In 1942, Alexander P. de Seversky released his book Victory Through Air Power, in which he challenged the status quo of military doctrine with his argument that United States air power was weak, ineffective, and highly underdeveloped. He argued that military supremacy would be derived from air supremacy, and that the future of warfare rested on the development of a super fleet capable of strategic bombing or long-range air power. This, he argued, would be far more effective than tactical air power, in which aircraft only served in support of Navy or Army operations.

By the time his book was released, Seversky had developed a reputation as a troublemaker within both the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) and the Navy. In his book, he openly criticized the United States’ military leadership, and his claims that air power would make the Navy and Army obsolete were viewed as undermining the war effort by many in the armed forces. But the book was a massive success, and it was estimated that approximately five million people read the book.

Walt Recognizes the Potential of Victory Through Air Power

One of those copies found its way to Walt Disney after an employee, Eva Jane Kinney, brought the book to the Studios. Jane recalled in 1976 that, “Victory Through Air Power happened to be a Book of the Month [Club] selection during the war. I brought it to Dave [Hand]…and [he] wrote a […] memo on it for Walt.”

During a time when victory was anything but certain, Walt quickly saw the potential of Seversky’s ideas. In an interview with Pete Martin of the Saturday Evening Post for Diane Disney Miller’s two-part article “My Dad, Walt Disney,” Walt explained, “I read the book and I believed in air power…I just felt ‘Well gee, if they’re gonna go out and try to use battleships and all those other things, I just didn’t believe it would ever work.’” For Walt, the book “helped to clarify and crystalize my convictions, and I felt that the facts of air power contained in this book should reach far beyond the limited audience of the book-reading public.” With this in mind, he reached out to Seversky, and in July of 1942, he closed the deal to purchase the film rights.

Development of Victory Through Air Power

At the time of the film’s development, The Walt Disney Studios was already heavily involved in the war effort. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Army occupied the studio lot, where they would remain for several months. Soon after, Walt was contracting with the United States government and armed forces to create propaganda and training shorts, insignias, and educational films. By the time he decided to produce Victory Through Air Power (1943), he had already lost a number of his artists to the war effort, either via the draft or volunteering, and his resources—financial and otherwise—were stretched thin. But Walt felt the film was important, and he made the decision based on his personal patriotism, not his bottom-line. “I didn’t do it to make money, I didn’t do it to lose money. But I made it because I wanted to do it,” expressed Walt a decade later.

To get the job done, Walt placed some of his best on the project. Sequence directors included James Algar, who directed “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” segment of Fantasia (1940), Clyde Geronimi, a shorts director responsible for 1941’s Academy Award winning Lend a Paw, and Jack Kinney, known for his work as a director on Donald Duck shorts (Jack would also direct the 1943 Academy Award®-winning wartime short Der Fuehrer’s Face). Dave Hand, who directed both Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Bambi (1942), served as the animation supervisor. Disney Legend, animator, and member of the Nine Old Men, Ward Kimball remembered his role in the film fondly during an interview three decades later.

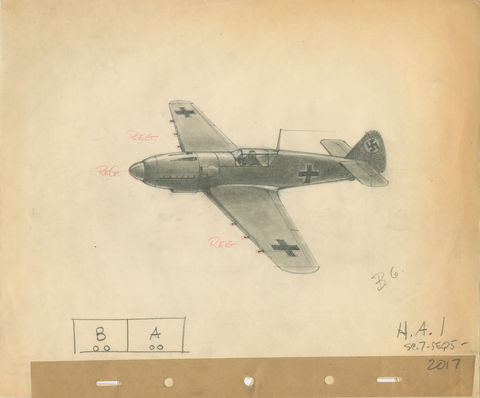

“On Victory Through Air Power I felt I was fortunate in having the most fun on the picture, because I got to do the historical stuff. I was fascinated with old airplanes. I’ve always loved old flying machines and I just thought it was a lark animating the first Wright Brothers’ flight, and the early battles between the German and French…I did a lot of authentic research.”

Other artists involved included Perce Pearce and Herb Ryman, who did story work, Dick Irvine, who worked as an art director, and Marc Davis, another member of Disney’s Nine Old Men, who worked on animation. Jack Kinney would later recall that “we had the best animators in the business on [Victory Through Air Power]”.

Rough Seas Ahead for Walt’s Film

The project wasn’t smooth sailing at first though. The USAAF and the Navy had been so infuriated by Seversky’s book that they felt compelled to launch a counter publicity campaign. When word reached them that Walt was planning on making a feature film out of it, their initial reaction was no different. Walt detailed his early interactions with the Navy regarding the film in an interview over ten years later.

“They said, ‘Now listen… you know what that’s going to do if you get that message over to the people—what it’s liable to do to the battleship program and our carrier program and things like that?’ […] And I said, ‘I just want to tell the story of air power’ […] And they had very serious talks with me. So I did modify the whole thing, because I did agree […] that aircraft carriers were vital at that time until they could be replaced with something else.”

A Partnership with the Navy and USAAF

Walt’s willingness to consider and work with the Navy and USAAF—something Seversky did not do for his book—played an important role in easing the minds of military leadership, even if they were still unconvinced by the arguments of the film. Most significantly, Walt completely removed any criticism of the branches—the most unsettling aspect of Seversky’s book in the eyes of USAAF. Vernon Caldwell, Walt’s Director of Publicity, screened the film on July 6, 1943 and noted to Walt, “We screened the picture downtown for five or six [United States Army] Air Force generals […and] other high-ranking officials (who applauded the picture at the end). They were most complimentary.” USAAF Brigadier General William Tunner wrote to Seversky after the release of the film: “I am so impressed with the message it carries that I have required all the officers of my headquarters to see it.” Now, instead of trying to counter the message of the book, the armed forces could be proud of Victory Through Air Power and use it to bolster their cause.

As General Tunner notes, the message of the film—the importance of air power and the will to fight on—is the key. Even though it is hard to say that the film had any measurable impact on military procedure or doctrine—military superiority solely through strategic bombing is impossible, even to this day—the film’s message undoubtedly inspired service members throughout the USAAF. The film, in many ways, captured the essence of American exceptionalism, encouraging the military and public alike to keep trying new things, to fight another day. It ultimately reassured its viewers that—just as the end of the film depicts the bald eagle triumphing over the Nazi octopus—America would win the war.

The Public’s Reception of Victory Through Air Power

In terms of the public reception, despite Walt’s best efforts to rush the production of the film—many of the Studios’ animators would later recall working into the late hours of the night on it—it ultimately missed the boat. “Victory Through Air Power had an awful lot of nice things, but it was probably too late,” suggested Jack Kinney. When Seversky’s book was published and Walt started production on the film in 1942, the outcome of the war was still shrouded in mystery, and, to an even greater extent, fear. However, with the Soviet Union’s triumph over Hitler’s Wehrmacht in The Battle of Stalingrad—which raged from late August of 1942 to early February of 1943—the inevitable outcome of the war became much clearer, even if it would take another two years to conclude. When the film was released on July 17, 1943, Americans were less consumed by fear and propaganda fatigue had begun to set in. Box office results were lackluster, and The Walt Disney Studios ultimately lost money.

Even in light of this, the film’s impacts should not be underestimated. In a time when movies tickets were around 25 cents, box office receipts indicate that well over 2.5 million tickets were sold. The critical reception was generally positive, with New York Times noting that “if Victory Through Air Power is propaganda, it is at least the most encouraging and inspiring that the screen has afforded us in a long time. Mr. Disney and staff can be proud of their accomplishment.” Further, in addition to its role in easing tension and boosting morale in the armed forces, both Walt and Seversky claimed that the film influenced President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s thinking on strategic bombing. Following Walt’s passing in 1966, Seversky wrote a piece in remembrance of him entitled Walt Disney: An Airman in His Heart. In the piece, he reiterated the claim.

“At the Quebec Conference in 1943, where plans for the invasion of Europe were formulated [the] combined Chiefs of Staff has reached an impasse. On one side were President Roosevelt and General Marshall, who advocated invading Europe on a certain day […] on the other side were American and Royal Air Forces, backed by [UK Prime Minister] Winston Churchill, who felt that the German Luftwaffe should be decimated before the invasion was attempted. Winston Churchill asked President Roosevelt whether he had ever seen an American film entitled “Victory Through Air Power” [sic]. The President replied that he had not […] The film [was] flown to Quebec at once. President Roosevelt and Churchill […] saw the film twice, after which they suggested that the combined Chiefs of Staff view it. After these showings […] the combined Chiefs of Staff decided to give the air forces the necessary priorities and freedom of action to guarantee control of the air before undertaking a European invasion.”

While Seversky is inaccurate in his claim that it inspired a pre-landing assault on the Luftwaffe—the conference was held in August of 1943 while the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) began in June—many of Walt’s colleagues reiterate his assertion that the film was screened for Churchill and others.

General “Hap” Arnold even came to like the film quite a bit. During the postwar demobilization—in a push to separate aviation from the army and establish an independent air force—he asked to borrow the Victory Through Air Power film script in “preparation of a speech to be delivered 5 November by a senior staff officer.” An independent air force would be realized with the passing of the National Security Act of 1947, under which the United States Air Force was made a separate military branch.

Though it was United States ground forces that would ultimately end the war during the Battle of Berlin from mid-April to early May 1945, it was the air supremacy of the AAF and RAF that had delivered many of the fatal blows to the Nazis in the waning years of the war. Through their patriotism and dedication to their country, Walt Disney and his staff could be proud that their films played an important part in America's contributions.

–Parker Amoroso

Image sources (in order of appearance):

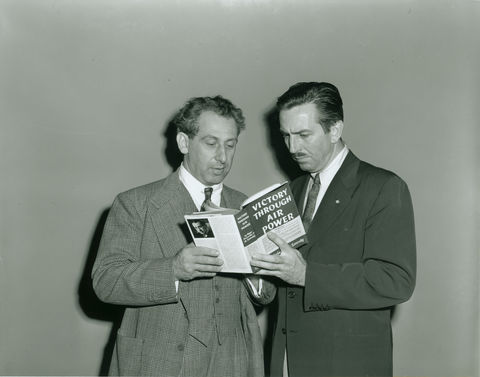

- Photograph of Walt Disney and Alexander de Seversky, c. 1943; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Disney Studio Artist, concept art, Victory Through Air Power (1943); courtesy of Mike and Jeanne Glad; © Disney

- Disney Studio Artist, background, Victory Through Air Power (1943); collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, gift in honor of Diane Disney Miller from the Glad Family; © Disney

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.