This month we celebrate the Season of Giving, and the generous legacy of Walt Disney. Not simply the films and entertainment that Walt gave us, or even his generosity to the community and numerous charitable organizations over his lifetime—we celebrate the bounty of Walt’s influence in many areas of our culture around the world, a true “gift that keeps on giving,” even today—110 years after his birth.

“Now, to tell you the truth,” Walt Disney said, “I was never a good artist. I was never satisfied with what I did, but it was a means to an end.” For a man who maintains a reputation as one of the world’s great artists, that thought is both a humble one, and an explanation of the place of art in his life.

Walt had always been interested in drawing, even in his childhood. He recalled, “…I had an Aunt that was a very favorite aunt who would come and visit us. Her name was Aunt Margaret. She’d always bring something for my sister and she’d bring me a big tablet and these Crayola things. I was always drawing Aunt Margaret pictures. And she’d just rave over them, and she’d keep them.”

As he began his adult life, he gravitated to the commercial applications of his avocation. During his service in the Red Cross, he spent his off hours drawing, “I was doing drawings then and I sent them into Life and Judge,” he said, “I had my drawing board right by my bunk. The guys would throw me ideas. I’d draw them up. We’d all wait for the next issue. It wouldn’t be in.”

As he began his adult life, he gravitated to the commercial applications of his avocation. During his service in the Red Cross, he spent his off hours drawing, “I was doing drawings then and I sent them into Life and Judge,” he said, “I had my drawing board right by my bunk. The guys would throw me ideas. I’d draw them up. We’d all wait for the next issue. It wouldn’t be in.”

As he returned home and his career progressed through early work in advertising and the infant animation medium, Walt gained more experience and skill (and the surviving work proves that he was a better draftsman than he gave himself credit for in later years), but he was also aware both that there were more accomplished and efficient artists around him, and that his creative desire had a breadth that extended well beyond the drawing board.

After founding his own Studio, he focused on the application of artistic talent to production need as well as creative visions that he had for his filmmaking. “The first thing I did when I got a little money to experiment, I put all my artists back in school,” Walt proudly recalled. “Art schools that existed then didn't quite have enough for what we needed. So we set up our own art school.” Walt hired Don Graham of the Chouinard Art School in Los Angeles who spent nearly a decade studying the challenges presented by animation and teaching Walt’s team, focusing the animators’ attention on “action analysis,” and ways to convert two-dimensional graphics into the illusion of moving three-dimensional action. (He did research on the significance of animation as a graphic form, which became the material for studio reference materials and the forerunner of his classic 1970 textbook, Composing Pictures).

In 1950 Walt engaged Don to investigate the possibilities of making films on various aspects of art. Dividing his time between Disney and Chouinard, Don's research intended as a film eventually ended as a component of Bob Thomas's 1958 book, The Art of Animation.

At about the same time, as Walt entered the nascent field of television, he made the (correct) assumption that his viewers would be interested in not only the Disney product, but also in the artistic effort, technique, and principles behind the work. Several of hisDisneyland television programs featured fairly thorough views of art techniques, including “The Story of the Animated Drawing,” “Tricks of Our Trade,” and “The Plausible Impossible;” his program “An Adventure in Art” uses Robert Henri’s 1923 book The Art Spirit as it’s through-line, and contains a fascinating segment featuring four of the Studio’s disparate artists each painting the same tree.

Author and animation historian Michael Barrier notes that “certainly [The Art Spirit] has echoes in the studio’s practices in the thirties and forties. Henri speaks of brush strokes, for example, in terms that evoke the best drawn animation: ‘Strokes which move in unison, rhythms, continuities throughout the work; that interplay, that slightly or fully complement each other.’”

As was frequently the case, as art and artists continued to be vital in Walt’s life, and as he maintained lengthy and deep friendships with so many artists, the notion of carrying forward the artistic spirit and collegiality that had been so deeply engrained in the Studio culture began to take shape as a whole new notion, and yet another generous legacy.

As was frequently the case, as art and artists continued to be vital in Walt’s life, and as he maintained lengthy and deep friendships with so many artists, the notion of carrying forward the artistic spirit and collegiality that had been so deeply engrained in the Studio culture began to take shape as a whole new notion, and yet another generous legacy.

In 1960, Walt began plans for a new school for the performing and visual arts, where different disciplines commingle under one roof. The following year, Walt and Roy helped guide the merger of the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music (founded in 1883), and the Chouinard Art Institute (founded in 1921), to form California Institute of the Arts. The Disney brothers worked tirelessly with Lulu May Von Hagen, chair of the Conservatory.

In 1964, after receiving accreditation from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, California Institute of the Arts was introduced to the public by Walt Disney at the Hollywood premiere of Mary Poppins, which was a fundraiser for the new school. The short film, The CalArts Story, specially-produced by Walt Disney Productions, was presented prior to the feature film.

The original concept presented by Disney envisioned the CalArts campus in the hills on the Cahuenga Pass adjacent to the Hollywood Bowl, but when this location later became unavailable, the campus was re-sited to Valencia, 30 miles north of downtown Los Angeles.

Today, California Institute of the Arts houses six schools—Art, Critical Studies, Dance, Film/Video, Music, and Theater—and offers internationally acclaimed degree programs across the range of visual, performing, media, and literary arts. CalArts also operates the Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater (REDCAT) in the Walt Disney Concert Hall complex located in downtown Los Angeles, and leads the county-wide Community Arts Partnership (CAP) youth arts education program.

Throughout his career as a creative innovator, Walt Disney was dogged by the demons of public perception. “I’ve been criticized many times for being an artistic success and a commercial failure…then from another set of critics I was…all commercial, and anything artistic was purely coincidental, you know?”

Fortunately, critics are not the final arbiter of any artist’s creative influence; and the impact of Walt Disney in the art he created, the artists he influenced, the art he inspired, and the teachings of his art have the final statement of the value of his artistic legacy.

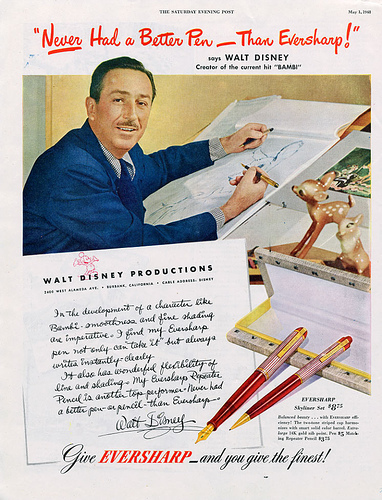

Images above: 1) Walt self-depicted as an artist on his first business card. Courtesy of the Walt Disney Family Foundation. 2) Walt's public identity as an artist never faded. Courtesy of the Walt Disney Family Foundation.

On December 10, Pixar's Academy Award®-winning director Pete Docter and producer Jonas Rivera, and Walt Disney Animation Studios' Andreas Deja will visit The Walt Disney Family Museum for an examination of the way Walt Disney's perspectives and passions forever impacted the entertainment industry around the world and across the media. The three filmmakers will converse with host and moderator Jeff Kurtti about how Walt's vision and creativity continues to influence our culture today—and how he has been a vital stimulus in their own work.