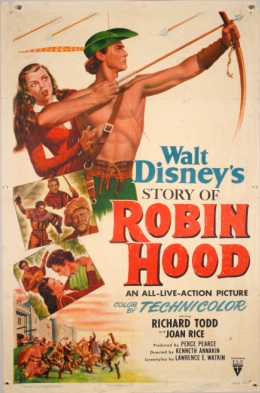

May at The Walt Disney Family Museum features Walt Disney’s screen treatment of the Robin Hood tale, one of several films that Walt adapted from popular works of legend, literature, stage, and screen. Walt Disney’s The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men screens daily through May at 1:00pm and 4:00pm (except Tuesdays, and May 5 and May 19). Further program information and tickets are available at the Reception and Member Service Desk at the Museum, or online by clicking here.

“It’s always a challenge bringing a great story classic to the screen,” Walt Disney once said, “giving visual form to characters and places that have only existed in the imagination. But it’s the kind of challenge we enjoy.”

“It’s always a challenge bringing a great story classic to the screen,” Walt Disney once said, “giving visual form to characters and places that have only existed in the imagination. But it’s the kind of challenge we enjoy.”

Typically, however, the stories Walt brought to the screen did not exist only in the imagination, but were his own versions of stories that were established classics of literature—or even already-popular stage plays or movies.

Certainly, fairy tales had been a staple of filmmakers since the beginning of the medium, and Walt’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs had been inspired by his attendance, as a young newsboy, at a 1916 screening of the Famous Players silent film version of the story.

Pinocchio was adapted from an Italian children’s book that enjoyed a wide American popularity in a 1911 English-language edition (one wonders if a 10-year-old Walt read a copy of that Everyman’s Library printing); Bambi was an Austrian novel that was published in America in 1928. And so it was for most of Walt Disney’s output, with the notable exception of much of Fantasia (1940), Saludos Amigos (1942) and The Three Caballeros (1945).

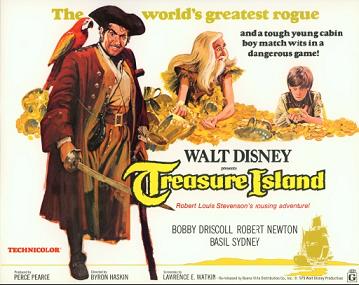

Walt’s first full live-action film was his 1950 adaptation of Treasure Island, which had been produced by MGM as a feature for stars Wallace Beery and Jackie Cooper in 1934. (Disney veteran Joe Grant remembered that Walt had originally pondered Treasure Island as an animated feature in the late 1930s!)

“After the war we still had the frozen fund situation in Europe,” Walt recalled. “So, in order to get the funds out of England, they wanted me to go to England and do something…I had this story, Treasure Island, I wanted to do, and I suggested we go over and do Treasure Island—and that way we’d use our funds.”

The successful financial strategy and box-office popularity of Treasure Island led to the production of three similar films in England, the first being a retelling of the Robin Hood legend—which had already been a smash hit with Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland for Warner Bros. in 1938 (the others were The Sword and the Rose and Rob Roy: The Highland Rogue, both released in 1953).

There has been frequent puzzlement as to why Walt would risk re-making such films—so recently-released, popular, and critically well-regarded. First, film in those days was a transient medium; there was no television, no home video—and the theatrical re-release of older films was only regularly practiced by Walt Disney Productions. For a large segment of the audience, these were simply familiar tales, and a majority of the potential audience had never seen any film version of the stories.

There has been frequent puzzlement as to why Walt would risk re-making such films—so recently-released, popular, and critically well-regarded. First, film in those days was a transient medium; there was no television, no home video—and the theatrical re-release of older films was only regularly practiced by Walt Disney Productions. For a large segment of the audience, these were simply familiar tales, and a majority of the potential audience had never seen any film version of the stories.

Director Ken Annakin recalled that in creating the production entirely in England, Walt had a great desire for authenticity rather than the glossy Hollywood Technicolor® of the Warner version “In the planning of our picture they were very, very determined that ours should be very, very true,” Annakin said. “We went up to Sherwood Forest, we went up to Nottingham, and the script was written as accurately as it could be there, from all the records. And so I thought we were probably making a truer picture than had been made before.”

Annakin also felt that Walt assembled a team he felt he could trust. “I remember him on that picture having set the overall key of what he wanted, and seen that it was going the way he wanted—he trusted Perce Pearce as the producer. He came to trust me as the director, and I must say, I have never had Walt ‘looking over my shoulder’ at anything.”

“He had a great, great trust in Carmen Dillon, who was responsible for the historical correctness of everything from costumes to sets to props.” Annakin recalled. “I’m not sure why he was so certain, but he was dead right for having chosen her…and his reliance was one hundred percent.”

“He had a great, great trust in Carmen Dillon, who was responsible for the historical correctness of everything from costumes to sets to props.” Annakin recalled. “I’m not sure why he was so certain, but he was dead right for having chosen her…and his reliance was one hundred percent.”

Walt also relied heavily on an animation technique that had not yet become commonplace in live-action filmmaking: the storyboard. “I had never experienced sketch artists, and sketching a whole picture out,” Annakin said. “That picture was sketched out, and approved by him—but it was designed in England, and sketches were sent back to America.”

For all his influence and control, Walt was not an overbearing studio head in Annakin’s view. “Basically, he visited the set maybe half a dozen times, stayed probably two or three hours while we were shooting,” Annakin said. “I remember that he used to go off to a place very near Denham where we were shooting, he used to go off to Beaconsfield and spend hours with a guy who had the best model railway, I think in the world.”

The director, later visiting Disneyland, remembered Walt’s trips to Beaconsfield, and wondered if he wasn’t already deep into his ideas and dreams for his new park.

But in the end, Annakin never wavered from his understanding that the film he was making was, even with his own directorial expertise and perspective, and an insistence on a more authentic telling of the Robin Hood story, a Walt Disney production.

“I mean, he was making his picture,” Annakin said, “his version, and I think we came up—with Walt’s help and insistence on truth and realism—we probably were as near as makes any matter.”

On Saturday May 19 at 3:00PM, director (The Iron Giant, Mission: Impossible/Ghost Protocol) and two-time Oscar®-winner (The Incredibles, Ratatouille) Brad Bird will discuss how Walt adapted well-known and even previously-filmed stories and created what are widely regarded as “definitive” versions. From Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men; Treasure Island to Swiss Family Robinson, Bird will explore the appeal of these tales to Walt-and how his individual and personal viewpoint made them enduring classics.