Our Film of the Month for January is one of the finest adventure dramas of its era, Third Man on the Mountain. This film was only one of the manifestations of Walt Disney’s interest in outdoor recreation, sports, and adventure. Author and Disney historian Werner Weiss tells the story of a little-known project that would have been another component of Walt’s leisure legacy.

It was a Friday. It was about week before Christmas. And it was official: The U.S. Forest Service awarded the right to develop the Mineral King area of Sequoia National Forest to Walt Disney Productions. The year was 1965.

It was a Friday. It was about week before Christmas. And it was official: The U.S. Forest Service awarded the right to develop the Mineral King area of Sequoia National Forest to Walt Disney Productions. The year was 1965.

A wire service article quoted Walt Disney: “When I first saw Mineral King five years ago, I thought it was one of the most beautiful spots I had ever seen and we want to keep it that way.” To Walt Disney, that meant a self-contained “Alpine Village” designed to preserve the natural beauty of valley.

Other people wanted “to keep it that way” too. But to them it meant no development at all.

“U.S. Chooses Disney to Develop Sequoia Resort.” The news was on page 11 of the Los Angeles Times on December 18, 1965. According to the article, the U.S. Forest Service awarded a preliminary permit to Walt Disney Productions giving the company three years to complete a satisfactory plan. The next step would be a permanent 30-year permit.

Just a month earlier, Walt Disney announced that his company had purchased more than 27 thousand acres south of Orlando, Florida. According to initial reports, it would be a $70 million project, dubbed “Disneyland East” by the press, and include a “City of Yesterday” and a “City of Tomorrow.”

And now Walt Disney would also build a $35 million year-round resort in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. According to the article, “The Disney firm in its winning bid estimated that the new facility, 227 miles northeast of Los Angeles, would attract 2.5 million visitors annually—800,000 of them from out of state—by 1976, the first full year of operation.”

There just was the pesky matter of access into the Mineral King basin.

The 30-year permit was contingent on an all-weather, 25-mile highway. The route would go through Sequoia National Park. Mineral King was in Sequoia National Forest, under the jurisdiction of the U.S Department of Agriculture. But it was surrounded on three sides by Sequoia National Park, under the jurisdiction of the U.S Department of Interior.

The 30-year permit was contingent on an all-weather, 25-mile highway. The route would go through Sequoia National Park. Mineral King was in Sequoia National Forest, under the jurisdiction of the U.S Department of Agriculture. But it was surrounded on three sides by Sequoia National Park, under the jurisdiction of the U.S Department of Interior.

There was already road, but it was narrow, partially paved, treacherous, and only usable in months free from snowfall—not what you want for a ski resort.

In 1948, the Sierra Club had backed a plan for a ski resort at Mineral King, but the inadequate road killed the project. In 1958, recognizing that Mineral King had possibly the greatest potential for winter sports anywhere in the Sierra Nevada mountains, Tulare County asked the State of California to put in an all-weather road. There was finally progress in 1965 when the state legislature transferred the county road into the state highway system in anticipation of a new road.

With 2,500 permanent jobs at stake, the state would certainly go ahead with the highway, right?

At the end of this highway, visitors would find an Alpine resort that would redefine ski resorts, just as Disneyland had redefined amusement parks. The spring 1966 issue of Disney News, official publication of the Magic Kingdom Club, described what Walt Disney was going to build:

Walt’s plan for the picturesque area, located about equidistant from Los Angeles and San Francisco, provides for year-round recreational activities by people of all ages and athletic abilities.

Walt’s plan for the picturesque area, located about equidistant from Los Angeles and San Francisco, provides for year-round recreational activities by people of all ages and athletic abilities.

Fourteen ski lifts are anticipated, many serving guests throughout the year. Some of the lifts will be used in the warm months by sightseers, campers, hikers and wild-life students, who for the first time will be able to visit the 7,900-foot valley and its surrounding 12,400-foot mountains.

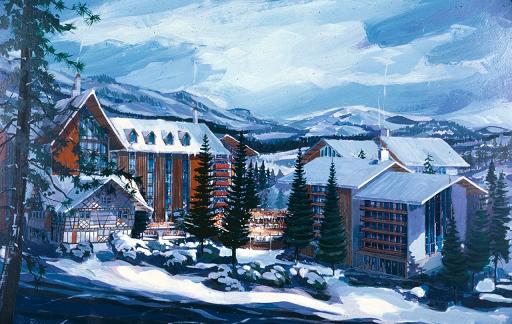

A completely self-contained village will accommodate visitors. It will have a chapel, ice-skating rink, convenience shops, restaurants, conference center, and low-cost lodging facilities. In addition to Mineral King Village and ski lifts, there will be a series of ten restaurants in the valley and atop surrounding peaks. There also will be two large hotels, a heliport and auxiliary facilities.

The company’s entire approach has been based on the absolute necessity to preserve the site’s natural beauty and alpine character.

To this end, automobiles will be excluded from the valley proper. Guests will park in a 2,500-vehicle parking area at the entrance and will be taken into the valley by a high-capacity public conveyance.

Further, the area’s natural character will be preserved by camouflaging ski lifts, situating the village so that it will not be seen from the valley entrance, and putting service areas in a 60,000 square foot underground facility beneath the village.

The magazine described how a snow survey group was already spending the winter at Mineral King to study snow conditions and collect data for construction.

A favorite piece of trivia among Disney theme park fans is how the Country Bear Jamboree was originally designed for Mineral King. However, that doesn’t mean that Mineral King would have included a theme park. The Audio-Animatronics® bears were planned as entertainers for one of the restaurants.

As 1966 progressed, plans for the highway moved ahead. In October, California Governor Edmund G. “Pat” Brown announced a $3 million Federal grant toward the $25 million price tag for the road. His next step would be to apply for $9 million Federal loan and to seek the balance from the California legislature.

With such strong support from the governor, it seemed certain that the road would be built. And given Walt Disney’s wonderful plans, the U.S. Forest Service was sure to grant the 30-year permit. Mineral King was on track.

On December 15, 1966, Walt Disney died. The Mineral King resort was destined to be one of many lasting reminders of his great vision and creativity when it opened—the final one. Or so it seemed at the time.

In the following years, the Imagineers at WED Enterprises refined their plans. Early drawings showing modern, 1960s-style structures gave way to renderings showing a more traditional Swiss Alpine village. In 1969 Disney News quoted Robert B. Hicks, Mineral King Project manager for the Disney organization:

“Buildings will be arranged so that each has its own individually-designed setting. Although structures will appear to be placed in random formation, their location will be dictated by natural land contours and appropriate architectural relationships, which will contribute to scenic harmony, general eye appeal, and a logical mix of lodging units, food service facilities, and other accommodations”

“Buildings will be arranged so that each has its own individually-designed setting. Although structures will appear to be placed in random formation, their location will be dictated by natural land contours and appropriate architectural relationships, which will contribute to scenic harmony, general eye appeal, and a logical mix of lodging units, food service facilities, and other accommodations”

The U.S. Forest Service approved Walt Disney Productions’ master plan for Mineral King on January 27, 1969. Skiers could expect the resort to open for the winter 1973 ski season, when the new road would also be ready.

During the years leading up to the approval, opposition to the Mineral King plans and the all-weather road had been growing. Opponents pointed out that Mineral King’s official name was the Sequoia National Game Refuge, and suggested that the development would desecrate the fragile valley. The Sierra Club—which had still approved a Mineral King recreational development as recently as 1965—attempted to use the courts to stop the project. Bumper stickers appeared with the message “Keep Mineral King Natural.”

There was still the issue that the road would have go through Sequoia National Park. As far back as March 1967, U.S. Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall expressed opposition to the road, suggesting that an electric railway or monorail would be better.

In May 1972, Walt Disney Productions announced a major revision to its Mineral King plans. The $35 million resort with as many as 22 ski lifts shrunk to a $15 million resort with 10 ski lifts. The scaled-down plans probably had more to do with financial considerations than with any attempt to reduce the project’s environmental footprint. Walt Disney Productions had opened Walt Disney World a half year before; the cost of that project, initially anticipated to be $70 million, had risen to $400 million.

The biggest change in the new plans was that access to the resort would primarily involve a 15-mile cog railway to be financed with a $20 million Tulare County bond and operated by Disney without a profit. The railway would be nonpolluting, follow the old road, and require a much narrower right-of-way than the proposed all-weather road.

On August 18, 1972, California Gov. Ronald Reagan signed legislation removing a segment of the all-weather road from the state’s highway system. The Los Angeles Times quoted the governor:

On August 18, 1972, California Gov. Ronald Reagan signed legislation removing a segment of the all-weather road from the state’s highway system. The Los Angeles Times quoted the governor:

“I want to stress as strongly as possible that I am firmly in support of the development of Mineral King as a recreation area,” said Reagan. “Southern California urgently needs additional year-round mountain recreation areas.

“Development of Mineral King will help serve that need. However, I am convinced that proper development will not be hampered by the lack of a high-speed road.

“Alternate access methods will suffice and, in the end, better serve the needs of both conservation and recreation.”

Having the governor as a supporter was not enough.

On October 23, 1973, the Los Angeles Times published an article titled “Planned Mineral King Resort Appears Doomed.” With the Sierra Club still using the legal system to oppose the project, Mineral King was expected to be tied up in the courts for years. The legality of the proposed cog railway was called into question. And a new law meant the project required an environmental impact statement.

All work stopped until the completion of an environmental assessment in 1976.

In 1977, the U.S. Forest Service attempted to revive the resort plan, but by then Walt Disney Productions had walked away from the Mineral King environmental fight in favor of an entirely different ski resort location on private land at Independence Lake, north of Lake Tahoe.

In 1978, Congress removed the 16,200 acres of Mineral King from the National Forest and annexed it to Sequoia National Park. The bill even had language prohibiting downhill ski facilities at Mineral King.

The Battle of Mineral King was over. Did the right side win?

It wasn’t a battle between good and evil or between public interest and selfishness. National Forests and National Parks perform a balancing act between protecting nature and allowing visitors to enjoy nature. Mountains and forests should be available not only to hardy backpackers, but to visitors of all ages and physical conditions.

The U.S. Forest Service and Walt Disney Productions saw Mineral King as an opportunity to provide a much-needed new facility for mountain recreation in California. The development would have been a model of how such a facility can exist in harmony with its surroundings. One only needed to look at Lake Tahoe and Mammoth Mountain—with their development sprawl, traffic, asphalt parking lots, garish signs, and lack of aesthetics—to see how better Mineral King would be. By concentrating a large number of visitors in a compact, well-designed village, vast areas of nature elsewhere could remain untouched.

Conservationists saw Mineral King as the wrong place for such a recreation facility. The valley was essentially in the center of the Sequoia National Park, even though it was not within the park’s boundaries at the time. The plans were too large, required a highway that would be detrimental to Sequoia National Park, and would change the magnificent valley from a largely unspoiled wilderness to a tourist attraction overrun with people. The valley served as a preserve for many native animal species. And it already provided recreation for a significant number of hikers.

The revised Disney plan with the cog railway, fewer ski runs, and a smaller footprint might have been a good compromise. But by then it was too late.

© Werner Weiss, All Rights Reserved. Republished with permission.

Werner Weiss is a Disney historian, writer, and consultant. He is the Curator of Yesterland.com, “a theme park on the Web,” consisting entirely of erudite writings on the subject of Disney attractions that no longer exist.

On Saturday January 21 at 3:00pm, Urban Planner and Community Engagement Specialist Sam Gennawey hosts past Disney CEO and Museum Founder Ron Miller and architect David Price to discuss Mineral King: Walt’s Lost Last Project, the innovative (and now-forgotten) year-round mountain resort that was one of Walt’s last major projects.

Images: 1) Walt and an artist's rendering of the Mineral King valley. © Disney. 2) Walt and Cardon Walker during the Press Conference at Mineral King, September 19, 1966. © Disney. 3 ) and 4) © Disney. 5) Walt, with Willy Schaeffler (L) and Governor Edmund G. Brown (R), at the Press Conference for Mineral King, September 19, 1966. © Disney