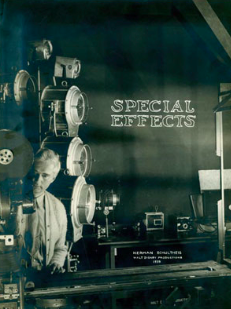

In August, the Look Closer series focused on the unique notebook in Gallery 5, found amidst images, artwork, and footage from the 1940 classic Fantasia. The notebook was created by studio employee Herman Schultheis, who worked for the studio’s Process Lab Department from 1938 to 1940.

During his tenure at the studio, Schultheis worked on and witnessed the production of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi. He kept a detailed journal about the studio’s production on these films, focusing primarily on how the special effects were achieved. The notebook contains photographs, diagrams, and written descriptions demonstrating the experimental and collaborative nature of the studio during this period, when it arguably produced some its most ground-breaking work.

During his tenure at the studio, Schultheis worked on and witnessed the production of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi. He kept a detailed journal about the studio’s production on these films, focusing primarily on how the special effects were achieved. The notebook contains photographs, diagrams, and written descriptions demonstrating the experimental and collaborative nature of the studio during this period, when it arguably produced some its most ground-breaking work.

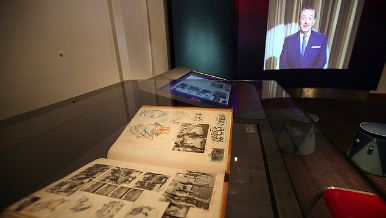

The notebook can be seen on display in the gallery that is devoted to the art and production of the animated features released in the early 1940s. The notebook is accompanied by a unique interactive touch-screen display on which visitors may scroll through and zoom in on each of its eighty oversized pages. The interactive display includes video clips that correspond with the moments referenced by Schultheis in the journal.

The notebook demonstrates the step by step processes over years of hard work and experimentation that resulted in the visual brilliance of the animated films. The astounding growth and creative explosion at the Disney studio during this period is only too evident in the studio’s first few features.

The groundwork had been laid during production of the Silly Symphonies, a series of short cartoons produced between the years of 1929 and 1939. The series challenged animators to expand the boundaries of the art form and leap ahead into uncharted territory. The experimentation and development resulted in several key innovations, including color, depth, personality animation, story development, and the use of music.

The production of this series of films prepared Disney artists for the challenges of producing feature-length animated films, as well as bolstered the Disney name as the leader in quality animated entertainment.

The studio spared no expense for the production of feature animated films. Walt’s mentality was to “go for broke,” meaning allocating as much of the studio’s resources as possible to ensure the highest quality product. The lavish special effects used on the films demanded increasingly more time and money, as well as elevated the visual quality of the films. Hundreds of animators created each scene meticulously, with very detailed planning. Several artists collaborated on each animated moment – the instant when Pinocchio tells a lie and his nose extends was shared by several specialized animators.

Fantasia was easily one of the studio’s most ambitious projects. The concept originated from the idea for a Mickey Mouse short entitled “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” Walt had become concerned about the future of the character of Mickey Mouse and decided to create a two-reel pantomimed version of the old folk tale “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” to the music by Paul Dukas.

After a chance meeting with renowned conductor Leopold Stokowski, the concept for the project began to grow. Stokowski suggested that other famous compositions could also be interpreted in animated stories, and the concept for a full-length feature emerged, originally entitled simply Concert Feature.

After a chance meeting with renowned conductor Leopold Stokowski, the concept for the project began to grow. Stokowski suggested that other famous compositions could also be interpreted in animated stories, and the concept for a full-length feature emerged, originally entitled simply Concert Feature.

For another animated segment, Stokowski suggested the use of J.S. Bach’s tour de force Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. After discovering that Bach had often improvised his compositions when struck by inspiration, Walt decided that the corresponding animation should be similarly free and interpretational in feel. This piece in particular demonstrates music visualization in its most abstract sense – the artists used the sensations experienced by listening to the music to inspire color, shape, speed, and texture. The music was used foremost as a tool for creating animation.

A number of innovative effects were utilized for the sequence set to Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite. For the Waltz of the Flowers segment, actual lights were placed on the movement pathways of the fairies, as had been done for the fireflies in The Old Mill and candles in Snow White. Frosted cels were used to create various textures, and light reflected off of chips of metal from different angles created the shimmering effect of dew drops on flowers. Spinning snowflakes were filmed in live-action on rotating gears for the whimsical finale of the segment.

The studio also developed an entirely new sound system created specifically to do justice to the tremendous pieces of classical music. Known as Fantasound, the multichannel sound system aimed at reproducing the experience of hearing live classical music in a concert hall. The effect was accomplished by recording music using several microphones in various locations around the source of the sound, and then placing an equal number of loudspeakers surrounding the theater space in the same arrangement. The system resulted in a stereophonic effect, and was the forerunner to today’s surround sound techniques.

Even after seventy years, Fantasia feels fresh and imaginative. It was the vision of Walt, the artists, and people like Herman Schultheis that expanded the vocabulary and the creative potential for the art of animation.

Alyssa Carnahan

Museum Educator

[Images: Top--Courtesy Walt Disney Family Foundation. Bottom--Courtesy Second Story.]