90 years ago in 1932, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression. As millions of Americans struggled to find work, a new home, or simply a bite to eat, the movies became an important respite. Live-action hits of the year included the Busby Berkeley-choreographed musical The Kid from Spain starring Eddie Cantor and the high-swinging adventure Tarzan the Ape Man starring Johnny Weissmuller. Nearly five years earlier, the introduction of sound had altered the technical and creative paradigm of the movies.

Most of the visuals in popular cinema, however, remained in black-and-white. Color seemed to be one of the next innovations to challenge the craft of filmmaking. Dozens upon dozens of color processes had existed for years, but none exhibited a satisfyingly realistic or illustrative quality. This included animated cartoons, and as one of the medium’s dominant producers, Walt Disney was on the lookout for the right technique.

Walt Decides He Wants His Movies to Have Color

Years later, Lillian Disney would tell historian Richard Hubler that her husband wanted to try color because “it was new,” as she said. “He just wanted to do it. He was always interested in new things. I used to go along with him at night. We would go from theater to theater… He was just absorbing what everyone made—searching for new ideas and for new techniques to adapt.” Over the years, Walt would’ve seen a number of experiments in color projection, from hand-painted images to dyeing and stenciling, but none caught his attention like the emerging process of three-strip Technicolor®.

Walt recalled to journalist Pete Martin that “I had always been interested in color, but the color of the film at the time was not too good. It hadn’t met with too much success in the theaters because there was a certain blurry quality to it.” The moment came when Technicolor®—long a developer in the field—introduced an intricate process by which three separate rolls of film (for red, green, and blue) were combined into one saturated and vibrant image. Walt Disney Productions found their process and Technicolor found their means to promote it.

Flowers and Trees Gets Chosen to Be Colorized

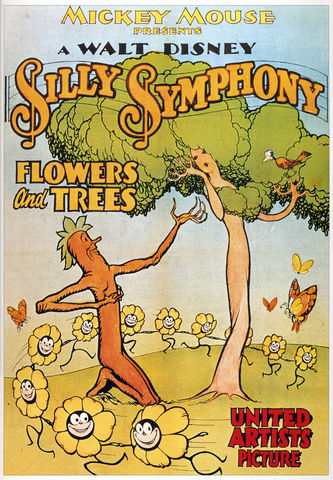

The financial resources to adapt three-strip Technicolor arrived courtesy of Disney’s new distribution partner, United Artists (UA). Although UA had more than doubled Disney’s budget, color was a risk that concerned them. Disney would not make its first color picture for the popular Mickey Mouse series, but rather the distinctive and often experimental series of stand-alone short subjects, the Silly Symphonies. Directed by Burt Gillett, the chosen short was a tale of plants and animals, Flowers and Trees (1932).

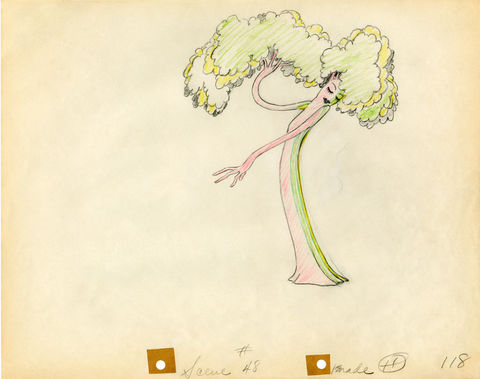

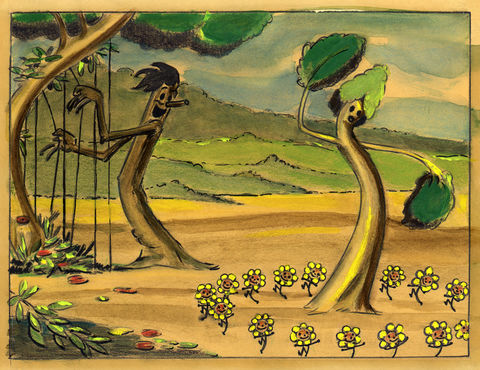

The cartoon presented the story of a romance between two anthropomorphized trees set against the drama of their woodland home coming under attack by a grotesque, decaying stump. The pastoral scene begins with the rising sun as awakening trees stretch and yawn and groups of daisies conduct morning exercises. The handsome gentleman tree swoons the elegant lady tree by crafting a harp out of vines as she sways to the music, all within the established tone and style of the earlier Silly Symphonies.

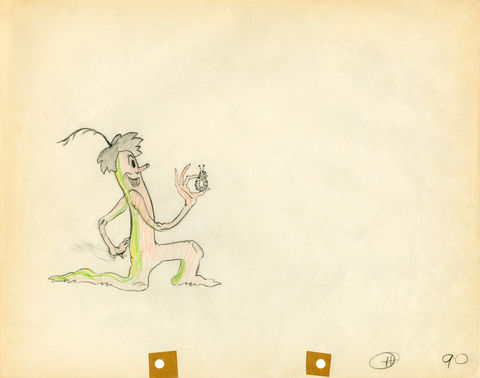

Conflict ensues when the jealous stump attempts to carry off the arboreal maiden. He attempts to fight his rival suitor, and when that fails, unleashes an army of spritely-embodied flames. Flowers ring the alarm bells as the flora and fauna struggle to escape the inferno. Resolution comes when a friendly flock of birds pierce open the clouds to shower rain onto the forest as the stump is consumed by his own creation. The short concludes with the male tree presenting his love with a ring fashioned from a smiling little caterpillar.

Adding Color Proves to Be Much More Difficult Than Anticipated

As historian Michael Barrier writes, “Flowers and Trees was the first film anyone made in three-strip Technicolor, although Disney had begun making it as a black-and-white cartoon; he ordered the change to color after the cartoon had already been shot.” Barrier quotes Disney’s then-cameraman Bill Cottrell that the studio Ink & Paint artists “took all the [black-and-white] cels and carefully washed all the reverse sides…then repainted them in color on the back.” Walt Disney himself would explain that “I just felt this color would do so much for the cartoon [medium] that it was worth doing the picture over.”

This of course marked a significant transition for the Ink & Paint Department, which under the direction of Hazel Sewell had to procure a new supply of color paints. As scholar Mindy Johnson writes, “Sewell’s department ran tests and developed color combinations to define each character and scene utilizing commercially manufactured paints.” It was not a smooth process, with weeks of film tests required to refine the color selection (to use the three-strip technique, the cartoon also had to be photographed at Technicolor’s own facility).

Nor was the process smooth on the administrative side, as United Artists continued to raise its eyebrow over the costs, and Roy O. Disney even expressed concern about the capability. For his part, Walt called the effort “the greatest campaign of persuasion in my life.” But when theater owner Sid Grauman viewed an incomplete work print, he was elated and requested to premiere the film at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. The cartoon itself had been completed only days earlier when it arrived in late July 1932.

Walt's First Color Cartoon Captivates Audiences Everywhere

90 years removed, it’s difficult to imagine the experience of entering a movie house with little or no frame of reference to vibrant Technicolor and watching something like Flowers and Trees for the first time. Grauman’s enthusiasm for the then-unfinished film provides some indication of just how visceral the audience’s reaction to the fantasy must have been.

The film continued to play across the nation over the coming months. “Disney has kept his famous Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony[sic] in front of all other cartoons,” wrote a Pennsylvania reporter that December, “and is the first to adopt color with their crazy antics.” That November, Flowers and Trees became the first cartoon to win an Academy Award® (Walt also won a special Oscar® for the creation of Mickey Mouse). “Walt Disney waited a long time before receiving the recognition now accorded,” wrote one Cincinnati paper, “for his creation of Mickey Mouse and the Silly Symphonies.”

One thing that has not changed in the movies is the ability of audience demand to shape the commercial market. Making use of its limited-time exclusive rights to three-strip Technicolor, Disney began producing all of its cartoon shorts in color within a few years (something United Artists had initially pushed back on, even after the success of Flowers and Trees). Other animation studios quickly adopted related methods. As Walt himself would say, “With Technicolor I figured that my competition would follow. And it did.”

Flowers and Trees’ Spectacle Revolutionizes the Industry

Walt Disney’s pioneering work in color was not, however, a mere gimmick to attract moviegoers to the latest technical fad. Color provided different opportunities for telling stories unique to the enhanced medium. The expressive range of the technique yielded new potential as Disney continued to experiment in creating narrative pathos onscreen.

The plight of the enchanted woods and its inhabitants came in the midst of a transition from the cyclical, rhythmic actions of the black-and-white cartoons that usually depicted plants and animals in repeated movements—driven, in part, by the earlier novelty of synchronizing movement and sound. The chorus line of daisies in Flowers and Trees is reminiscent of animation in the later Silly Symphony Springtime (1929). With the progression of the color technique, the actions of the scampering flames, for example, benefit from their red-orange hue, especially when pursued by the blue rain drops.

As Technicolor developer Herbert Kalmus observed in a 1938 essay, “If a script has been conceived, planned, and written for black-and-white, it should not be done at all in color. The story should be chosen and the scenario written with color in mind from the start, so that by its use effects are obtained, moods created, beauty and personalities emphasized, and the drama enhanced. Color should follow from sequence to sequence, supporting and giving impulse to the drama, becoming an integral part of it, and not something super-added.” With the enhancements of color as yet another tool at their disposal, Disney’s studio continued to develop emotionally-nuanced stories in the Silly Symphonies like The Flying Mouse (1934), Who Killed Cock Robin? (1935), and The Old Mill (1937).

Walt the Risk-Taker

Flowers and Trees was one of those characteristic gambles that, with the benefit of hindsight, appear at regular intervals across Walt Disney’s career, seemingly always at times when his business and creativity were in jeopardy. Risk necessitated risk. Comparing the making of Flowers and Trees to the later efforts on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Disneyland park, Lillian Disney explained to writer Bob Thomas that “when Walt went into color with Flowers and Trees, Roy was scared and so was I.” Walt understood that filmmaking and entertainment were inherently inconsistent and unpredictable enterprises that constantly demanded the artist to adapt and change.

But at the center of the tempestuous journey to keep the business alive, Walt did employ consistent approaches to how he told his stories, a mark of his artistic integrity and unwillingness to pander for the cheap dollar. Animator Ward Kimball—who would join the Disney studio in 1934—recalled to historian Jim Korkis that Flowers and Trees, like Snow White, exemplified “the real secret of Walt,” as he put it. “He didn’t do the stuff with his tongue in [his] cheek. When he did Flowers and Trees, which had a tragic ending, he was sincere. He believed in it. And when he did Snow White—here are these gross cartoon figures, nothing like you’d see in real life, all the animals acting like people—he was completely serious.”

Late in 2021, it was announced that Flowers and Trees would be among the new inductees into the National Film Registry of The Library of Congress, joining less than one thousand preserved titles, including a number of Disney animated features. Released subsequently to Flowers and Trees, they are all, of course, in color.

–Lucas Seastrom

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Image sources (listed in order of appearance):

-

Film poster, Flowers and Trees (1932); courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

-

Disney Studio Artist; Animation drawing from Flowers and Trees (1932); courtesy of the Walt Disney Animation Research Library; © Disney

-

Disney Studio Artist; Animation drawing from Flowers and Trees (1932); courtesy of the Walt Disney Animation Research Library; © Disney

-

Story sketch from Flowers and Trees (1932); courtesy of the Walt Disney Animation Research Library; © Disney

-

Paint jars, Gallery 3; The Walt Disney Family Museum

-

Walt with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) artwork, c. 1941; courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library and the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

Visit Us and Learn More About Disney’s Amazing History

Originally constructed in 1897 as an Army barracks, our iconic building transformed into The Walt Disney Family Museum more than a century later, and today houses some of the most interesting and fun museum exhibitions in the US. Explore the life story of the man behind the brand—Walt Disney. You’ll love the iconic Golden Gate Bridge views and our interactive exhibitions here in San Francisco. You can learn more about visiting us here.