As the 1960s came into view, Walt Disney continued to double down on the Disney Studios’ foray into live-action, which began a decade earlier with 1950’s Treasure Island. In particular, he made Fred MacMurray a central figure in Disney’s live-action comedies.

In 1959, MacMurray starred in The Shaggy Dog, which despite a small budget turned out to be a massive box office hit, becoming the second highest-grossing film of the year (indeed, the film beat out cinematic classics like Rio Bravo starring John Wayne and Dean Martin as well as The Nun’s Story starring Audrey Hepburn).

Despite starring in the film and providing it with some of its most humorous moments, MacMurray’s role was rather limited, with far less screen time than Tommy Kirk, Tim Considine, and Kevin Corcoran. MacMurray reportedly complained during its production that the comedic police officers in the film had more vibrant material than him. Many critics felt differently though—Variety praised MacMurray’s performance, noting, “Where MacMurray has a good line, he shows that he has few peers in this special field of comedy.”

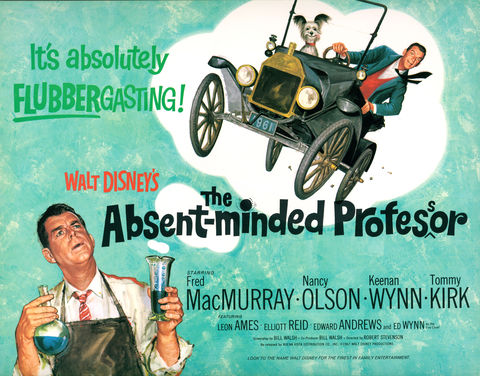

Walt felt MacMurray’s performance had been great and wanted to find a way to use him again. When the Studios decided to use the black-and-white comedy film model again in 1961 with The Absent-Minded Professor, MacMurray returned for a far more lively and well-rounded role as Ned Brainard, a professor of physical chemistry at the fictional Medfield College of Technology. Producer and screenwriter Bill Walsh, who also produced and co-wrote The Shaggy Dog, came on as the sole writer of the film. He later remembered that “[Walt] loved [MacMurray] as a comedian. After The Shaggy Dog, Walt looked for another vehicle for [him]. The idea of The Absent-Minded Professor came to him.”

Where [Fred] MacMurray has a good line, he shows that he has few peers in this special field of comedy.

MacMurray himself had been a well-known leading actor in Hollywood since the mid-1930s, with his most renowned role coming in the 1944 film noir Double Indemnity, written and directed by Billy Wilder. However, it was his late 1950s and 60s roles with The Walt Disney Studios that would cement his image as the quintessential American father figure—not entirely different from the persona Walt had established through his Disneyland television show and its later iterations, including Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. Prior to that time, MacMurray’s career had seen a decline, and the success of The Shaggy Dog rejuvenated his image and status as a box office star. And MacMurray was comfortable working for Disney. He later recalled how “There’s a lack of tremendous pressure in the Disney Studios […] It’s a pleasant place to be." Similarly, much of the studio staff found MacMurray easy to work with given his breadth of experience. Arthur Vitarelli, who worked on both The Shaggy Dog and The Absent-Minded Professor as an assistant director and second-unit director respectively, explained in a 1989 interview that MacMurray was “very professional, on time, knows his script, everything—just a most professional guy.”

Outside of MacMurray, the film featured a number of other long-time actors, many of whom had worked with the Disney Studios previously. Tommy Kirk starred alongside MacMurray once again, this time as Biff Hawk, the son of Alonzo P. Hawk, a ruthless businessman and the main antagonist of the film. Kirk had been a mainstay at The Walt Disney Studios since the mid-1950s, starring in live-action features such as Old Yeller (1957), The Shaggy Dog (1959), and Swiss Family Robinson (1960). Nancy Olson, best-known for her work in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), played the role of MacMurray’s love interest, Betsy Carlisle. This marked Olson’s second role in a Disney film, following her portrayal of Nancy Furman in 1960’s Pollyanna. Coincidentally, MacMurray had turned down the lead role in Sunset Boulevard, where he would have starred alongside Olson and Gloria Swanson.

Father and son Ed and Keenan Wynn also appeared in the film, with Keenan playing Alonzo Hawk and Ed bringing to life a small comedic role as a fire chief at the end of the film. Ed Wynn, of course, had provided the voice of the Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland (1951) and was a favorite actor of Walt’s. Robert Stevenson, the film’s director, was quite fond of him as well. Stevenson was well-known for his insistence on sticking to the script, but he operated under a different set of rules with Ed Wynn. “I wouldn’t let anyone interrupt him […] I just let him go on and on. You see, he had the most wonderful imagination,” recalled Stevenson. Ed Wynn and Stevenson went on to work together again in Mary Poppins (1964) just a few years later.

Working from the same formula that had produced The Shaggy Dog, Walt turned again to Bill Walsh for the script. For inspiration, Walsh—who later would write the screenplay with Don DaGradi for Mary Poppins—used material to which Walt had bought the rights some years earlier. In a 1968 interview, Walsh recalled, “Sam Taylor had written some ‘Letters to the President’ in Liberty Magazine. There were several—one about a rubber device, another about a flying car, and a third something about milk. Walt had bought the stories a long time ago and it was an old idea that came back to him. He adapted what he had bought for his current needs.” Robert Stevenson, who during the course of his career directed 19 Disney films including Johnny Tremain (1957), Old Yeller (1957), Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959), Mary Poppins (1964), and The Love Bug (1969), recalled Walt’s vast archive of stories in a 1975 interview: “Incidentally, one interesting thing about Walt was that whenever the Studio was short of a story, somewhere in a back pocket he had a story he’d had for 20 or 30 years. The Absent-Minded Professor […] is a story written during wartime. Walt held that one for fifteen years,” remembered Stevenson.

The film made use of some of the company’s other top talents as well. George Bruns, for example, wrote the score. The film also marked the first appearance of a Sherman brothers’ song in a Disney feature film. The two brothers, Richard and Robert Sherman, provided the catchy “Medfield Fight Song” that opens the film. The two famously went on to write the music for Mary Poppins and The Jungle Book (1967), as well as numerous other Disney pictures and attractions.

Incidentally, one interesting thing about Walt was that whenever the Studio was short of a story, somewhere in a back pocket he had a story he’d had for 20 or 30 years. The Absent-Minded Professor […] is a story written during wartime. Walt held that one for fifteen years.

At the time of the film’s production, Walt—who now had hundreds of projects in motion—was no longer involved at the same level in the company’s films as he had been in decades past. Instead, he tended to play more of a supervisory role in order to keep tabs on everything going on. Even so, his opinion was still actively sought after by Bill Walsh. Walsh explained in a 1970s interview with Bob Thomas that, “If I could manage to amuse him, he would supervise and come in and help… I had a secret trick… I always stuck a little bit of Walt in the main character. So, he could recognize himself… in [The] Absent-Minded Professor, I’d give him some of Walt’s own personal characteristics.” It’s no wonder Disney songwriter Richard Sherman noted years later how “[Walt] identified with the characters Fred played—he was the absent-minded professor…[Walt] was always experimenting.” Of course, Walt remained a big-picture person, an approach that meshed well with Walsh’s role: “Walt had the basic elements floating around inside his head. He was thinking of everything: promotion, television, ‘Is it a story that can be sold on television?’ ‘Is it suitable for American audiences and not foreign?’ He could stand far back and look at the whole thing while I would be face-up against the story.” And, of course, Walt continued to emphasize the things that made the Disney brand so strong. In reference to the popular basketball scene in the middle of the film where Professor Brainard puts his incredibly bouncy flying rubber compound, dubbed “flubber,” on the players’ shoes, Walsh explained how “no other studio was doing movies relating to sports, but Walt saw this was our kind of audience: kids, teenagers, the family.” As such, Walt continued to dial in on the core demographics eager to see his movies.

While it is true that Walt had moved into a more supervisory role than he once had, he was still far more involved in the details than producers at other movie studios. Robert Stevenson, in particular, enjoyed working for Walt due to his unique style:

“Directing for Walt was interesting because, certainly for the pictures I worked on, we worked much more thoroughly and much more creatively on the script than any other producer I’ve worked for. He would really be doing an awful lot of writing, even though he didn’t put it on paper […] This [was] in conference. And the extraordinary thing is, the moment the picture started shooting, he would leave a director entirely alone. When he came on the stage, he would be in the back chatting to who was around. He never gave any instructions during the shooting of a picture. But he would then come back very solidly in the editing. He was a magnificent editor. He had a great sense of how much, or long, a scene is worth.”

This unique approach gave Walt the ability to remain involved and invested in each of his films, but still enabled him to juggle the many things going on simultaneously at the company. According to Stevenson, where Walt shined was in story conferences before shooting. “He had the most peculiar quality I’ve ever known anybody to have: When he read a script, he never saw the words. He saw the finished picture, in a way no one can […] I wish I could do that […and] he had a fantastic memory. We might get to the third version of a script, and he’d remember a line in the first version we left out,” explained Stevenson.

—Parker Amoroso, blog contributor

Image sources (in order of appearance):

-

Lobby card for The Absent-Minded Professor, c. 1974; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, © Disney

-

Ed Wynn on the set of The Absent-Minded Professor, c. 1961; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library, © Disney

-

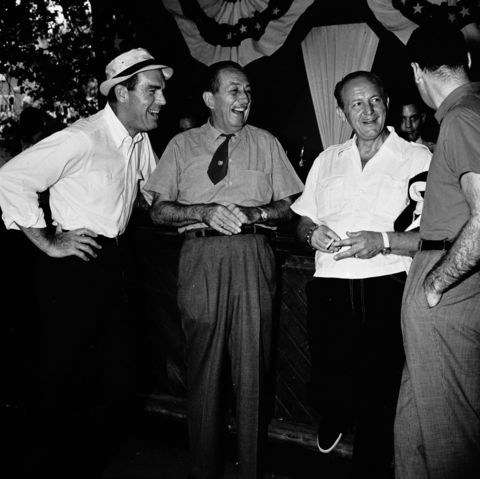

Fred MacMurray, Walt Disney, James Neilson, and Elliott Reid at Golden Oak Ranch, 1961 ; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library, © Disney