In celebration of The Walt Disney Family Museum's 10th Anniversary, we'd like to look back and share some of our stories from the very beginning. This article was originally written and posted for our third member magazine in 2010 by Academy Award®-nominated animator, director, and producer Don Hahn.

Although Snow White (1937), Pinocchio (1940), and Bambi (1940) set the stage for Walt Disney’s landmark success in the 1930s, no one could have predicted that World War II, labor disputes, and an empty bank account would bring the prolific studio to the brink of closure. But, no one doubted Walt’s determination and his ability to find three more imaginative stories that would bring the studio back to life: Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1953).

As the final film in the trilogy, Peter Pan was a tale of lost boys, pirates, and mermaids based on a story by Scottish playwright J.M. Barrie. Walt wanted the rights as early as 1935, but it wasn’t until five years later, after Barrie’s death, that the rights materialized, and another thirteen years from then that the film hit theaters.

Produced with a freshness and mastery that became the hallmark of the Disney Studios in the 50s and 60s, the film is the last to be animated by all of Disney’s famed animators, the Nine Old Men. At the helm were three veteran Disney directors: Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, and Ham Luske.

Long-time collaborator Oliver Wallace—who had scored Dumbo (1941), Cinderella, and Alice in Wonderland—was brought in to score the film, and Walt hired the best songwriters of the pre-Sherman Brothers era, Sammy Fain and Sammy Cahn. Fain had written the songs for Alice just two years earlier. And to sing, Walt tapped The Mellow Men, a hugely popular quartet of singers founded by Thurl Ravenscroft, who voiced dozens of characters for Disney films and a bucketful of characters in the parks, not to mention Kellogg’s mascot, Tony the Tiger.

It was the perfect storm of people at the height of their creative powers, but the team needed a creative spark to launch the look of the film. Enter Mary Blair. Blair came to the Studios in 1940, working briefly on Dumbo. A few years later, she traveled to South America with Walt and Lillian Disney and a troupe of artists that Walt dubbed “El Grupo.” Her work was profoundly affected by that trip.

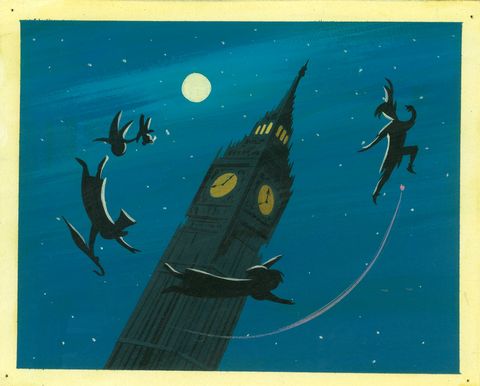

When Walt launched visual development on Cinderella, Alice, and Peter Pan, Mary was drafted to be the lead conceptual artist for the series. It was no secret that Walt loved her sense of design and once jokingly called her “colorblind” for her fearless approach to color. Her work on Peter Pan was free, child-like, and beautifully stylized. Pan would be her last film before a protracted leave from the Studios to do advertising and children’s books. Years later, she would return for a second round of brilliant work on “it’s a small world” for the 1964/65 New York World’s Fair, as well as dynamic murals for Tomorrowland at Disneyland and the Disney’s Contemporary Hotel at Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Florida.

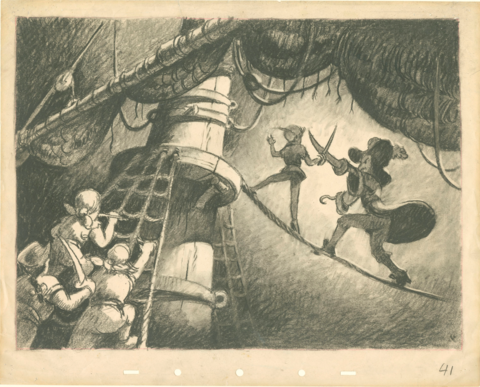

During production, the Studios summoned every trick in the book to execute Peter Pan as quickly and inexpensively as they could, while maintaining the utmost quality. Bill Peet, Bill Cottrell, and Winston Hibler, all Studios heavyweights, had a great story to work with. The real task was in the execution of the animation. Nearly all the characters were human, yet they all had a caricatured style. So how do you quickly study and draw humans who are at times realistic like Wendy and John Darling, and at others wildly cartoony like Smee and the lost boys? The answer was a technique that had been invented and patented in 1919 by one of Disney’s competitors, Max Fleisher, the producer of the Out of the Inkwell series. It was called the rotoscope.

When I came back to work at the Disney Studios in Burbank in the mid 1970s, the rotoscope machine was still there, installed in a dark room in the 2C animation wing of the studio, just a few steps away from Woolie Reitherman’s office. Here’s how it worked: Live characters were dressed in costumes and filmed on 35mm film; then the film was developed and brought to the “roto room” where it was projected one frame at a time onto a drawing board. The animators could then use the film as reference for movement. It was a technique they used on Snow White when they filmed dancer Marge Champion and rotoscoped them for scenes of Snow White. The animators still had to draw and animate the performance, but the roto technique gave them a complete frame-by-frame study guide for locomotion.

Walt employed the same actors to do the rotoscope filming that he had hired to do the voices—Bobby Driscoll and Kathryn Beaumont as Peter and Wendy, and the amazing character actor Hans Conreid in the dual roles of Mr. Darling and Captain Hook. By using the same actors, the live-action performances blended perfectly with the character voices, and it all represented a big plus for the film in quality and efficiency.

There was even a persistent rumor that Marilyn Monroe provided the reference model for Tinker Bell. Not true, the honor went to Margaret Kerry. Kerry, an aspiring actress, had just won a contest for the “World’s Most Beautiful Legs” and answered an audition call to meet with animator Marc Davis. The job required her to pantomime all of Tinker Bell’s performance. Davis gave her the role, and then spent six months filming with her on a soundstage where the simplest of wire-frame props would suggest giant keyholes, scissors, and a jewelry box.

Today, we marvel at the idea of “performance-capture” in films like Avatar (2009) and Robert Zemeckis’s A Christmas Carol (2009). But it all started 90 years ago with a technique invented by Fleisher and perfected by the Disney Studios, a technique that is still used today.

Peter Pan was a triumph that, along with Cinderella, drove millions to the box office and gave the Disney Studios a new lease on life. Walt Disney—the visionary, the businessman, and the technical guru—had a vibrant animation studio once again. Today’s generation of animators continues to aspire to the high level of quality established by Walt. He knew, as we know today, that great animation, color design from artists like Mary Blair, acting, and a story like Peter Pan, were the heart and soul of his studio.

–Don Hahn

Don Hahn serves on The Walt Disney Family Museum's Advisory Committee and is an Academy Award®-nominated animator, director, and producer.

Image Sources (in order of appearance):

- Kathryn Beaumont (Wendy) and Roland Dupre (Peter) acting out a flight scene as part of the live-acting filming of Peter Pan (1953) for animator use; Courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney

- Peter Pan (1953) story sketch; Courtesy of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Blair, Mary; Peter Pan (1953) concept art; Courtesy of the Walt Disney Family Foundation; © Disney

- Bobby Driscoll (voice of Peter Pan) in costume with Walt Disney on a sound stage; Courtesy of the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library; © Disney