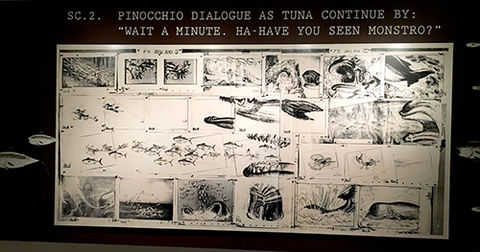

In accordance with Shark Week and our latest special exhibition, Wish Upon A Star: The Art of Pinocchio, this blog is all about another feared creature of liquid space. No, not the squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (sorry—I just swam right into that one). This is all about Monstro, the terrifying giant sperm whale that consumes Pinocchio, Geppetto, Figaro, and Cleo before sneezing them back out because Pinocchio, a character made entirely of wood, thought it prudent to start a bonfire.

Monstro—named after the Portuguese word for “monster”—traces his origins to Chapter 26 of Carlo Collodi’s original The Adventures of Pinocchio called “The Terrible Dogfish” (or Terrible Shark, depending on your preferred translation). The Dogfish is described as big as a “mountain” or “larger than a five story building,” which proved difficult for Disney animators to surmount (pun intended). As J.B. Kaufman, author of Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic, details: “Monstro compounded the usual problems of convincing movement in animation: here the movement must not only be smooth but must suggest the sheer geographic area covered by the whale.” What made Monstro such a “murderous adversary,” according to exhibition curator John Canemaker, is his capacity to feel (not to mention his malicious intent!). He was bad and he knew it.

Wolfgang Reitherman, one of Walt’s Nine Old Men and a man known for directing many of the later Disney films of Walt’s era, was given the task of cleaning up the rough work by Bill Tytla—already in charge of the imposing and volatile showman Stromboli—and animating what would become the monumental Monstro. This was an important collaboration, as Tytla’s departure following the animators’ strike in 1941 afforded Reitherman the chance to fill his role in animating intense characters and sequences. Reitherman was also responsible for the Slave in the Magic Mirror in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), and would later be in charge of animating the colossal battle between a Tyrannosaurus Rex and a Stegosaurus in “The Rite of Spring” segment of Fantasia (1940), the Headless Horseman chase in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” segment of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), and Maleficent in her dragon form in Sleeping Beauty (1959).

According to Bob Thomas, author of Walt Disney: An American Original, a Pinocchio story meeting in 1938 found an invigorated Walt bursting at the seams at the potential climactic scene unfolding in his imagination between Pinocchio, Geppetto, and Monstro:

“Pinocchio should use every ounce of force he has in his swimming to escape the whale. This should be built to terrific suspense. It should be the equivalent of the storm and the chase of the Queen in Snow White. . . .

We can get comedy out of the whale sneezing with Pinocchio and Geppetto inside. They should react in a certain way—it would be the equivalent to the hiccups in the giant’s mouth. The whale would quiver before the sneeze and shake them around, throwing them off their feet onto the floor. They would be shouting over the noise of the whale. When he sneezed, it would slosh the water all around, and up on the sides, and it would drop down on Geppetto and Pinocchio like a shower. The sneeze stirs the water up so when they escape, the water is already rough and stormy.

They get ready, and the sneeze blows them out. Then as the whale comes into another sneeze and the inhale starts drawing them back, they have to paddle hard against it. . . .

The underwater stuff is a swell place for the multiplane, diffusing and putting haze in between, with shafts of light coming down. I would like to see a lot of multiplane on this.”

Walt’s commitment to utilizing the most sophisticated technology at his disposal for Pinocchio’s many effects-driven sequences is evident in the final product. Sparing no expense, Pinocchio would go on to be arguably—according to a 1940 review of Pinocchio in The New York Times—“the best thing Mr. Disney has done and therefore the best cartoon ever made.”

On Saturday, July 30th, The Walt Disney Family Museum is hosting a talk called “The Myth of Monstro and Other Whale Tales” featuringguest speaker Adam Ratner from the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, CA. Wish Upon A Star: The Art of Pinocchio, brought to life by guest curator, John Canemaker, is a special exhibition on view until January 9, 2017.

Chris Mullen

Guest Experience Associate at The Walt Disney Family Museum

Sources

Collodi, Carlo. Pinocchio. Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 1995. pp. 118-119.

Collodi, Carlo. Pinocchio. Translated by E. Harden. London: Puffin, 2011. p. 150.

Kaufman, J. B. Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic. San Francisco, CA: Walt Disney Family Foundation Press, 2015. pp. 89-90, 97, 99.

Canemaker, John. Wish Upon A Star: The Art of Pinocchio. Special exhibition. The Walt Disney Family Museum, 2016. Text.

Thomas, Bob. Walt Disney: An American Original. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976. pp. 123, 149.

Folkart, Burt A. “Wolfgang Reitherman, 75: Disney Animator Dies in Car Crash.” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1985. http://articles.latimes.com/1985-05-24/news/mn-17061_1_1_wolfgang-reithe....

Nugent, Frank S. "'Pinocchio,' Walt Disney's Long-Awaited Successor to 'Snow White,' Has Its Premiere at the Center Theatre--Other New Films." The New York Times (New York City), February 8, 1940, The Screen In Review sec. http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9a03e2d8113ee33abc4053dfb466838b...