastest Sketch Artist.”

Bill was honored with ASIFA (Association Internationale du Film d’Animation)-Hollywood’s Winsor McCay Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1991, and his professional biography, Justice for Disney, was published by Tomart in 1992. Bill was named a Disney Legend in 1996, and there is a window on Main Street, U.S.A. in Disneyland that reads: “New Century Character Company, Custom Character Design and Parade Illuminations, Bill Justice – Master Delineator.”

Bill was always both grateful and somewhat awed by the man who had provided such an abundant, challenging, and varied workplace for himself and so many artists and creative people.

He remembered not some credit-hogging egomaniac, as many of the so-called biographies of Walt that appeared in the decades after his death averred, but rather a fascinating, complex, and especially a generous man.

“In the early 1960s, Walt was asked to do a one minute public service TV promotion for the Boys’ Clubs of America,” Bill recalled. “A script was written and approved by Walt…this script called for some on-camera drawing, but Walt hadn’t drawn in decades [so I] sketched what I thought would be the perfect solution: Walt would be at his desk talking about the Boys’ Clubs. Then he would rise, walk around to the front of his desk, grab a drawing pad and pencil, and begin to draw. At this point we would cut to my hands (wearing Walt’s jewelry) and I would make the drawings. Another cut to Walt, and he would show the completed work and finish the spot. Sneaky, but perfect.

“It was too sneaky. When we showed my storyboards to Walt, his first comment was ‘We’re not going to do it that way.’ Oops! Did I blow it? Then he turned to me. ‘It’s fine like we originally planned, except when I come around in front of my desk, Bill will be sitting at a desk behind me. I’ll introduce Bill, and he will make the drawings. At the end just cut back to me.’

“And that’s what we did. Walt introduced me on camera as his artist, we got an over-the-shoulder shot of me drawing, and there was no deception involved. The Boys’ Clubs were pleased, and this spot was used by all the major networks.”

Bill also remembered Walt’s curious and playful spirit that endured from the earliest days of the Hyperion Studio up to the very end of Walt’s life.

“Each March on Saint Joseph’s Day the swallows return to San Juan Capistrano,” Bill said. “Few people know they also return to the Disney Studio, making their nests in the metal awnings of the Animation and Ink and Paint Buildings. When I was animating I had a room at the end of the hall facing Ink and Paint. I could stand at my window, wave my arms, and the birds would swarm toward me. They must’ve thought I was a threat to their nests. Walt’s office was two floors directly above mine. Once I was in his office when we were interrupted by a phone call. While he was talking I walked to the window, waved my arms, and the birds appeared. This astonished Walt. ‘How did you do that?’ He tried and the birds came for him, too. Later I heard he repeated the gesture several times during the next few days.”

Most of all, Bill was grateful to have Walt’s regard. “Walt was good to me,” Bill said. “He was a very critical person and you had to do your very best to please him.

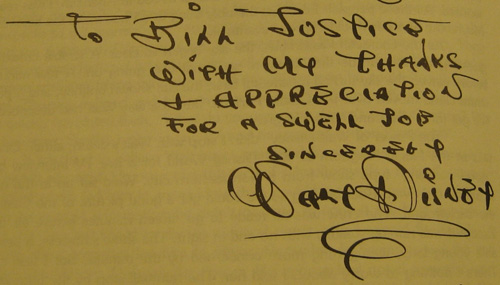

“I also got a ‘thank you’ note from Walt that I have saved all these years. ‘To Bill Justice—With Thanks and Appreciation for a swell Job. Sincerely, Walt Disney.’ It means a lot to me.”

Bill Justice (1914-2011)