Upon its release in late 1942, the Disney cartoon Der Fuehrer’s Face became a smash hit in the United States, winning the Academy Award® for Best Short Subject in 1943. But the home front was not its only theater of action. Der Fuehrer’s Face went overseas, and served the war effort in more ways than one. “It was the most popular propaganda film we had,” Walt Disney told journalist Pete Martin in the 1950s. “It was put in all languages… They had it in the underground. [They] were running it and were getting a good laugh out of it while they were under the heel of Hitler…”

To read more about the creation and American release of Der Fuehrer’s Face, click here.

A Little Souvenir from Great Britain

Great Britain Asks Germany to Play "Der Fuehrer’s Face" On The Radio

In early June 1943, a U.S. Army Air Forces bomber crew of a B-17 Flying Fortress decided to drop “a little souvenir” over Germany in the form of a 100-pound training bomb. Attached was a letter addressed to German radio’s “Miss Midge”—likely Nazi-employed propaganda broadcaster Mildred Gillars, also known as “Axis Sally”—deriding her to “please play on your program the song ‘Der Fuehrer’s Face.’” That same month in England—where the B-17 crew was stationed—it was reported that the Disney film was smashing box office records previously set by Three Little Pigs (1933).

“Wally” Saves Disney Films From Nazi Destruction

Raoul Wallace Feignoux was a native Parisian who in 1936 became Disney’s distribution representative in Europe. The Disneys knew him as “Wally.” When German forces occupied France in the summer of 1940, Feignoux took it upon himself to protect Disney’s film assets in the country, taking a great personal risk and coming into direct contact with Nazi operatives.

As historian Sébastien Roffat reports, Feignoux was essentially cut off from his American employers—the occupation making it “virtually impossible” to communicate. When word came of Disney’s contributions to the American war effort and making of “anti-Nazi films,” Feignoux struggled to convince the Germans not to destroy the Disney prints. At one point, he was taken to a “grim, darkened room” full of armed Nazis. “The atmosphere was most inhospitable,” Feignoux later explained to the Associated Press, “The [SS] are truly terrible men. They kill each other, their own people, as easily as the enemy.” Then Der Fuehrer’s Face appeared on a screen. “I heard no one laugh,” Feignoux would reportedly tell Walt after the war, “And Mr. Disney, I did not laugh either.”

The Disney representative quickly hid the remaining prints of Disney films, saving them from Nazi destruction. According to a later recollection by Feignoux’s sister Jacqueline Vieuille, “Wally had been brought up by our parents that you have to do your duty no matter the circumstances. He was proud to represent Disney and felt passion for his work.” Disney’s Paris offices on the Champs-Elysée were ironically, according to Vieuille, in the same building as the occupying Germans’ propaganda office.

Walt Disney corroborated parts of the Feignoux story in his interviews with Pete Martin. The journalist and Diane Disney Miller later adapted it for Miller’s series of articles and subsequent book, The Story of Walt Disney. Walt had explained that the Nazis “were always harassing” Feignoux. The first time they questioned him about Disney’s war-related work, the Parisian got out of it by explaining that “it’s just some little insignias and things,” and noted that even a nearby German patrol car had been unofficially painted with a figure of Mickey Mouse—such was Disney’s presence in popular culture. But when the Nazis presented him with Der Fuehrer’s Face, there was little Feignoux could do. “I’m here. Mr. Disney’s there,” he told them, according to Walt. “As soon as [Wally] got back [to his office] he knew that [the Nazis] would go through the steps back to headquarters,” Walt explained. “He got all of our films out of the vaults in the cans, put old films, old newsreel, old stuff, just put them in the cans.”

Wally Feignoux’s nephew Guy Feignoux later told Sébastien Roffat that his uncle “was a character with such an ability and such an ease to invent stories about him, that you could never know the true from the false.” Nevertheless, the reported drama of this wartime episode and its place in Walt’s own memory appropriately fits the energy and power of Der Fuehrer’s Face.

Starting Business with the Soviet Union

Disney WWII Propaganda Makes Its Way to Russia

Less than a week before Thanksgiving 1943, Hollywood columnist Thornton Delehanty reported that Disney was working to complete a Russian-language dubbing of Der Fuehrer's Face for distribution to the allied Soviet Union. It was reportedly suggested to Walt by interests Roy O. Disney later described as “Russian characters that were here during the war.” The elder Disney told historian Richard Hubler, “[We] gave this picture to Russia with a lot of prints. They used it and I understand it played over there widely. That was just a little war gesture on our part.”

Up until that time, Disney films had not officially played in Russia—according to Roy O. Disney, German bootlegs were typically brought into the country—but nonetheless, “We were very popular,” he explained. Later in 1953, Walt received a “beautiful trophy... a big cut-crystal cup with silver lacing on it” as the Soviet Cinema Festival Achievement award—it remains in The Walt Disney Family Museum collection, on view in the Awards Lobby.

For Der Fuehrer’s Face’s dubbing process, popular Russian-born actor Leonid Kinskey—who had just played Sascha the bartender in Casablanca (1942)—was recruited when Disney “launched a search for someone who,” according to the Los Angeles Times, “could speak Russian with a German accent.” Having worked in Germany, Kinskey was hired to collaborate on a translation with Jack Cutting, Disney’s innovative head of the Foreign Department. Cutting later told historians Christopher Finch and Linda Rosenkrantz that Donald Duck voice artist Clarence Nash learned the Russian lines phonetically.

“Since Russia was not at war with Japan and Italy at the time,” Cutting continued, “they insisted that we delete a sequence in Der Fuehrer’s Face that lampooned Mussolini and Hirohito.” (The Soviet Union declared war on Japan in August 1945.) According to later reports, a five-year agreement for two short subjects—the other remains unknown—along with the feature cartoon Bambi (1942) was reached in July 1943, and Cutting recalled Technicolor hand-delivering the film prints to a Russian ship off the California coast. Actor Leonid Kinskey told the Los Angeles Times that Walt made a “wonderful gesture” by selling the film negatives at cost to the Soviets and that “[Walt] is bringing laughter to a million kids suffering from this war.” (It remains unclear if the Bambi print was ever delivered, with evidence citing quality issues with the film’s dubbing and financial concerns over fair pricing.)

With thanks to Jim Hollifield, Didier Ghez, and Sébastien Roffat for their assistance.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image credits (in order of appearance):

-

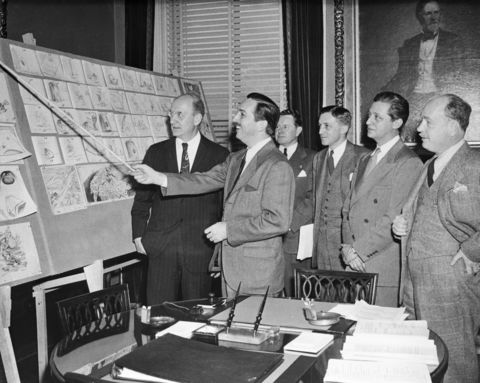

Secretary of Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Walt Disney, Assistant Secretary of Treasury John L. Sullivan, Assistant to the Secretary George Buffington, Disney artist Joe Grant, Disney writer Dick Huemer review a storyboard for The New Spirit, 1942; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library, Bettmann/CORBIS; © Disney

-

Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, #22, Vol. 2, No. 10, July 1942; collection of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney