In 1935, Walt Disney was at the peak of his short film production. Mickey Mouse would make his color debut in The Band Concert, followed by a string of wonderfully executed shorts including Pluto’s Judgement Day. With the Silly Symphonies series, Walt won an Academy Award® for The Tortoise and the Hare, and later in the year classics such as Music Land and Three Orphan Kittens would premiere. But it was in June that one of the boldest Disney films was released. Who Killed Cock Robin? was like no other Disney film that came before or after. And it remains a strikingly powerful piece of storytelling and design.

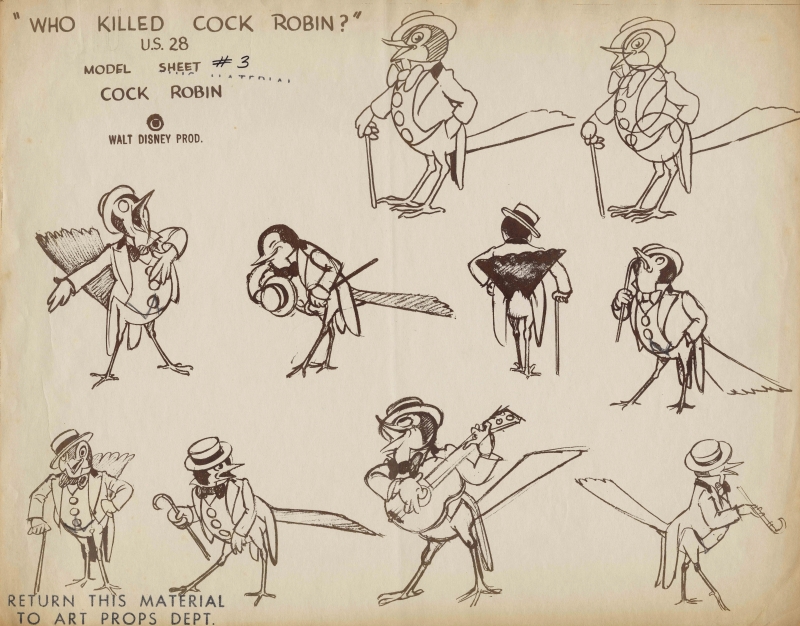

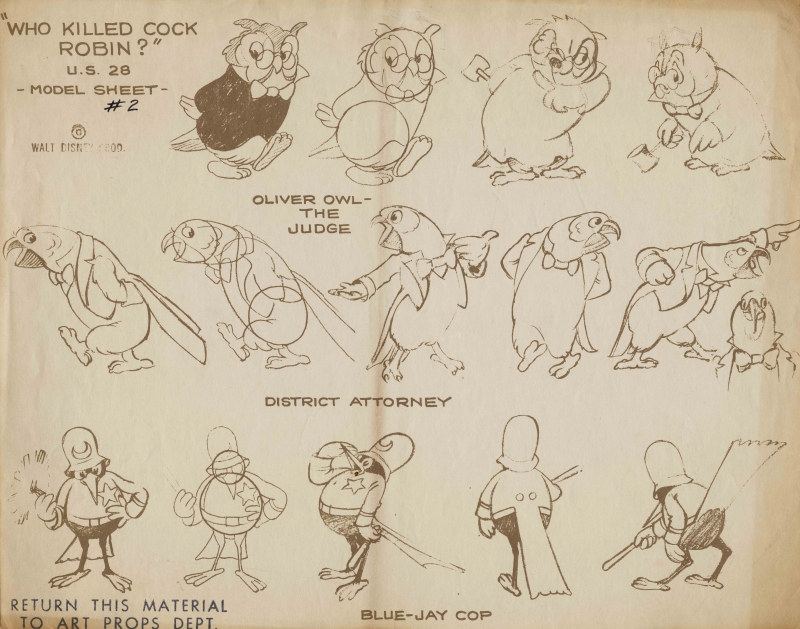

Musically driven like the other Silly Symphonies, Who Killed Cock Robin? is told as an operetta. In a world where birds are personified, young Robin is busy serenading Jenny Wren on a moonlit night. An unknown assailant, seen only in a highly cinematic use of shadow, shoots Robin with an arrow. He falls dramatically and seemingly to his death. The community gathers feverishly around his body as a violent police force disperses the crowd. The following day a trial is held, where an imposing owl serving as the judge, oversees the proceedings. A contemptuous parrot is the prosecutor, who attempts to force a confession out of multiple witnesses. The jury, acting as a chorus, remains suspicious of everyone. Only after Jenny Wren’s testimony do we discover that our assailant is in fact Cupid himself, and Robin, now awakened, was shot with an arrow of love!

The Death and Burial of Cock Robin, originally published in 1744, was one of many nursery rhymes collected by the Disney story team for use in their films. Director Dave Hand delegated story development to writer Bill Cottrell and artist Joe Grant, which took place from March through November of 1934. Cottrell and Grant proved one of the best story partnerships of the 1930s, and Who Killed Cock Robin? was their biggest success. “We got into more high class stuff,” Grant would say. “We were really on our way.”

Joe Grant had a background in celebrity caricature, and originally came to the Walt Disney Studios for such a role on the short, Mickey’s Gala Premier (1933). Though multiple Disney films, such as the one just mentioned or Mickey’s Polo Team (1936) featured the use of caricature, the application of Who Killed Cock Robin? was more as if the subjects themselves were taking on a role in the story, and not just simply being lampooned. Cock Robin himself croons like Bing Crosby, the cuckoo resembles Harpo Marx, and most notably Jenny Wren is clearly based on Mae West. It’s important to remember that these resemblances would’ve been far more recognizable by the contemporary audience in 1935. Writer Robert Feild commented less than a decade later, “So technically proficient, so competent in draftsmanship had the artists in the Studio become, that now they need not hesitate to caricature living individuals. Here was satire in its richest vein. What chance had Judge Wudgey as Jenny Mae strutted her stuff beneath the unwise gaze of the old owl?”

The story of Who Killed Cock Robin? is “uncharacteristically satirical,” as historian Michael Barrier describes. The story is dark, if not a little sardonic in nature. The woodland setting of a community of birds is a tough, gritty, 1930s world where characters fight and carouse and the police are abusive. The courtroom drama that ensues after Cock Robin’s supposed murder is cynical and over-dramatized. “We don’t know who is guilty, so we’re going to hang them all!” the jury proclaims.

Though this was newer territory for Disney, the film is as delightfully entertaining as any of the other, lighter Silly Symphonies. The operetta style of the film serves to “soften the satire’s sting,” as Barrier describes, and “the resemblance to Gilbert and Sullivan is unmistakable.” Norman Ferguson masterfully animates the judge, whose billowing voice courtesy of Billy Bletcher remains etched in one’s memory (Bletcher was also the voice of Mickey Mouse’s nemesis, Pete). Bill Roberts’ animation of the District Attorney parrot is extreme and forceful, perhaps later inspiring Ollie Johnston in his own animation of the lawyer from The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949).

Walt himself would describe the art of animation as “caricatures of life,” and Jenny Wren is a fine example of how the caricature can influence the entirety of a character’s design and production. As historian John Canemaker comments, “[…] Grant had learned to create flexible freely moving forms. Grant used bird anatomy selectively to bring forth Mae West…[and his] eye-appealing animation designs registered strongly with Disney.”

Animator Ham Luske made new lengths in his animation of Jenny, carrying Grant’s caricature into his drawing. As Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston would later describe, “ […] through careful study [Ham] had pinpointed what made her Mae West: the provocative swaying walk with the slow shifting of weight, the characteristic way she rolled her eyes and talked out of the side of her mouth… She, like the real Mae, seemed to have appraised the situation, sized up the opposition, and was in complete control…no animator had ever done anything like it before.” Mae West herself would write to Walt in admiration of Luske’s animation. It remains one of the smoothest and most poised performances in the Disney canon.

Actress Martha Wentworth provided Jenny’s voice, which is naturally an impression of West’s iconic delivery and wit (interestingly, Wentworth later provided the voice of the Nanny in One Hundred and One Dalmatians [1961]and Madame Mim in The Sword in the Stone [1963]). West had a kind of dignified yet gritty quality that was accurately captured in Wentworth’s performance.

Historians J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt write, “In this seven-minute cartoon…generic formulas are seamlessly braided together. The famous nursery rhyme has been turned into a pre-noir crime story… But the film is also constructed like a miniature musical comedy…” There is brilliance in this complex blending of styles unique to this picture. In many ways, Walt would never produce such a bold short film again.

With all the fearless, ever-confident strides being made from film to film during this period, it was no wonder that production on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) officially began around the same time. With the polished execution of Who Killed Cock Robin? in particular, Walt knew that his artists were ready for a bigger challenge.

Lucas O. Seastrom

Museum Educator and Content Developer at The Walt Disney Family Museum

Sources

- Barrier, Michael. "Disney, 1933-1936." Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. 134-36. Print.

- Canemaker, John. Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft. New York: Disney Editions, 2010. Print.

- Feild, Robert D. The Art of Walt Disney. New York: Macmillan, 1942. Print.

- Finch, Christopher. The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdoms. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2004. Print.

- Maltin, Leonard. Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. New York: New American Library, 1987. Print.

- "Martha Wentworth." IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 08 June 2015. <http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0921131/>.

- Merritt, Russell, and J. B. Kaufman. Walt Disney's Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series. Gemona (Udine), Italy: La Cineteca Del Friuli, 2006. Print.

- Thomas, Frank, and Ollie Johnston. The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. New York: Hyperion, 1995. Print.

Sincerest thanks to J. B. Kaufman for his support in developing this article!