Roy O. Disney once said, “Ub managed to solve a lot of problems for us.”

Ub Iwerks was a man of many talents. He was a prolific animator and a brilliant technical mind. He was Walt’s Swiss Army knife, a man who was to Walt whatever he needed him to be. He was as necessary to the beginning of Walt’s career as he was to the end. He left The Walt Disney Studios at a critical juncture to pursue his own career, but eventually found his way back to the company he had once animated into success to engineer it to new heights.

Ubbe Iwwerks was born on March 24, 1901 in Kansas City, Missouri. In 1919, while working at the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio, he met a young, ambitious artist who had just returned from World War I service in France with a knack for showmanship and a bold, entrepreneurial spirit. This artist’s name was Walt Disney. The two became fast friends and complemented each other’s skills well, as Walt would later recall, “He was very good at lettering and I did layouts…in pencil. Then I would turn it over and he would do the final inking and cleanup.”

When both Ubbe and Walt were laid off after the holiday rush and decided to go into a short-term venture of their own called Iwwerks-Disney Commercial Artists. They disbanded their fledgling company after a few weeks to take jobs with the Kansas City Slide Company—later renamed Kansas City Film Ad Company—where Walt discovered celluloid animation and started making experimental films of his own. Following another failed independent studio effort called Laugh-O-gram Films, Walt was encouraged by his older brother Roy and his Uncle Robert to leave Kansas City and get started elsewhere. The animation business was flourishing in both New York and Hollywood. Walt chose Hollywood. He persuaded Ubbe to follow suit, who eventually shortened his name to “Ub Iwerks.” The long-form version “Ubbe” clearly wasn’t Hollywood enough.

Walt secured a contract with Margaret Winkler of M.J. Winkler Productions, a New York distributor, with a Laugh-O-grams reel—the innovative live-action/animation combo Alice’s Wonderland—but the future of his new company was no more assured than the one that went bankrupt in Kansas City. Ub followed his friend regardless. Both Walt and Ub knew how important he would be to the process.

Following the successful run of the Alice Comedies, Walt moved on to his first all-animated series, “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.” Here Ub proved his loyalty to his boss and longtime friend in a major way. Charles Mintz, who had married Margaret Winkler and now was the head of Winkler Productions, was expecting a messy negotiation for the renewal of the Oswald series when he sent his brother-in-law, George Winkler, to arrange backroom deals with Walt’s staff. Mintz intended to secure leverage over Walt, planning to make the Oswalds without Walt in the event that he would not accept a pay cut. Ub did not sign with Mintz and attempted to convey to Walt the troubled waters ahead, but Walt believed nothing would come of it and blissfully arrived in New York to negotiate a modest raise owing to Oswald’s costs and popularity. He ended up leaving New York with his young company in serious jeopardy: with no distribution, no series—not even a character to their name. “DON’T WORRY EVERYTHING OK” he wrote in a telegram to Roy, trying to project confidence to his big brother, who would understandably be upset by being outhustled by Mintz. Ub Iwerks, the man Walt was “willing to put alongside any man in the [animation] business today” would provide the steady animation hand the Disneys needed to pick themselves back up.

Ub teamed up with Walt and another animator by the name of Les Clark to develop the earliest drawings of Mickey and Minnie Mouse—on display in our own Gallery 2B—and did the lion’s share of animating, backgrounds, and designing lobby posters for theaters exhibiting the early Mickeys. Ub could handle the heavy-lifting due to his legendary pace—an unheard-of 700 drawings a day! (According to Dave Smith’s Disney A to Z: The Official Encyclopedia: “Today a proficient animator turns out about 80-100 drawings a week.”) As the Studios expanded through the 1930s and into the 1940s, Les Clark would become a founding member of Walt’s Nine Old Men, his inner circle of key animators. Ub was on a similar trajectory. With his reputation for speedy and quality output, his name became “Ub”-iquitous in the animation sphere, as Walt once wrote to Lilly in 1929: “Every one praises Ubbs [sic] art work and jokes at his funny name. The oddness of Ubbs name is an asset in a way--it makes people look twice when they see it—Tell Ubbe that the New York animators take off their hats [to] his animation and all of them know who we are—”.

The trailblazing success of the third-produced (but first released) Mickey Mouse short Steamboat Willie (1928)—a cartoon in which Ub received a rare screen credit as an animator—and the films that followed gave Walt the financial flexibility to develop a new experimental series of cartoons without a central character: the Silly Symphonies. Ub animated through the first year of Sillies, and worked on the Mickey Mouse newspaper comic strips.

Creative differences with Walt wore on Ub and when offered the chance for artistic freedom and financial backing to run his own animation studio in 1930, he took it. Unbeknownst to Ub, this deal was through Pat Powers, one of the co-founders of Universal Pictures who had a complicated relationship (to say the least) with The Walt Disney Studios. Powers distributed and provided sound equipment for Disney’s cartoons starting with the seminal Steamboat Willie, but soon after, Walt and Roy became suspicious of his business practices and hired their first company attorney, Gunther Lessing, to protect themselves and satisfy their remaining obligations to him.

Where Powers was the saving grace for Mickey Mouse and The Walt Disney Studios in 1928, by the next year he was in the middle of a legal quarrel with Walt over box office receipts, and then the following year, he had signed away Walt’s best friend and animator and ceded the right to distribute Walt’s cartoons to his company’s parent distributor, Columbia Pictures. Upon learning of his new employer, Ub went through Roy to explain to Walt that he did not mean to take a job from Powers, and had he known who he would be working for, “he would never have gone into this.”

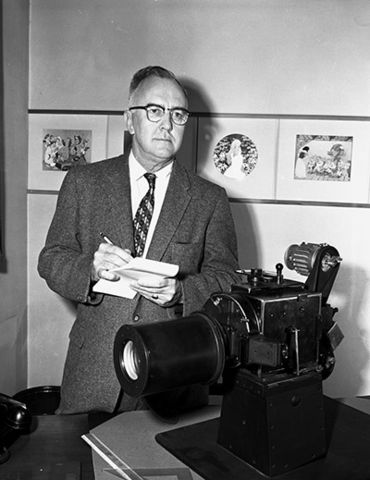

Despite Ub’s explanation, Walt felt blindsided by and took great personal anguish in Ub’s untimely departure. Ub sold his 20% stake in the company for under $3,000—which, if retained to this day, would have surpassed $4 billion, according to Walt biographer Bob Thomas. Ub’s studio was only moderately successful and folded in 1936. A decade after leaving, Ub would return to The Walt Disney Studios, but by that point he had already missed the period of its greatest growth in animation—innovating in color and personality animation, and making the ill-advised, but extraordinarily profitable jump from short cartoons to features with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Burying the hatchet (with the help of Pinocchio director Ben Sharpsteen), Ub returned to the Studios. He preferred not to animate anymore but rather serve in the technical effects department. Walt, the ultimate conductor of talent, acquiesced and found the perfect use for Ub’s technical wizardry. Ub’s first project was creating and eventually improving the multihead, aerial-image optical printer—one of which is on view in Gallery 9—refining the concept that got Walt his first film series back in 1923: combining live-action with animation. This effect was used to great effect in Song of the South (1946), Melody Time (1948) and So Dear to My Heart (1949). The optical printer was capable of combining and layering special effects such as title cards, matte paintings, filters, and believable optical illusions. According to camera technician Bob Broughton, this machine enabled Disney to create twins out of Hayley Mills (and Hayley Mills) for The Parent Trap (1961), green rolling hills for The Vanishing Prairie(1954), and animated penguins dancing with Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins (1964). Ub later developed the xerography process for animation, commonly referred to as Xerox, eliminating costly steps in the animation process by taking drawings directly from an animator’s pencil on paper to celluloid. Ub’s technical expertise gained him critical acclaim, winning him two Oscars and landing him a prestigious gig—special effects for Alfred Hitchcock’s production of The Birds (1963). Ub’s cinematic contributions reached its cultural zenith with George Lucas’ application of optical printing in 1977’s Star Wars.

New technological challenges brought on by the advent of Audio-Animatronics® required a steady hand with an engineering mindset, and Ub was all too happy to contribute. His fingerprints are all over “it’s a small world”, Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln, The Hall of Presidents, and early futuristic concepts for Walt Disney World. Sadly, Ub passed away nearly three months before Walt Disney World’s opening.

Ub Iwerks was one of the most consequential employees of The Walt Disney Company. Dave Smith, Chief Archivist Emeritus of the Walt Disney Archives, calls Ub “an animation genius, perhaps the greatest of all time.” His work ethic was admired by many; his talent denied by none. His inventions didn’t just “go through the motions,” they lived, breathed, “made the impossible possible,” and brought fantasies of tomorrow to a reality today. If the name “Ub Iwerks” finally rings a bell, he probably engineered it.

Chris Mullen

Marketing and Communications Assistant at The Walt Disney Family Museum