Being an epic of animated cinema, Pinocchio (1940) is ripe with moments of artistic beauty and raucously fun entertainment. Walt Disney was as confident as ever coming off the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). He was anxious to put even more effort and dedication into the second feature. The result was a dazzlingly classic film. And Sequence 8.3 of the feature, the scene in the fabled pool hall, is a stand out for its combined mastery of the animated art form, thanks in particular to three of Walt’s best animators.

Directed by Ham Luske (a former animator), the sequence was one of the funniest moments of character interaction in the picture. When deciding on a vice for the innocent Pinocchio to indulge in with his newfound friend, Lampwick, Walt and his story team settled on what J.B. Kaufman describes as “that classic environ of misspent youth: the pool hall.” Billiard parlors had long been a symbol of the degenerate in American culture. In his Broadway musical of 1957, “The Music Man,” composer Meredith Willson chose such a locale as subject matter for the famous song, “Ya Got Trouble,” where the travelling salesman manipulatively warns the strait-laced Iowan townsfolk of the dangers to come if their youth became enveloped in pool hall life, comically singing, “That’s trouble with a capital ‘T’ and that rhymes with ‘P’ and that stands for ‘pool’!”

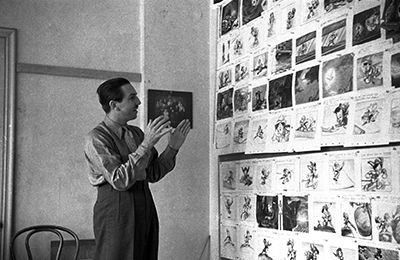

Walt was a master at casting animators to characters and scenes. He understood each artist’s particular talents and sensibilities and how such could best translate into a story. The sequence in Pinocchio was animated by a number of the hardest working artists at the Hyperion studio, including John Elliotte, Berny Wolf, and Milt Neil. Even more effects animators took on the strenuous tasks of animating puffs of dust and the crash of billiard balls. However, it’s to three character animators- Fred Moore, Ward Kimball, and Milt Kahl- that we can best look at this scene’s success. In a way, Walt’s leadership would orchestrate a veritable duel of the masters.

The scene opens with an exterior of the Pleasure Island pool hall, which is appropriately designed as one giant black “8 ball” and towering cue stick with western style swinging doors at the front (the structure might be visual mockery of the “Trylon” and “Perisphere” at the 1939 New York World’s Fair). Things have quieted down somewhat in the wild environment of misbehavior, and Pinocchio and Lampwick have settled in for some cigars and billiards. All of course was intended by Walt as a humorous cautionary tale to audiences. Later, Jiminy Cricket storms into the room, finally having caught up with the title character and furiously condemns Pinocchio’s behavior, much to the amusement of Lampwick. “What could represent ill repute more than smoking a cigar in a pool hall,” historian Leonard Maltin would humorously describe in Pinocchio’s audio commentary on the Disney DVD.

Lampwick, with his calm and confident demeanor, was animated by Fred Moore. Almost a caricature of the animator’s own appearance, the cocky friend of Pinocchio is exaggerated in his poses, moving from one to the next as the character intends to rather elegantly shoot pool. There is a refined naturalism to Moore’s line, smooth and poignant, as was the case with most of his work. Fellow animator Marc Davis would exclaim, “Fred Moore was Disney drawing [my emphasis]! We’ve all done things on our own, but that was the basis of what Disney stood for. It was certainly the springboard for everything that came after […] He never grew up, and that is what he animated.” The appeal in a drawing, its humor, its emotion, such was the mastery of Fred Moore. His ability brought something innate to each character in its form and movement. As Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston describe, “Fred’s great facility with his drawing fascinated everyone. It was uncanny the way he could put his line down with such accuracy- short lines or long flowing lines, it made no difference.”

Jiminy Cricket, perhaps the character who more than any other carries the heart of Pinocchio, was supervised by Ward Kimball. A close friend of Moore’s, Kimball would firmly establish himself with Walt as one of the Studio’s top talents in his work on Jiminy. In the pool hall sequence, “We see Jiminy at his huffiest,” as animator Eric Goldberg would later describe. Like Walt’s famous star, Donald Duck, Kimball’s animation yielded a Jiminy at his wit’s end, uncharacteristically truculent to both Pinocchio and Lampwick, yet nevertheless the recipe for abundant laughter. As Kaufman describes, “When Ward Kimball’s animation started to show up in sweatbox, Walt enjoyed it and urged intensifying it further: ‘He gets into the coat, just shaking- he can’t get in, he’s so damned mad.’ In the film the Cricket is so furious that he puts the coat on backward.”

Though Milt Kahl would later become perhaps the most respected and revered animator in the Studio’s ranks, he had only just begun to show his immense talent at the time of Pinocchio. It is Kahl whom we can credit as one of the key artists who contributed to the title character’s critical redesign early in production. As he’d later say in an interview with Christopher Finch and Linda Rosenkrantz, “I changed the conception, just forgetting the puppet aspect of him and handling him as a little cute boy. You would make him a puppet afterwards by putting in the joints and things…” In a period that was important as much for its artistic transitioning as for its innovation (as the two often go hand in hand), Kahl and Kimball were both part of the new generation that, beginning with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), was stepping up and beginning to rival in skill the so-called founders of the Disney style like Moore. By the end of the 1940s, this new generation had firmly established itself as the leading group of animators, whom Walt would later label as his “Nine Old Men.” As Kahl himself would say of Pinocchio, “That’s where I came into my own and became a senior animator.”

Like Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton of an earlier era, Kahl’s Pinocchio is hilarious in his expressive reaction to the cigar. As he takes a deep breath inward, Pinocchio’s blue eyes center towards his nose and the cigar below. As he swallows, the pupils dilate and begin to comically fill with water up to the brim until the irises become distorted and the liquid drains. The eyelids then sink low, covering half the pupil, seeming to sway listlessly about as the little wooden boy attempts to overcome his ailment and take a shot at pool. All this is taking place whilst Pinocchio’s skin changes color, accompanied by well placed sound effects and musical queues. It’s a moment to leave the audience laughing in the aisles. His failed attempts to hit the billiard ball come to a final hilarious climax as Jiminy shouts “Pinocchio!” upon discovering his charge, and the little wooden boy slices the queue through the green surface with a tremendous rip.

The magic of this sequence has much to do with the contrast of characters, often the key to interesting scenes of drama or comedy. Jiminy’s stouthearted declarations run headfirst into Lampwick’s cool confidence and poise, whilst Pinocchio’s timidity and reassured innocence seems set apart from either, the straight man to the humor of the scene’s other players. Neither character dominates the other, the result of beautifully paced editing and strong compositions of frame to accentuate each character’s role. The camera angle on Jiminy is low, as if we were lying atop the pool table. As the cricket finds himself on the floor below, the scene cuts to Lampwick, framed in a canted view above as he laughs somewhat repulsively and comically at Jiminy’s frustration. It’s all thanks to a superb team effort, beginning with the director, writers and story men, the voice artists, effects artists, background painters, inkers and painters, and editors. But the beauty of Walt’s animated art form was that it allowed this most collaborative of undertakings to give voice to moments of individual artistic genius. And in the case of this sequence, we have the likes of Fred Moore, Ward Kimball, and Milt Kahl to thank for it. This orchestration of talent was one of Walt’s greatest’s skills.

To discover more about Pinocchio, be sure to check out J.B. Kaufman’s incredible book, “Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic!”

Explore Wish Upon a Star: The Art of Pinocchio through January 9, 2017. This never-before-seen exhibition created by The Walt Disney Family Museum is being presented in the Diane Disney Miller Exhibition Hall.

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer, filmmaker, and contracting historian for the Walt Disney Family Museum.

Sources

-"Interview with Milt Kahl by Christopher Finch and Linda Rosenkrantz."Walt's People. Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him. Ed. Didier Ghez. Vol. 6. United States: Xlibris Corporation, 2008. 123-33. Print.

-Kaufman, J. B. Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic. San Francisco: Walt Disney Family Foundation, 2015. Print.

-Pinocchio Audio Commentary. Prod. Walt Disney. Perf. Leonard Maltin, Eric Goldberg, J.B. Kaufman. Walt Disney Studios, 2009. DVD.

-Thomas, Frank, and Ollie Johnston. Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life. New York: Abbeville, 1981. Print.