Make Believe: The World of Glen Keane is open through September 3, 2018 in the Lower Lobby and Theater Gallery at The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Animation has always been a family affair for Glen Keane. The son of cartoonist Bil Keane, creator of The Family Circus, Glen began drawing at an early age. As a child, he drew to make the paper go away and, in the process, discovered the dimensionality of imagined worlds. Keane harnesses the freedom and fearlessness of thinking like a child to fully immerse himself in and have a conversation with what he is drawing; this is the key to his creativity and essential to the art of playing make believe.

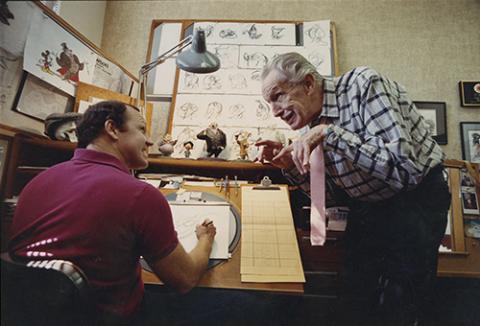

Glen Keane left the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in 1974 to join The Walt Disney Studios where he learned how to approach animation from legendary Disney artists Eric Larson, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston—three of Walt Disney’s “Nine Old Men.” Eric Larson, a grandfatherly figure, taught Keane the importance of sincerity to Disney animation while working on the character of Bernard for The Rescuers(1977). This film also allowed Keane to work with Johnston, a man whose love of trains—common among many animators at the Studios during Walt’s tenure—reinforced the importance of childlike wonder to the art of animation. Each character brought new challenges and deeper insights for the young animator, but the caliber of Keane’s work elicited praise from his mentors.

“I have a strange belief that characters exist before I design them. Though I had drawn hundreds of variations of the Beast, I knew none of them were truly him until one day my assistant asked me to show him what the Beast would look like. I started to draw Beast based on a buffalo head I had hanging on my office wall, adding a wild boar muzzle…the mane of a lion…cow ears…and, finally, eyes of the Prince. Suddenly, Beast appeared, and I said, ‘There he is, that’s him!’ I recognized him as if I’d always known him.”

These characters may exist before Glen Keane designs them, but his total commitment to discovery is what brings them to life. Understanding characters from the inside out also enables Keane to recognize applicable traits in the people around him—from actors in favorite films to his extended family and even his boss. Keane stated, “As Tarzan looked into Jane’s eyes, I imagined him seeing his reflection in the face of another human for the first time. I wondered when I had experienced such a thing, and I remembered holding my daughter Claire—looking into her face and seeing myself. I told Claire years later: ‘When you see Tarzan looking into Jane’s eyes, that’s really me looking at you for the first time.’”

“My family and I had moved to Paris where I was searching for a way to animate Tarzan that gave justice to Edgar Rice Burroughs’ descriptions of his fearless jungle acrobatics. My son Max, who was 15 at the time, would come home with bloody elbows and knees from trying stunts on his skateboard. As he and I would watch extreme sports videos together, I realized that Tarzan must be like them: addicted to the adrenaline rush of pushing oneself to the limits. Instead of a rather passive Tarzan that hangs onto a swinging vine, this Tarzan would be a tree surfer, launching himself fearlessly from limb to limb.”

For the film The Great Mouse Detective (1986), Keane remembers, “Ratigan was a conflicted character; very self-conscious about being a rat so he moves with an air of grace and sophistication, but with the comedic timing of Vincent Price in Champagne for Caesar (1950). My other source was our boss, Ron Miller—an ex-pro football player for the Los Angeles Rams and President of The Walt Disney Company. One story meeting when Ron entered the room, his power and presence inspired me to design Ratigan.”

Keane’s commitment to character and craft is complemented by his willingness to embrace new technology. Although computer-generated imagery (CGI) is increasingly universal, he started experimenting with the medium early in its adoption at Disney; however, sometimes the vision is ahead of the technology. Responding to the challenge of combining hand-drawn techniques with computer animation, Keane asked himself: “what is drawing?” Drawing is really about the illusion of sculpting in space, drawing a line that creates the invisible form within it and constructs the space around it. This concept of “sculptural drawing” is what helped him to build a bridge between traditional animation and computer-generated imagery (CGI) in Tarzan (1999), Treasure Planet (2002), and Tangled (2010).

His wife, children, extended family, and faith have been constant sources of inspiration throughout his career at Disney and beyond, and will be a recurring presence throughout this exhibition. Make Believe: The World of Glen Keane is open through September 3, 2018 in the Lower Lobby and Theater Gallery at The Walt Disney Family Museum.