With the surrender of Japan in September 1945, four years of brutal conflict for the United States during World War II finally came to end. It was at this time that Walt Disney refocused his efforts.

The studio lot had been requisitioned by the U.S. military shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and in the following four years, Walt devoted over 90 percent of The Walt Disney Studios’ output to the war effort.

Aftermath of the War and The Walt Disney Studios

Now, as the United States came out of the war, The Walt Disney Studios was in a difficult place financially. During the war, with so much of the Studios involved in the war effort, Walt could spare few employees to work on existing feature film projects. Development of films like Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953), which had been in the works since shortly after the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), ground to a halt.

In light of these circumstances, as the Studios looked to return to their pre-war state of operations—outside of commercial work and a few “packaged” animation films, like Fun and Fancy Free (1947)—there was not much on the table for Walt to work with. In fact, the Studios only managed to avoid losses in 1945 and 1946 through the domestic reissues of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio (1940).

The Solution to Survival: A Live-Action Film

Assessing his company’s current state of affairs, Walt recognized that in order to survive he would need to branch out and expand into new types of entertainment. One option he began to consider was making a live-action film. According to animation historian Michael Barrier, Walt had been considering experimenting in live-action “since as early as March 1941” when he thought about “making a wholly live-action film, based on Felix Salten’s The Hound of Florence.”

Five years after these initial thoughts, the perfect opportunity to begin such a project presented itself. After the war, Walt and Roy learned that over a million dollars of box office revenues that had been earned in England could only be spent in England due to new postwar policies implemented to revive their economy.

RKO Radio Pictures, The Walt Disney Studios’ distributor, likewise had a large sum of money tied up in England and offered to share in the production costs of a film. Walt initially thought about making cartoons in England. He soon realized, however, that training an entirely new staff of animators precluded the possibility of opening a cartoon studio on par with the one in Burbank. Instead, he set his sights on a live-action film to take advantage of the already-established film industry and infrastructure in England. Reflecting on the situation roughly a decade later in a 1956 interview with the Saturday Evening Post’s Pete Martin, Walt recalled:

“After the war we still had the frozen funds situation in Europe. So, in order to get the funds out of England, [RKO] wanted me to go to England and do something. The first thought was ‘Should I start a cartoon studio there?’ And I didn’t think I could because you have to train the artists for it or else import them […] I wanted to get into live.”

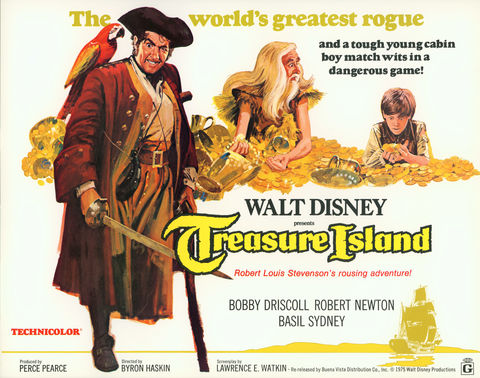

Disney's First Fully Live-Action Feature Film is Treasure Island

For the first of four films to be produced in England Walt decided upon a film adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel, Treasure Island, which follows the story of a young boy named Jim Hawkins as he searches for a hidden treasure. Not only did the film present what Walt believed would be “right for Disney to present,” but the book, whose author was a native of Scotland, also lent itself well to the array of actors England had to offer Walt and his team.

Walt sent Disney veteran Perce Pearce, who had been a writer on Fantasia (1940) and a story director on Bambi (1942), over to England to produce the film alongside fellow American Byron Haskin as director. The majority of the cast, with the exception of young American actor Bobby Driscoll who starred as Jim Hawkins, was comprised of well-known English stage and film actors.

Filming began at Bristol Harbour in Bristol, England, in July 1949. With production on Cinderella (1950) wrapping up, Walt occasionally flew to England to be involved in the film’s production. On one such trip he took his wife Lillian and daughters Diane and Sharon. Typical of his work ethic, Walt made the most of his time in England—Sharon recalled years later that, while there, he “was an all-day worker. He didn’t slow down at all.”

Walt was pleased with what he saw, and upon his return to Burbank following one of his trips, even poked a little fun at his animators. “Those actors over there in England, they’re great,” joked Walt to his animation staff, “You give ’em the lines, and they rehearse it a couple of times, and you’ve got it on film—it’s finished. You guys take six months to draw a scene.”

The Treasure Island Disney Movie Brings Peter Ellenshaw to The Walt Disney Studios

It was Treasure Island that brought English artist and future Disney Legend Peter Ellenshaw to the Studios. Ellenshaw—who studied matte painting under his stepfather, master matte and special effects artist W. Percy Day, O.B.E.—was contacted by the film’s Art Director Tom Morahan, who asked Ellenshaw if he was “interested in doing a ‘few’ mattes for Walt Disney.” In his autobiography, Ellenshaw recalled the impact it would have on his life:

“‘Maybe there would only be a few mattes,’ [Morahan] said, ‘Not worth your time.’ Not at all, I thought, to work for Disney even for a short while was certainly ‘worth my time.’ […] This was to change my whole life, and yet it seemed just a small job at the time.”

As production on the film progressed, the production team realized they were going to need a lot more mattes than originally intended, with Ellenshaw painting “forty or more mattes in [the] film.” Due to the large number of mattes required, Ellenshaw explained, “I had time to thoroughly understand the technique, so in the future I would be able to set up a department to do mattes in color at any studio.”

Following the success of Treasure Island, Walt returned to make additional films in England utilizing Ellenshaw’s matte work—including The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952), The Sword and the Rose (1953), and Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue (1954)—all starring popular British actor and future Disney Legend Richard Todd. It was during these early days that Ellenshaw developed his early impressions of Walt:

“Walt Disney would come to our small studio [in England] and spend time chatting with us about his life in films, he told many stories of his early years […] it was just like Walt to treat everyone on the same level. Later on, I was to discover that when Walt was at an important function in his honor, often he would be over in the corner of the room talking to the doorman or someone about the man’s outlook on life. Walt was the quintessential American, a firm believer in the common man.”

Treasure Island Leads to Other Disney Classics

Following the success of Treasure Island, Walt returned to make additional films in England utilizing Ellenshaw’s matte work—including The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952), The Sword and the Rose (1953), and Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue (1954)—all starring popular British actor and future Disney Legend Richard Todd. It was during these early days that Ellenshaw developed his early impressions of Walt:

“Walt Disney would come to our small studio [in England] and spend time chatting with us about his life in films, he told many stories of his early years […] it was just like Walt to treat everyone on the same level. Later on, I was to discover that when Walt was at an important function in his honor, often he would be over in the corner of the room talking to the doorman or someone about the man’s outlook on life. Walt was the quintessential American, a firm believer in the common man.”

In the decades following Treasure Island, Ellenshaw became a key artist at The Walt Disney Studios. During his time with Disney, he worked as a matte painter and special effects artist on classics including 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier (1955), and most notably Mary Poppins (1964)—for which he received the Academy Award® for Best Special Visual Effects.

The Success of Treasure Island

Upon its release, Treasure Island was a success for the Studios. It would go on to gross a box office total of $4.8 million worldwide on a $1.8 million budget. The film was particularly popular in Great Britain, where it was the sixth-most popular film at the British box office in 1950. Though production of the film used up all of the frozen funds Disney had in England following the war, the film’s success influenced Walt to return to England to produce more films. As recalled by Disney Producer, Screenwriter, and Disney Legend Bill Walsh in a 1973 interview: “[In England,] Walt discovered some of these great English actors like Peter Finch, Sean Connery, first. All made their debuts in Disney picture in little bits.” Indeed, Sean Connery, a legendary British actor, had his first leading role as Michael McBride in Walt Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959).

Of particular note in Treasure Island was Disney Legend Robert Newton’s performance as Long John Silver, the film’s main antagonist. Capturing the essence of what has become the quintessential film pirate, Newton’s performance was widely praised. Newton would go on to star in numerous similar roles.

The Significance of Treasure Island, Creating a Foundation For Future Films

It has now been over 70 years since Walt Disney’s live-action film adaptation of Treasure Island had its world premiere in London in June of 1950. Today, the film stands as a landmark feature for Walt, representing his first full-length live-action feature film. Yet, the film’s significance extends far beyond that.

During the nearly two decades following the film’s release in 1950 and spanning until Walt’s untimely passing in 1966, Walt would oversee the production of over 50 live-action films, including classics such as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Old Yeller (1957), The Shaggy Dog (1959), Pollyanna (1960), Swiss Family Robinson (1960), The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), and The Parent Trap (1961), not to mention Walt’s crowning achievement in the live-action and animated feature Mary Poppins (1964).

In many ways, Treasure Island helped lay the foundation for these later successes. It even served as an inspiration for many of the artists working on the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction for Disneyland Park. Disney artist and Disney Legend Xavier “X” Atencio, who penned the lyrics for the classic Pirates of the Caribbean attraction theme song, “Yo Ho (A Pirate’s Life for Me),” recalled in an interview in the early 2000s how, while conducting research for the attraction, he “got the Treasure Island film out […] to get the feeling of pirate jargon.”

Looking back, it could be said that Treasure Island marked the beginning of a swashbuckling new era of adventure and expansion for Walt and his eponymous company. An era that would take them into live-action movies, television, a theme park, and more!

– Parker Amoroso, blog contributor

Image sources (in order of appearance):

-

Treasure Island (1950) rerelease lobby card, 1975; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

-

Bobby Driscoll, Sharon, Diane, and Walt Disney stand by a camera on the set of Treasure Island (1950); c. 1950; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

-

Walt Disney and Robert Newton on the set of Treasure Island (1950); c. 1950; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.