Disney historian, Jeff Kurtti, takes time to reflect on the passing of Leslie Neilsen and reminds us that in the beginning of his career, Nielsen had been part of the Walt Disney family of television stars.

When James MacArthur passed away in October, little was said of his early film career and four feature films with Walt Disney.

With the death of Leslie Nielsen on Sunday, the brief but memorable work that the actor did with Walt Disney was likewise briefly mentioned, or ignored altogether.

Nielsen was born in 1926 in Saskatchewan, Canada. Following his graduation from high school in Edmonton, Nielsen enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and was trained as a gunner. He received a scholarship for the Neighborhood Playhouse, and moved to New York City. Afterward, he attended the Actors Studio before making his first television appearance on a 1948 episode of Studio One, alongside Charlton Heston. He appeared in almost 50 live TV programs in 1950 alone, but this early work was uneventful.

In 1956, he made his feature film debut in the Michael Curtiz-directed musical The Vagabond King. Although the film flopped, producerNicholas Nayfack offered him an audition for Forbidden Planet, which led to a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where he appeared in such films such as Ransom! (1956), The Opposite Sex (1956), andHot Summer Night (1957). In the same year, Nielsen was the romantic lead opposite Debbie Reynolds on a loan-out to Universal in the surprise smash, Tammy and the Bachelor.

Nielsen was unhappy with his treatment by MGM, though, and was soon casting about for other roles across all media. One of the producers who Neilsen was fortunate to interest was Walt Disney.

Since the overnight sensation of the Davy Crockett series on theDisneyland TV program in 1954 and 1955, ABC had pressured Walt and producer Bill Walsh to deliver “another Davy Crockett.”

The Saga of Andy Burnett was the first new “Frontierland” hero, a fictional character based on the book series by Stewart Edward White. The series was (in too many ways) reminiscent of Davy Crockett, without delivering the same kind of positive audience reaction, and only lasted six episodes.

Never one to follow trends, Walt was uncomfortable with and resistant to the continued pressure from the network, not only because of the soft performance of “Andy Burnett,” but because the Western genre itself had never been the reason for his interest in the Davy Crockett series.

In addition, seven of the 20 most popular TV programs of the 1957-58 season were what the movie trade papers called “oaters” (from the fondness of horses for oats). Walt knew when to take advantage of a trend—and also when a project would be following the very shaky path of a simple fad.

But finally, even though the creative directive from the network rubbed Walt the wrong way, Donn Tatum, then production business manager (and later the first non-Disney family member to be president) of Walt Disney Productions recalled how Walt finally called a meeting with the ABC executives. After the meeting gathered, Walt strode in the room dressed from head to toe in Western gear, threw his pistols on the conference table, and said, “Okay, you want Westerns, you’re gonna have Westerns!”

Elfego Baca had been a real figure in the waning days of the old West, a lawman, lawyer, and politician in Southwestern New Mexico. Although little-known at the time of his death in 1945, Disney’s 10-part mini-series, aired between late 1958 and early 1960, starred Robert Loggia and was well-received—and created what historian Ferenc Morton Szasz called “America’s first Hispanic popular culture hero.”

Elfego Baca had been a real figure in the waning days of the old West, a lawman, lawyer, and politician in Southwestern New Mexico. Although little-known at the time of his death in 1945, Disney’s 10-part mini-series, aired between late 1958 and early 1960, starred Robert Loggia and was well-received—and created what historian Ferenc Morton Szasz called “America’s first Hispanic popular culture hero.”

From 1958 to 1961, 17 episodes of Texas John Slaughter aired on the Disney TV program (“Texas John Slaughter made ‘em do what they oughta, and if they didn’t, they died,” went the theme song). Strapping and handsome Tom Tryon played another actual figure from American history. Slaughter was a Civil War veteran, trail-driver, cattleman, Texas Ranger, Cochise County Sheriff, gambler, and finally an Arizona State Representative. This series was also a moderate success.

A four-episode 1960-61 Disney series based on the life of pre-Revolutionary pioneer Daniel Boone (starring Dewey Martin) was much less successful—and in the shadow of the huge sensation of Fess Parker’s later long-running TV series has been almost completely forgotten.

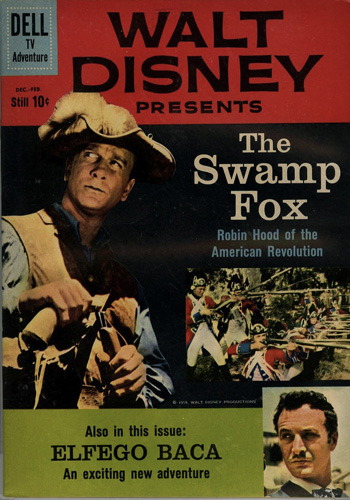

Francis Marion, better known as the Swamp Fox, is said to have helped to turn the tide of the American Revolutionary War. This more unconventional American hero was probably more appealing to Walt than what had become the typical—and ubiquitous—TV “cowboy” of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Marion’s unusual fighting tactics included concealment in the Carolina swamps, and attacking the British by stealth as they marched in rigid formation. Because Marion and his men knew the topography so well, his opponents could not track him, nor could they anticipate his attacks. His opponents accused him of forsaking the gentlemanly methods of war; he was hailed as “the Robin Hood of the American Revolution.”

In many ways, the stories of the Swamp Fox had more of the feel of espionage and spy tales than of a typical Western—a difference that Walt might have found an interesting variation on what was becoming a monotonous theme in television: a series of “road company Davy Crocketts.”

The lead actor needed an unusual combination of masculine appeal, agile physicality, cleverness and intelligence, and romantic attraction; since all of these traits were part of the Swamp Fox tales. Leslie Neilsen had exhibited all of these qualities in his film work, and seemed a comfortable fit as a big hero for the small screen.

In addition to the casting of Nielsen as Frances Marion, many familiar Disney stalwarts were also featured in the series, including J. Pat O’Malley (Alice in Wonderland, Spin and Marty), Hal Stalmaster (Johnny Tremain), and Tim Considine (Spin and Marty), Eleanor Audley (Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty).

Although his starring role in The Swamp Fox had become a footnote for Disney fans by the time Leslie Neilsen became renowned for his work in film comedies such as Airplane! and The Naked Gun series of features; in a 1988 interview, Neilsen reflected on his work with Disney, and his admiration for Walt’s standards, saying, “That was a great experience, because the Disney people didn’t do their shows like everyone else, knocking out an episode a week. We only had to do an episode a month, and the budgets were extremely high for TV at that time. So we had location shooting, rather than cheap studio backdrops, and very authentic costumes.”

Although his starring role in The Swamp Fox had become a footnote for Disney fans by the time Leslie Neilsen became renowned for his work in film comedies such as Airplane! and The Naked Gun series of features; in a 1988 interview, Neilsen reflected on his work with Disney, and his admiration for Walt’s standards, saying, “That was a great experience, because the Disney people didn’t do their shows like everyone else, knocking out an episode a week. We only had to do an episode a month, and the budgets were extremely high for TV at that time. So we had location shooting, rather than cheap studio backdrops, and very authentic costumes.”

Unfortunately, neither the critics nor the public responded to the eight episodes of The Swamp Fox aired between October 1959 and January 1961 in the way that they did to Davy Crockett.

In fact, one could make the case that the “The Davy Crockett Craze” (like the blockbuster success of The Lion King decades later) was a huge cultural anomaly that was simply impossible to recreate as what is now clinically referred to as a “franchise” (even though people in Hollywood who should have known better spent years of their careers trying to do so).

You cannot catch lightning in a bottle, and no one seemed to know this more instinctively than Walt. He had little desire to simply repeat his successes. Using them as springboards to further innovation was of far more interest to Walt Disney.

All images courtesy of the Walt Disney Company.