The Walt Disney Family Museum has made some exciting new additions to gallery 3. All new Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs artifacts are now on view to showcase various characters, animation art, and merchandise. Enjoy excerpts from The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: The Creation of a Classic, both by J.B. Kaufman, celebrating the new rotations now on display.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

As if the very idea of a feature-length picture were not challenging enough, Walt’s selection of the story of Snow White automatically compounded the difficulty of his project. The character at the center of the story, the character around whom most of the action would revolve, was not a simple, broadly caricatured, “cartoony” character, but a delicate, feminine creature. And she was a human being.

Snow White’s dancing scenes in the party sequence were among the most challenging for the animators. As with most other sequences, live-action reference footage was filmed as a guide. These photostats represent the scenes in which Dopey climbs on Sneezy’s shoulders to form a composite figure, nicknamed “Dozey” by the artists, as a dancing partner for Snow White. Marjorie Belcher, in costume, performs Snow White’s actions, while sequence director Perce Pearce stands in for artificially tall partner. These six photostats were, of course, part of a much longer series of images, which the artists used in order to study and analyze the dancing action. Similar reference footage of some of the dwarfs—played by studio staff members and, at some sessions, by burlesque comedian Eddie Collins—was also filmed, simply to suggest possible attitudes and actions for the animators’ benefit. On at least one occasion, Marjorie Belcher donned loose, floppy clothing and impersonated “Dozey” himself.

Development of the Entertainment sequence occupied the better part of the film’s four-year production, as these images attest. [To the left] is one of the earliest sketches of the part, submitted before the personalities of the dwarfs had been clearly defined. In between, literally hundreds of other sketches and paintings had suggested the details and the general atmosphere of the sequence, as in the representative example.

Production of Snow White brought remarkable artistic growth. As Walt insisted on ever higher standards of technique for his feature, studio artists rose to the challenge with an extraordinary assemblage of drawings and paintings. Produced behind the scenes as part of the normal currency of studio activity, many of them were never intended for public viewing. Together, they suggest something of the achievement represented by this historic film.

The Seven Dwarfs

If Snow White represented one kind of challenge for the animators, the other title characters, the Seven Dwarfs, represented a challenge of a different kind.

The idea of casting the dwarfs as seven different personality types, identified by their names, was not a revelation that occurred in the course of production; it was embedded in Walt Disney’s concept of the film from the very beginning. As we’ve seen, earlier stage and film adaptations of the story had sometimes included slight differentiation of some of the dwarfs. By contrast, the earliest surviving story outlines of the Disney version, from mid-1934, are based on the idea of differentiating all the dwarfs by strong personality types. This concept—sometimes criticized by folklore purists as if it were a flaw in the film—actually stemmed from the nature of character animation at the Disney studio during those peak years and was central to Walt’s reasons for producing Snow White in the first place.

The wonderful explosion of creativity that emerged from the Disney studio in 1930s has been rightly celebrated, but viewers, then and now, have often failed to understand the heart of Disney’s breakthrough: personality animation. …As characters, the Seven Dwarfs were tailor-made for this artistic environment. If ever there was a textbook exercise in personality animation, this was it: seven characters, all of similar height and appearance, who must be designed and animated so that they could instantly be distinguished from each other. And, since earlier versions of the story had rarely bothered to single out any of the individual dwarfs, the Disney artists were essentially starting from scratch. It was an inspiring challenge.

The Queen and the Witch

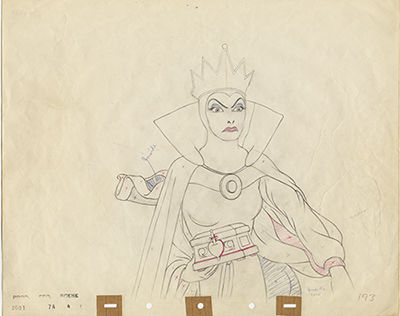

As the third major human character in the story, the Queen represented yet another daunting animation challenge. …Another early document, much quoted in latter-day accounts, described her as “a mixture of Lady Macbeth and the Big Bad Wolf—her beauty is sinister, mature, plenty of curves.”

The primary responsibility for animating the Queen was given to Art Babbitt—seemingly an odd assignment for an animator whose career highlights to date had been the development of Goofy and the mouse’s drunk scene in The Country Cousin. But Babbitt had a passion for the analysis of movement and the way it reflected character, high priorities at the Disney studio during the 1930s. Although he struggled with the technical demands of creating the Queen’s subtle, realistic movements, in the end Babbitt surmounted those difficulties and created the desired character—a Queen whose cold, hypnotic beauty was balanced by her forbidding and at times frightening nature.

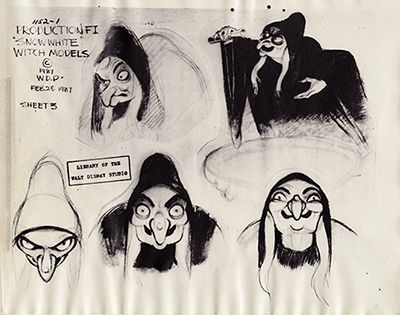

The Queen’s alter ego, the Witch, was an entirely different matter. Although she was to be every bit as frightening as the Queen’s beautiful self, it was recognized from the beginning that the rules of realistic human design and movement need not apply to the Witch. Because of her grotesque appearance, she was allowed a wide latitude of cartoon license.

Joe Grant had contributed the character design of the beautiful Queen and had even suggested her visual kinship with the Witch. In this model sheet, he explores the Witch in greater detail, capturing bother her maniacal glee in her transgressions and the very real menace that keeps her from being a comic figure.

The transformation into a witch clearly has a liberating effect on this character: in place of the Queen’s chilling, understated malevolence in the earlier scenes, [Norm] Ferguson animates her alter ego with a melodramatic flourish. As the Witch boldly utters her incantations over the poisoned apple, gleefully confides her plans to her pet raven, and stealthily makes her way through secret passages and misty marshes, her sheer pleasure in her misdeeds is unmistakable.

Premiere

The film was ready for showing in exactly one theater by December 1937. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs enjoyed a glittering star-studded world premiere at Hollywood’s Carthay Circle Theatre on the 21st of the month. A houseful of hardened movie-industry professional greeted it with laughter, tears, and overwhelming applause. Its success assured, the film settled into Carthay Circle for a run that would extend well into the following spring.

The long-awaited New York opening took place in January 1938 at Radio City Music Hall, perhaps the most prestigious motion-picture theater in the world. During 1938, the film continued to open across the country, then around the world, greeted everywhere by the same outpouring of delighted applause from critics and audiences. Snow White was not only a success, but an enormous, historic, record-shattering success; a milestone in film history. Theaters cancelled their bookings of other films to extend Snow White’s run. …Rival animation producers, who had once scoffed at the idea of a feature cartoon, now eyed the millions that Snow White was raking in at the box office and announced feature-length films of their own.

Music and Merchandise

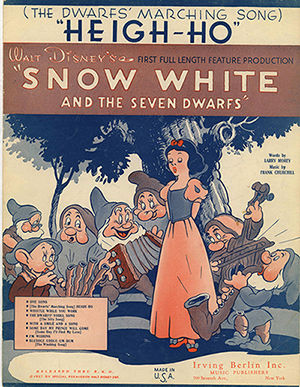

Along with the publicity, there was the marketing. An immense array of Snow White-related merchandise appeared in stores, aimed at both children and adults. For the children, there was a wide assortment of toys and dolls, and perhaps most fascinating today, storybooks. For adults, the success of Snow White in theaters was supplemented by its impact on the popular-music market. All the film’s songs were published in sheet-music form, most of them with verses not heard in the film. Several of them became hits in their own right, played on radio and records and performed by popular musicians. RCA Victor issued an elaborate album of the film’s soundtrack recordings, lavishly illustrated with Disney art.

More important to Walt than the attention were the opportunities that Snow White’s success brought him. Now he was free to pursue even more ambitious creative projects. For four years he had concentrated his attention on his lovingly handcrafted story of a fairy-tale princess; now, thanks to that dedication, his own dreams had come true.

See the entire rotation of the newly revealed Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs artifacts in gallery 3 at The Walt Disney Family Museum. To read more from The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: The Creation of a Classic, you can find it online and in our museum store on sale for a limited time.