Wally Boag, who originated and played the role of Pecos Bill in nearly 40,000 live performances of The Golden Horseshoe Revue at Disneyland, passed away on Friday. He was 90 years old.

“I first ‘met’ Wally at my parents’ glorious 30th anniversary party, July 13, 1955, when he strode on stage at The Golden Horseshoe Saloon with his carpet bag full of gags. It was love at first sight. Like millions of others, including my dad, I never tired of his routine because he was always fresh. Dad loved The Golden Horseshoe Revue. He took all his guests from all over the world to see it, and they loved it. My dad really loved Wally, and those millions of others did too. He had a comic genius, and a wonderful stage presence that many younger comedians studied and emulated. He had a beautiful talent that he shared with all of us, and he was a kind, unpretentious man. We will never forget him.”

—Diane Disney Miller

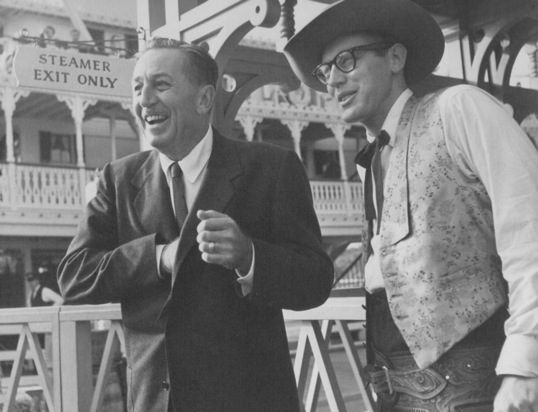

Walt and Wally Boag on the Riverboat Landing. © Disney

Wally began his Disney career with the opening of The Golden Horseshoe Revue in July 1955, and retired in 1982. After his retirement, he continued to assist The Walt Disney Company with special shows and events. Here’s his Disney story, in his own words, excerpted from an interview published in the Spring, 1993 issue of The E Ticket magazine.

“…in 1955, [Irish tenor Donald Novis, with whom Wally had worked in Australia] called me up. He said he was talking to Walt Disney who was going to open up a ‘little park’ out in Anaheim and there was going to be a ‘soda pop show’ …and he was looking for a comic. I went to the Studio and they sent me out to this empty set with just a piano player and a chair. Walt was sitting on the chair and he said: ‘Donald says you’re pretty funny … let’s see what you’ve got.’ So I had this bag, with a ventriloquist’s doll, and I did the balloon routine, and the bagpipes (a routine I picked up in Edinburgh in 1947).

“I finished with my dancing, and in those days (at the age of 34) I could do a flip-flop and a back flip and end with a bow. That’s how I got the job. On July 4, I signed a two-week contract, and we opened on the 17th. Walt booked Donald Novis (who already knew every song an Irish tenor could sing) and myself with ten solid minutes of vaudeville, already proven. He signed a girl singer who looked the part, and four Can-Can girls for the two dancing numbers. That was the show, with no extra writing except the special material for the girl. Walt was right there and he auditioned everybody. Walt’s idea was to have this 1871 Wild West vaudeville show with the Traveling Salesman comic and Pecos Bill, an Irish tenor and the dancing girls.

“The first show we did in The Golden Horseshoe…I think it was two days before the Park opened…was for Walt’s wedding anniversary. That was our premiere show, and there were quite a few important people in the audience. Hedda Hopper and Irene Dunne were there. It was mostly a dress rehearsal, but it was our first show as far as I’m concerned.

“…After my two week contract, I stayed on for about six months and they gave me a five year contract. When my second five-year contract came up, I hadn’t even realized it. Walt was in the box and he was with the Indian Chief and some of the Indians from the Indian Village. I had saved my ‘hair gag’ so that I could say, ‘All right…put down your hatchet…I’ll save you the trouble.’ I threw my hair down there in front of them…and Walt just fell about, laughing so hard. After the show was over, I went over and talked to him and he said, ‘By the way, you’re up for a new contract…don’t forget to ask for more money.’ You know, that was great."

“…Walt was great about calling me up and saying, ‘I’ve got an idea…listen to this.’ One morning he called me and said, ‘I’ve got a picture here…this guy invents something called Flubber…he gets some on the heel of his shoe…and I want you to come out and do a dance for a test, as if you had Flubber on.’ I went to the Studio and did the test, and it turned out that I did all of the stunt work for both pictures, The Absent-Minded Professor and Son of Flubber. That’s me doing all the jumping around, and I handled all the people doing the flying, like the basketball game. I supervised all of that. Mainly I handled Keenan Wynn, and he was concerned about the jumping. I did most of the single stuff myself, and I wore a special mask with his features…but as he jumps higher and higher, he still had to do close-ups and that’s a tough thing to do. In fact I broke my wrist during Son of Flubber.

“…I think it was in my second year at the Park that I got a call from Walt and he said: ‘I want you to work at WED [now Walt Disney Imagineering] as a writer…we’ll pay you for it.’ So I was on double salary at that point. I wrote a lot of stuff…jokes and things…for the Enchanted Tiki Room.

“I’m José…(squawk)…‘Buenos Dias Señors and Señoritas…stop talking while I’m squawking.’ That’s still my voice in there, and Fulton Burley is the Irishman. The Tiki Room was originally going to be a Chinese restaurant. The first that they worked on was a Mandarin, and a couple of comedy dragons on each side, talking and ad libbing. Walt decided that he didn’t want a restaurant. He wanted something that would turn over a little faster and be more fun all the way around. With the Tiki Room, I thought, ‘Gee, they’re never going to do this…’ And all of a sudden we did the reading and Walt said, ‘O.K., let’s do it tomorrow.’ The next day we got all the people together and we started taping.”

“…I did a thing called ‘Boag-aloons’ because of Walt. About six months into the show, I mentioned to Walt that when I was in England I put together a kit on how to make animals out of balloons, and sold them. He said ‘Why don’t you do that here?’ So I put the kit together and sold them at The Golden Horseshoe and I was making nice money, and it was Walt’s idea.

“…In 1965 they decided to name me the Director of The Golden Horseshoe Revue, and put me on salary instead of under contract like the other performers. From ’65 on I was salaried, which was nice, with stock options and so forth. I was involved doing gag and story writing, and stunt work for the films…because that was when Walt was alive. He didn’t mind ‘doubling in brass’ and you could wear many hats for him. Later on people would put you in a slot and you stayed there. Walt took advantage of people’s talents, tried combinations…knew what his people could do and gave them other chances.

“…The stage left box was Walt’s. If Walt was in the park they would notify us and that box (the one under the steer horns) would be kept empty…and he showed up a lot. He would always stay after the show and talk to us…

“…Back then, Walt was in the Park so much when nobody knew about it. He’d wear that blue blazer, an ordinary blazer and trousers, and no one would know who he was. I’d meet him in the Park sometimes when I was walking around seeing what was going on. One day, before Walt died, I went to see some construction going on near the Horseshoe. There was a lot of 2x4’s in there, and there was Walt, his wife and his grandchildren. He said, ‘Come on Wally, let me give you a tour…this is going to be my suite, and that’s Roy’s, and through here is going to be Club 33.’ And I said, ‘So long, Walt, thanks for the tour,’ and he died about four days later.

“…Walt was wonderful, in that if he told you an idea, he’d ask you to expand on it, and to do something different. Of course, if you did something too much different, he’d come back and say, ‘That’s not what I said I wanted…’ And you found out exactly where you stood.

“…I feel very lucky that Don Novis introduced me to Uncle Walt. Almost everyone who knew him called him that, because he was like a big uncle. He could be very demanding at times, but I found him very friendly. I loved to watch him at meetings because he’d get very enthusiastic about things. Walt understood very well that The Golden Horseshoe show was corny, but it worked. That’s what that show was all about.”

© Walt Disney Family Foundation. All rights reserved.

Our Consulting Historian Paula Sigman Lowery contributed to this article.