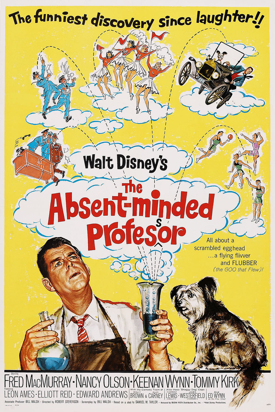

Throughout August, Walt Disney's 1962 live-action comedy The Absent-Minded Professor will be screened in The Walt Disney Family Museum’s state-of-the-art digital theatre at 1pm & 4pm daily, except Tuesdays, and Saturday August 13.

When you ask people about Walt Disney’s works, Mickey Mouse and Walt’s great animated films typically come first, then Disneyland, and for the older of us, the ritual of Walt’s weekly TV visit.

Seldom, though, is Walt mentioned as a maker of live-action films. Even more seldom is he acknowledged as the maker of a particular type of funny film—the “family comedy.”

But mention a few titles such as The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), That Darn Cat! (1965), The Ugly Dachshund (1966), or Blackbeard's Ghost (1968), and people’s faces often light up with both surprise recollection and fond memory. Even the most cynical filmgoers find something lovable about these peculiar and unique movies: “Disney’s escapist, harmless ‘family fun’ movies were everywhere in the 1960s,” writes Glenn Erickson on the web site DVD Talk, “and although we now sometimes wonder what attracted us to ’em, we sure loved them when we were 11 years old.”

Indeed, the ideas behind these movies were seemingly silly, or crazy, or outlandish. A flying Model T? An astronaut with an alien love interest? An olive garden workforce of chimpanzees? Hypnosis and mind-reading machines? A kidnapping with a clue-carrying cat?

One of the stars of several of these films (and similar projects made after Walt’s passing) was Dean Jones, who says, “The ideas were very, very audacious, unique, and everyone was vulnerable to the laughter they engendered.”

This series of films began with The Shaggy Dog, released in 1959. Based upon the novel The Hound of Florence by Felix Salten (whose books Bambi: A Life in the Woods and Perri: The Youth of a Squirrelhad already been adapted to film by Walt), the property had initially been brought to ABC as a television project. When Walt brought the property to the Network, during a yearlong period whenwunderkind James T. Aubrey was head of Programming, the executive was blatantly dismissive—even excusing himself from the meeting after Walt’s pitch. Unperturbed, Walt decided to make the project a feature film—and it turned out to be the highest-grossing film of the year.

“The Shaggy Dog was sold as a hip teenaged monster movie that added to its family appeal by bringing out the crowd that came to 50s monster films just to laugh at them,” Glenn Erickson writes. “Disney was the first major filmmaker to see that a picture about a shape-shifting teenager would make a natural comedy.”

As successful as it was, Walt’s next live-action comedy came a full three years later. When The Absent-Minded Professor was released on March 16, 1961, critics raved about its lighthearted humor, clever situations, and inventive special effects. It was nominated for three Academy Awards®; for Special Effects, Art Direction, and Cinematography. Fred MacMurray was also nominated for a Golden Globe Award for best actor in a musical/comedy.

Dean Jones recalls, “I remember when I took my two kids to see The Absent-Minded Professor––I had never seen a Disney picture. I had seen the documentaries, the migration of the elks, that sort of thing. But Walt asked me one day, ‘What kind of films do you want to make?’ and I said, ‘Well, how about Walt Disney pictures?’ He said, ‘A boy and his dog?’ and I said, ‘No, films that make the whole family laugh.’ I told him I had seen…The Absent-Minded Professor. ‘I took my kids because I thought it was a kid picture,’ I said. ‘I was laughing at the audacity of what you were doing; it was very amusing to me. I always saw your pictures, and I see these films that I’m doing now, as very tongue in cheek. Very satirical in some ways, very poking-fun in other ways.’”

The engine behind both of these films was an ingenious writer/producer named Bill Walsh. Born in New York to immigrant parents. In his teen years he lived with relatives in Ohio and later attended the University of Cincinnati. In 1933 he joined the stock touring company of husband and wife team Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay. The couple divorced the following year, and Walsh wound up working as a publicity agent. Walsh joined The Walt Disney Studios in 1943, working for both the Publicity and Story departments. He brought his former client Edgar Bergen to Disney for Fun and Fancy Free in 1947, and impressed Walt with his talent and savvy, so much so that Walt chose Bill to head the studio’s new television division. When Disney made a deal with ABC Television for a kid’s TV series called The Mickey Mouse Club, Walsh was named the series’ producer.

After three years of five hour-long shows a week, Walsh was understandably weary, and moved into a less demanding role as writer/producer, a job that he would hold at the Studio until his death in 1975. His films are numerous and fondly remembered, including Toby Tyler, or Ten Weeks with a Circus (1960), Bon Voyage! (1962), Son of Flubber (1963), Mary Poppins (1964), That Darn Cat! (1965), Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. (1966), Blackbeard's Ghost (1968), The Love Bug (1968), Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971), The World's Greatest Athlete (1973), and One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing (1975).

Walsh wrought imaginative and intelligent scripts that were smart and funny while staying in touch with one of Walt’s fundamental self-perceptions. “I can’t laugh at intellectual humor, you know?” Walt said. “I want to be hit here. I’m just corny enough. I want to be hit right here in the heart.

Dean Jones ran into this humble sense of humor on a film with Walt. “I had tried to get some gags that I thought were corny out of one of the pictures, and he said, ‘That gag was funny in 1923 and it’ll be funny today,’ and he was absolutely right. He kept it in the picture, he didn’t listen to me, and I laughed at the premiere along with the rest of the audience.”

As for Walt himself, he simply saw these films as an inspiration from his own screen heroes. “I love to build these comedies because I was a great fan of Chaplin, of Lloyd, I loved those things. They’re not being done today. So, in effect, that’s what I’m doing. The Absent-Minded Professor is in effect, like a very good [Harold] Lloyd or Chaplin picture. It’s more like a Lloyd picture because Lloyd always had these kind of situations. Chaplin was more the individual. I love to do those and I want to do more of them.”

Have you ever wondered how Walt Disney learned about comedy? As Walt Disney was growing up, he saw—and was inspired by—the work of the great silent screen comedians. On Saturday August 13 at 3:00pm, learn from Disney Authors and Historians J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt about how comics such as Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton influenced Walt's works in the program Comedic Influences with J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt. Tickets are available at the Reception and Member Service Desk at our museum, or online at www.waltdisney.org.

Images above: 1) © Disney. 2) Fred MacMurray explains the principles of Flubber to Charlie. © Disney. 3) © Disney.