In the days long before the hype of today’s multi-million dollar, multi-media movie promotion campaigns, theater owners were essentially on their own to drum up local interest in the upcoming movie features they had booked. To inspire and assist theater owners, Hollywood Studios, including the Walt Disney Studios; would send press books loaded with suggestions and artwork for promoting the upcoming feature. Over the years, press books were supplemented with additional promotional elements that served to whet the appetite of generations of eager moviegoers.

On Saturday, June 23, in the Walt Disney Family Museum Theater, Robert Tieman, past manager of the Walt Disney Archives at the Walt Disney Studios; gave the audience a glimpse at the process and content used in promoting early Disney films. The event began with an introduction by Walt Disney Family Museum Marketing and Communications Director, Libby Garrison, which highlighted Robert’s 20 year career working alongside Disney Archive Director and Disney Legend Dave Smith. Smith had encouraged Robert Tieman to write a book about a Disney subject that interested him. After years of going through the archive collections, Robert published his first book, Disney Treasures, in 2003. Since then he has published Disney Keepsakes and The Mickey Mouse Treasures, each of which features two dimensional replica documents and ephemera from the Walt Disney Archives. During his research he came across so much publicity and promotional material that he found enough to develop this presentation. Promotional materials were developed for all Disney features, so, to provide focus and context for this event, Tieman selected three films to illustrate typical movie promotional campaigns: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio and Cinderella. What followed was a quaint look back at a time before television and some of the promotions used to draw youngsters into movie houses across America.

The first step in the process of promoting a Disney feature was to introduce the film’s characters to the public. In the case of fairy tales, the main characters of the story were already known. However, the Disney treatment of the main characters and the newly developed personalities, which help to tell the story, were not. In the fairy tale story of Snow White, for example, there are seven dwarfs, but they were unnamed. In the version created by Walt Disney, each dwarf had a name and a distinct personality that was unique to his film interpretation of the story. To build anticipation for an upcoming feature, the studio utilized various methods of introducing the characters and the story. One key promotional technique was to run a serialized color comic in the Sunday paper. In 1938, over the course of several weeks audiences were introduced to Snow White, Dopey and the other dwarfs; and the wicked Queen and her alter ego, the old peddler woman in a comic strip. Over the years, such comics ran for 24 to 30 weeks in advance of a feature release. The comics were utilized into the 1980s. Robert reported finding a TRON (1982) serialized comic strip in the archives.

In addition introducing characters via the comic strip, theater owners were directly assisted in promoting the feature and the characters through the use of press books. Press books contained camera ready artwork and suggestions for their use in a promotional campaign. For Pinocchio, Tieman showed templates for ads that could be placed in local newspapers. Each ad featured a single character such as Lampwick, Stromboli or the Blue Fairy and came with a catchy quote about the character that built interest in wanting to know more about them. The template also had room for the theater owner to place the theater’s name and location before submitting to a newspaper.

There were many other creative opportunities for a theater owner to generate interest in an upcoming Disney feature and the press books offered several unique ideas. For the theater lobby, a Snow White wishing well was suggested where young patrons could make a wish and toss a coin; with the proceeds used to benefit a local charity. Another interactive suggestion was to set up a “magic mirror” behind which an employee would be stationed to answer questions for the little guests. For Pinocchio, drawings were included to inspire turning the theater ticket booth into Geppetto’s toy shop, as well as, suggestions for conducting a Figaro the cat lookalike contest.

Character appearances have long been a favorite of young and old alike. They had their beginnings for Disney movie promotions back in the late 1930s when the Seven Dwarfs appeared at Radio City Music Hall. The character costumes of the time were not the refined, accurately scaled, character representations we see today at the Disney theme parks. Rather, they were approximations of what the dwarfs in Walt Disney’s Snow White looked like. They appeared crudely made to today’s eye, but this was likely of no consequence to a child excited to see a real movie hero in person. Sometimes local theater owners simply borrowed the character costumes from an ice show, as was later done on Opening Day at Disneyland. Since there were no Disneyland character costumes when the park opened, costumes were borrowed from the Ice Capades. So, when you see Mickey and Minnie in Disneyland’s Opening Day footage, you are looking at the Ice Capades costumes, loaned to Disneyland, that had previously been viewed by thousands of children at the ice show as it toured the country.

Other suggestions for the use of characters included a three foot tall Pinocchio marionette that could be flown into the local airport and be greeted by local dignitaries and later be interviewed for radio spots and photographed for local newspaper stories. A somewhat scary suggestion was to place a Pinocchio character inside of a large birdcage to be driven around town on the back of a flatbed truck with a speaker system to announce the coming of Disney’s newest feature. Perhaps the strangest use of a character appearance was in a photograph Robert shared in which an obviously grown man was dressed as Pinocchio, seated on a donkey, wearing a mask that was far too small. This had the effect of disrupting the standard, and highly successful Disney “toddlerlike”, character head to body ratio. There was a sign on the poor donkey stated that the donkey used to be a “bad boy” in reference to what happens at Pleasure Island in the movie. The effect of the out of proportion adult size Pinocchio riding a former naughty child was very strange to say the least. It is therefore not surprising that Disney later took control of character costumes and established standards to ensure that any Disney character would have consistent look anywhere in the world they might appear. But, in the first decades of Disney movie promotion character appearance was decided by local theater owners and the results were sometimes inconsistent.

In addition to supporting theater owners in promoting films, The Walt Disney Studio provided art for magazine covers, contests and product giveaways. Tieman showed several examples of magazine covers, such as Liberty, Hollywood and Movie Mirror that featured Snow White, the Seven Dwarfs and the Prince. The cover stories were designed to build anticipation for the upcoming release. Some tabloids even tried to drum up sales with a story entitled “The Life and Death of Dopey”. This was pure sensationalism meant to exploit the popularity of Dopey. It was loosely based on a comment made by Walt Disney when asked if Dopey would appear in any future films. Walt had said that he had no further plans to use Dopey in features and the tabloids took that and went on a field day claiming the impending death of Dopey. A more positive use of Dopey’s popularity was seen in sheet music and even a recording of a song entitled Doin’ The Dopey. The song led to a dance craze which was also called Doin’ The Dopey. It apparently had seven distinct dance steps which are now lost to history.

Full page advertisements for Disney animated features appeared in many popular magazines. The magazine artwork was often done as side work by Disney artists. Tieman showed two colorful full page ads for Cinderella that were done early in his career by Disney Legend John Hench. The artist might make an extra $25.00 for their advertisement art in addition to their regular salary.

Restaurants joined in the fun by offering character related incentives to draw families into their establishment. Tieman showed a Thrifty Restaurants 49 cent child’s menu that featured an image of a Disney character, in this case Gus-Gus from Cinderella, on a coupon good for a lollipop. Since there were several characters for each film, the tease “collect them all” no doubt ensured several return trips to the restaurant. For Pinocchio children could order a “Monstro” soda at the five and dime store soda fountain.

Retail stores created Disney film themed store window displays and products. One furniture store had a window display for a Stork Furniture line of infant furniture that had a Snow White theme. A piano store featured a white piano that boasted a “Snow White” finish. W.T. Grant stores ran newspaper ads announcing a “Cinderella” days sales promotion.

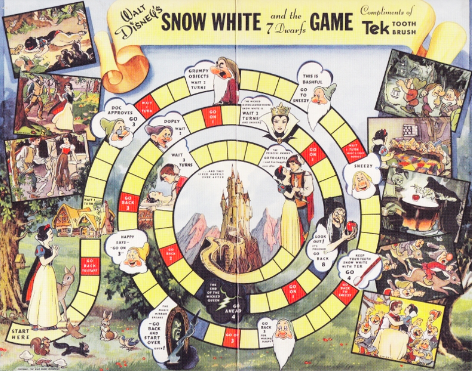

Product tie-ins and giveaways rounded out the promotional campaigns. Tieman shared several examples of novelties that were used to create interest in both the new Disney film release and a tie-in product that hoped to capitalize on the association with Disney characters. One free comic showed the seven dwarfs carrying home a Bendix washing machine. Tek toothbrushes offered a Snow White board game which featured the characters from the movie. In the 1950s Reynold’s Aluminum Foil gave a Snow White comic book with purchase. In one of the comic’s panels, a roll of Reynold’s aluminum foil was prominently placed on a table in the dwarfs cottage as Snow White was cooking in the kitchen. This, of course, implied that Snow White uses Reynold’s aluminum foil. Weatherbird shoes gave buyers a Pinocchio ring whose nose could be pulled out to represent his nose growing when telling a lie. For a Cinderella release, cottage cheese was sold in glasses with artwork from the movie. When the cottage cheese was used up, the glasses could be washed and re-used as juice glasses for the little ones. Things have changed in more recent times and Disney characters are no longer allowed to be shown in product advertising.

Product tie-ins and giveaways rounded out the promotional campaigns. Tieman shared several examples of novelties that were used to create interest in both the new Disney film release and a tie-in product that hoped to capitalize on the association with Disney characters. One free comic showed the seven dwarfs carrying home a Bendix washing machine. Tek toothbrushes offered a Snow White board game which featured the characters from the movie. In the 1950s Reynold’s Aluminum Foil gave a Snow White comic book with purchase. In one of the comic’s panels, a roll of Reynold’s aluminum foil was prominently placed on a table in the dwarfs cottage as Snow White was cooking in the kitchen. This, of course, implied that Snow White uses Reynold’s aluminum foil. Weatherbird shoes gave buyers a Pinocchio ring whose nose could be pulled out to represent his nose growing when telling a lie. For a Cinderella release, cottage cheese was sold in glasses with artwork from the movie. When the cottage cheese was used up, the glasses could be washed and re-used as juice glasses for the little ones. Things have changed in more recent times and Disney characters are no longer allowed to be shown in product advertising.

Robert Tieman, through the use of rare artifacts and images from the Walt Disney Archives, took the audience back to a simpler time to see how excitement was created for upcoming Disney animated features. It was a treat to see what our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents might have experienced when they were children eagerly anticipating the newest Disney film release.

Frank Teurlay is an inaugural member of The Walt Disney Family Museum volunteer team and can usually be found by the “Disneyland of Walt’s Imagination” model in Gallery 9. He is a regular program recap contributor to Storyboard, and has written for "Fantasyline Express".