In celebration of The Walt Disney Family Museum's 10th Anniversary, we're listing our 10 favorite highlights from our permanent collection.

1. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Honorary Academy Award®

Arguably, the highlight of our Awards Lobby is Walt’s collection of 26 Academy Awards®, the largest collections of Oscars® outside of Hollywood. Of all of Walt’s Oscars®, one outweighs the rest, literally. This special honorary Academy Award consists of one standard Oscar® statuette standing above seven other miniature ones representing each of the Dwarfs.

Shirley Temple was selected to present him with the award because she could stand in for Walt’s audience, the children of the world. While Walt would take issue with the insinuation that he only made films for children, he was more than happy (and not at all Grumpy) to accept the unique trophy, nonetheless.

Upon its release, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) had both the critical acclaim and box office success of a film worthy of an Oscars® conversation. To that point, it was the highest-grossing film of all-time. Unfortunately, the film’s status as the first feature-length animated film from a Hollywood studio separated it from every other potential Best Picture nominee, and it was thus kept out of the Best Picture discussion altogether.

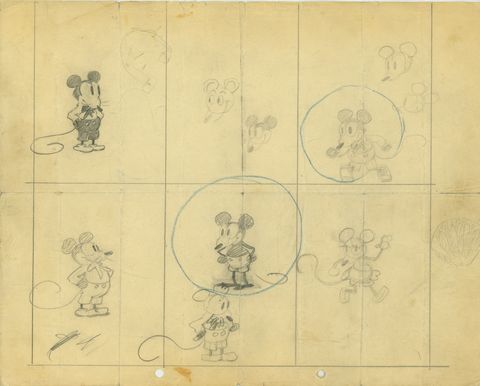

2. Earliest Known Drawings of Mickey Mouse

On aged, yellowed animation paper, you’ll see a few pencil sketches of a rodent-looking character, complete in suspenders and shoes. First named Mortimer, this mouse is now known the world over as Mickey Mouse. As a bonus, this sheet of paper also features the earliest known drawing of Mickey’s girlfriend, Minnie Mouse, showing that there was never a Mickey without a Minnie.

Recovered in a family vault decades after Walt’s passing, this authentic piece of Disney history can be found on display in Gallery 2B, where we cover Mickey’s early stardom. See the decision-making process laid out in rough animation sketches, as Walt, Ub Iwerks, and Les Clark ironed out designs that would become culturally iconic.

3. Synchronizing Sound Interactive Station

Steamboat Willie, Walt’s first cartoon with synchronized sound, became a global sensation thanks to the unique techniques used to add sounds directly to film. Steamboat Willierepresented a big break for a struggling studio after losing its prior star, and guaranteed financial solvency at a critical time right before the Great Depression hit.

At The Walt Disney Family Museum, our guests have the opportunity to synchronize sounds to Steamboat Williejust like Walt and his earliest sound effects technicians, before modern dubbing and mixing were possible. Bang a drum, tickle a xylophone, and even reproduce a cat’s yelp in this fun activity for the whole family.

4. Schultheis Notebook

Herman Schultheis was a camera technician at The Walt Disney Studios working on special effects for films such as Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), Dumbo (1941), and Bambi (1942). He kept an extensive scrapbook detailing all the tricks of the trade. Filled with photographs, artwork and detailed descriptions of how special effects were created at the Studios, these covert notebooks not only document movie-making wizardry, but also offer a glimpse inside the perplexing personal life of Herman Schultheis. Not too long after his sudden and abrupt termination at The Walt Disney Studios in 1940, Schultheis left the film business, and disappeared into the jungles of Guatemala in 1955. His notebook was all but forgotten until 1990, when historians discovered it hidden in his recently deceased widow’s estate.

Animation historian John Canemaker describes the Schultheis Notebook as “the Rosetta Stone of Disney animation.” The Schultheis Notebook is one of the many ways we ensure that every guest’s visit is unique. Though behind glass as an effort to conserve and protect the integrity of its pages, each month our Collections team flips the page of the notebook. This notebook has been entirely digitized so that visitors can explore, scan, and zoom through every single one of its pages which matches each page’s detailed processes with its finished product—clips from its corresponding feature film showing the special effect in action. Leaf through the pages of the Golden Age of Disney animation in Gallery 5.

5. Mary Blair Artwork

In 1941, Mary Blair joined the Disney expedition that toured Mexico and South America for three months and painted watercolors that inspired Walt to name her as not only his favorite artist, but an art supervisor on Saludos Amigos (1943) and The Three Caballeros (1945). Blair’s striking use of color and stylized graphics greatly influenced many Disney postwar productions, including: Song of the South (1946), Make Mine Music (1946), Melody Time (1948), So Dear to My Heart (1948), The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1953).

In 1964, Walt asked Blair to assist in the design of “it’s a small world”. Over the years, she brought her many artistic gifts to numerous exhibits, attractions, and murals at the theme parks in California and Florida, including the fanciful murals in the Grand Canyon Concourse at Disney’s Contemporary Resort at Walt Disney World.

Follow Mary Blair’s artistic transformation through her works on display in Galleries 6 and 7A, then see her theme park contributions in Gallery 9 at the Disney Museum in San Francisco.

6. Lillian Disney's Oscar® Charm Bracelet

In the early 1960s, Walt discovered he was able to purchase miniature Oscar® statuettes for his many wins, and decided to give them to Lillian to acknowledge the role she had played in his professional success. Twenty were assembled in total, each engraved underneath with the name of the film for which it was awarded. Made of 18K gold, Walt envisioned having a necklace made with these charms given to him by the Academy®; but Lilly said she’d prefer a bracelet.

In her later years, Lilly gave the bracelet to one of her granddaughters, who also treasured the stunning piece. Unfortunately, the bracelet was found missing after a time, apparently stolen by someone who had access to the family home. It wasn’t until a number of years later that the bracelet resurfaced in the Los Angeles area, and was reacquired into the family’s collection. Find yourself charmed in Gallery 7B, where Lilly’s bracelet is featured.

7. Griffith Park Bench

Walt Disney once said, “A man should never neglect his family for business.”

In addition to driving his daughters Diane and Sharon to school every day until they were of driving age, Walt would spend Sundays, or “Daddy’s Day,” with his girls, including a regular trip to Griffith Park to ride the carousel.

As Walt tells it, he would sit on a nearby bench, eating peanuts, thinking to himself that there should be an amusement enterprise that parents and children could enjoy together. Unsurprisingly, this daydream eventually coalesced into Disneyland Park, and opened a prolific chapter in both Walt’s life and the Company’s history.

Take in a breathtaking view of the Golden Gate Bridge while sitting on an authentic Griffith Park bench in Gallery 8.

8. Lilly Belle Train

“In one way or another, I have always loved trains.” —Walt Disney

There may not be a better icon for the intersection of Walt’s many interests and passions than the Lilly Belle. Named after Walt’s wife Lillian, the Lilly Belle is a one-eighth scale model of an actual steam engine train and ran on a half-mile track around the Disney family’s Holmby Hills home.

Putting together the Lilly Belle and the Carolwood Pacific Railroad was a task that was bigger than Walt, and brought together artists, machinists, and railroad enthusiasts that would constitute some of his earliest Imagineers. The Lilly Belle combines Walt’s lifelong interest in trains, his hobby of miniatures gained in adulthood, his desire to entertain people beyond the big screen, and his curiosity about modes of transportation that would inspire some of his final projects.

“All aboard!” to Gallery 9 where we have Walt’s original miniature train on display, complete with the caboose that was designed by Walt himself.

9. “The Disneyland of Walt’s Imagination”

Throughout our galleries are authentic pieces of Disney history that had been drawn, written, spoken, or supervised in some way by Walt Disney, so it may surprise new guests to the museum that one of the most memorable pieces on display was neither designed nor commissioned by Walt.

In the middle of Gallery 9 sits a 14-foot diameter model of Disneyland, but not a Disneyland that ever existed at any one time. Designed by Kerner Optical, formerly the practical-effects division of Industrial Light & Magic, this artistic rendering represents the Disneyland of Walt’s imagination, including attractions that Walt either saw put into the Park or had approved concepts of prior to his passing. This is how long-gone attractions such as Flying Saucers (1961–1966) can exist in the same physical space as Space Mountain (opened in 1977), or how the horse-drawn Conestoga Wagons and Stagecoaches (both 1955–1959) can be seen across the Rivers of America from the only new land that Walt helped open, New Orleans Square (dedicated in 1966).

10. Multiplane Camera

One highlight of our museum is so massive that we can’t contain it solely within our galleries! Its only rivaled in scale by its contributions to the art of animation as a whole.

One of three multiplane cameras left in the world is on display at The Walt Disney Family Museum and can be seen on the first floor in the Museum Store and the second floor in Gallery 5. The multiplane camera, which netted the Studios a technical Academy Award®, revolutionized animation by achieving the illusion of depth. In addition to being used immediately on the Silly Symphonies, it perhaps was pushed to its greatest limits in feature animated movies such as Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), and Bambi (1942).

Beyond the dazzling effects it was capable of reproducing, the multiplane camera represented an incredibly experimental and confident Disney Studios of the late 1930s and early 1940s that was unrivaled in the industry and created masterpieces that are just as fresh 80 years later.

Plan your visit to The Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco today!

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.

–Chris Mullen

Chris Mullen is the Senior Marketing and Communications Coordinator at The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image Sources (listed in order of appearance)

- Photo by Jim Smith; © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- Walt’s Honorary Academy Award for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, from the Academy Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences; photo by Jim Smith; © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- The earliest known drawing of Mickey Mouse, 1928; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Family at the synchronizing sound interactive station; © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- Schultheis Notebook; © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- Mary Blair, Alice in Wonderland (1951) concept art; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Lillian Disney’s Oscar® charm bracelet; photo by Jim Smith, © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- Two friends sitting on the Griffith Park bench (collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation); © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- The Lilly Belle; photo by Jim Smith; © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- Model of “The Disneyland of Walt’s Imagination” in Gallery 9; © The Walt Disney Family Museum

- Children looking up at the multiplane camera; © The Walt Disney Family Museum