Novice Trivia

- 1958

-

1918

-

Virginia

-

Switzerland

-

Snow White

-

Bambi (1942)

-

Carmen Miranda

-

Carousel

-

"it's a small world"

-

Lillian

Expert Trivia

-

Fantasia (1940)

-

1900

-

Felix the Cat

-

Sugar Bowl

-

Dopey

-

Animator

-

El Grupo

-

Disneyland

-

Sleeping Beauty

-

1941

Key to the City of San Francisco

Walt was no stranger to the city of San Francisco or the greater Bay Area, visiting the region numerous times throughout his career. Over the years he visited the region to attend such events as the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939 and the San Francisco premiere of Fantasia (1940) at the Geary Theater.

On December 10, 1958, Mayor George Christopher presented Walt and Lillian Disney with the Key to the City of San Francisco. One of the unique threads connecting Walt Disney with San Francisco is this Key to the City. The back of key says "Please Come Again"—an offer that the Disney family took to heart in opening The Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco in 2009.

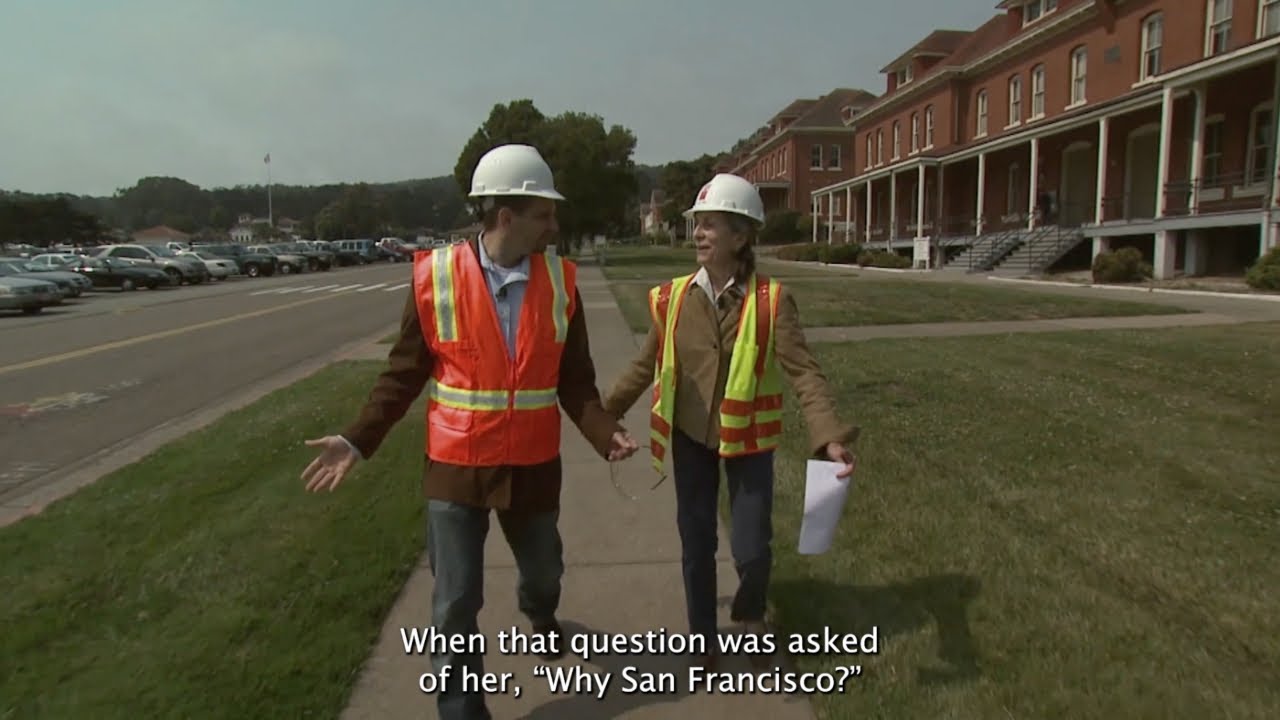

Guests often ask why The Walt Disney Family Museum is located in San Francisco. Here is an excerpt from The Walt Disney Family Museum documentary film featuring museum co-founder and Walt Disney’s daughter, Diane Disney Miller, explaining the significance of the museum’s location:

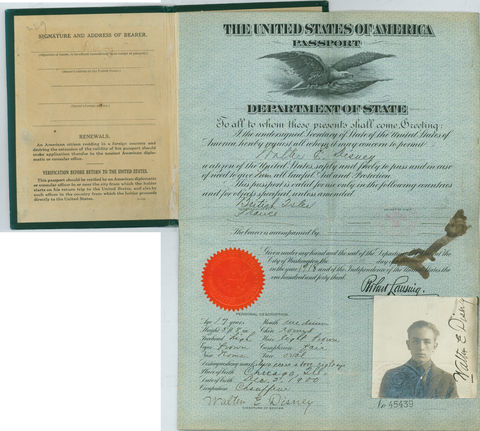

Passport

When World War I began, Walt was determined to serve his country, like his older brothers who enlisted. At 16, he was too young for the armed forces, but he found that the American Red Cross Ambulance Corps would take 17 year old volunteers, as long as his parents approved. His mother preferred to know where he was going than to have him run off. He forged the document his mother signed—inflating his age by a year—allowing him to join the cause and travel to France. “My mother made this affidavit out that her son Walter Elias Disney was born December 5, 1901, and this and that and she gave permission and… signed it. She put it down and she’d…no more turned her back then I picked up the pen and from the ‘1’ I made a ‘0’.” Walt’s official 1918 passport listed his birthday as December 5, 1900.

In 1956, Walt Disney sat down with Saturday Evening Post journalist Pete Martin and his daughter Diane Disney Miller to share stories of his life to be featured in an eight-part series titled, “My Dad Walt Disney.”

Here is an exclusive audio clip of Walt Disney telling the story of altering his 1918 passport.

Walt: “Yeah, that was a great war for volunteering, you know. We finally had the draft but there was a terrific amount of volunteering in that war. I was a cadet in high school, and I got a certain amount of cadet training. So, in 1918 I tried to join. So finally, this kid come in to me very excited and he says, ‘there’s something just forming here that you and I can get in.’ He said, ‘They don’t care if you’re too young,’ you know. I said, ‘What is it?’ And he said, ‘an ambulance unit.’ We went down and we went down and signed up. We found out that we had to get parents’ signatures, and we had to get passports because we were not officially part of the army. This was a volunteer unit.

“I went out and told my mother I wanted her to write out a permission thing and my father was against it. My father said, ‘I will not sign any permission.’ He said, ‘It’s signing a death warrant for my son.’ And he said, ‘I'm not…’ and my mother said, ‘Elias, the boy is determined’” And she says, ‘I would rather sign this and know where he is than have him run off somewhere.’ And my father said, ‘Well you can sign it. And you can sign it for me, but I won’t.’ So my mother made out this affidavit.

“Well, I was still a year too young. I was sixteen. They’d take you by seventeen. My mother made this affidavit out that her son Walter Elias Disney was born December 5th, 1901, and this and that and she gave… and they gave permission, and both signed it. She put it down and she’d just no more’n turned her back then I picked up the pen and from the one I made a zero.”

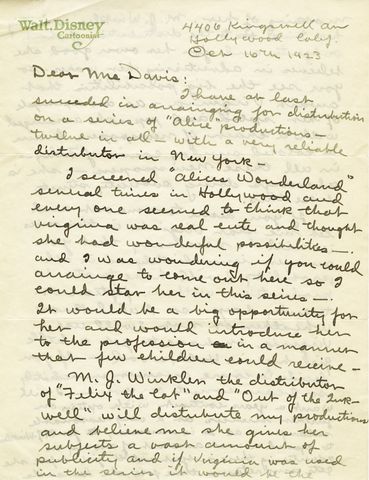

Letter to Mrs. T.J. Davis

Walt traveled to Hollywood in 1923 with one last film project from his time in Kansas City, a pilot cartoon short—Alice’s Wonderland (1923)—featuring a live-action girl in an animated Cartoonland, performed by Virginia Davis. Walt contacted one of the biggest cartoon distributors of the day, Margaret J. Winkler of Winkler Pictures, about the film. On October 16, 1923, Walt and Roy O. Disney established the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio when they signed a contract with Winkler for distribution of an initial series of Alice Comedies short films. She specified in her original telegram that Alice had to be played by the same little girl in the unfinished pilot reel. On that same day, Walt wrote this letter to Virginia Davis’ mother.

On October 16, 1923, Walt wrote a letter to Mrs. Davis asking for the family to move from Kansas City to Hollywood so her daughter Virginia Davis could star in the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio’s new series, the Alice Comedies. In the letter Walt wrote, “I screened Alice’s Wonderland several times in Hollywood and everyone seemed to think that Virginia was real cute… Was wondering if you could arrange to come out here so I could star her in this series. It would be a big opportunity for her and would introduce her to the profession in a manner that few children could receive.”

Virginia Davis’ father agreed to leave his job in Kansas City and move his family to California. Walt promised to pay his star $100 a month, making Virginia Davis the studio’s highest paid employee.

Virginia Davis would go on to star in 13 short films as part of the Alice Comedies series.

Here is an excerpt of an interview with Davis where she recalls receiving this letter from Walt in 1923.

Virginia Davis: “When I was age four, a letter came from California, my mother was very excited about it.She didn’t say much to me, just that we were going to go to California. There were two different things in there, the letter said that that he had this Alice’s Wonderland was okay’d and he had gotten a distributor—M.J.Winkler as a matter of fact. He thought that would be terrific for me and he proceeded to do a great selling job in the letter to my mother, that it would be a great opportunity for Virginia. And so forth and so on.”

Who is M.J. Winkler?

Margaret J. Winkler was the first female member of the Motion Picture Producers Guild. Cleverly establishing herself in the industry as “M. J. Winkler,” she started her own company—M.J. Winkler Productions—to produce and distribute animated cartoons. She handled the promotional campaigns, press releases, advertising, and full distribution of animated short subjects. She went on to popularize and revitalize the cartoon character Felix the Cat.

Margaret J. Winkler was the only female leader in the male-dominated world of movie distribution at the time. At the helm of Winkler Pictures, she established animation as a sustainable division of the entertainment industry and played a key role in the start of what we know today as The Walt Disney Company.

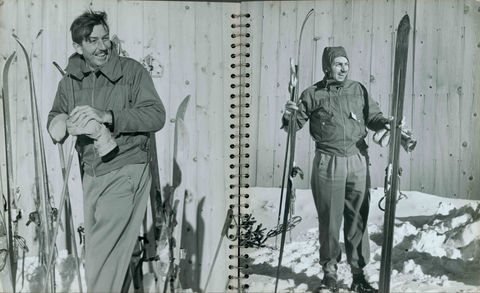

Walt's Skis

Walt took up skiing in the mid-1930s on skis similar to these Attenhofer downhill skis. Late in that decade, Walt met Austrian Olympic skiing champion Hannes Schroll, who was the head of the Yosemite Ski School. The two became good friends. In 1938, Schroll and his business partners purchased land in the east Sierras, with the intention of building a ski resort near Donner Peak and the small town of Truckee, California.

Schroll had sought financial assistance from Walt in building the resort that eventually became Sugar Bowl Resort in Norden, California. To honor Walt’s support and partnership, Schroll changed the name of Hemlock Peak to Mount Disney.

Enjoy this exclusive interview from Diane Disney Miller, daughter of Walt Disney and co-founder of The Walt Disney Family Museum, as she shares her memories from ski trips during her childhood alongside home movies of their winter holidays. This audio is an excerpt from Christmas with Walt Disney (2009), now available to stream on Disney+.

Cartier Jewelry

In 1937, Cartier, Inc. partnered with Disney to produce a charm bracelet with the likeness of Snow White and each of the Seven Dwarfs. Photographs of Walt and Lillian at the premiere of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) at the Carthay Circle Theatre on December 21, 1937, show Lillian wearing this Cartier bracelet.

At the time, these were some of the most exclusive products from the vast array of merchandise that was created for the film. Time and again, Lillian would wear many similar tributes to Walt’s achievements.

An ambitious and forward-thinking merchandiser by the name of Kay Kamen was responsible for the tremendous line of licensed Disney character products, beginning in 1932. By the time Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was released, an extensive line of merchandise already existed, offering an array of products developed around Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, the Three Little Pigs, and others.

Kamen viewed the holiday release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs as a lucrative opportunity to market many of the products as gift items. Some of the licensed products developed for the film included neckties, linens, radios, shoes and slippers, puppets, wind-up toys, baby rattles, jewelry, records, and sheet music.

In the 1938–39 catalog, Kamen articulated the extensive reach of the line of Disney products: “Demand for this merchandise has grown to such an extent that it has become of signal importance, not only to retail institutions everywhere, but to American industry as a whole… all volume records for Disney character merchandise have been broken.”

Kamen was also concerned with the quality of the products being developed in conjunction with Disney entertainment. Just as Walt’s films were considered to be some of the highest quality in the entertainment industry, Kamen wanted the character merchandise to uphold a similar standard of superiority: “…all of this implies a responsibility and a duty beyond the strictly commercial aspects of our association. We must dedicate our efforts toward a constant maintenance of the high quality which makes all of this possible.”

In 1956, Walt Disney sat down with Saturday Evening Post journalist Pete Martin and his daughter Diane Disney Miller to share stories of his life to be featured in an eight-part series titled, “My Dad Walt Disney."

Here is an exclusive audio clip of Walt Disney telling the story of Snow White’s reception in Hollywood.

Walt: “In December, we had a big premiere at the Carthay Circle Theater. Big grand Hollywood premiere. And all of Hollywood brass turned out for a cartoon. That was the thing. And it went way back to when I first came out here and I went to the first premiere. I’d never seen one in my life. And I went down, and I saw all these Hollywood celebrities comin’ in and I just had a funny feeling there. And I just said maybe someday they’ll be going into a premiere of a cartoon because people would appreciate the cartoon medium. But it was an exciting thing to have that premiere.”

Retta Scott Artwork

Retta Scott was the first female animator to be given a screen credit in a Disney film. Scott started working at the Studios in 1939 in the Story Department on Bambi (1942). Her charcoal sketches of the powerful sequence where Bambi faces a pack of hunting dogs caught the attention of Walt and the production team. As Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston later described, “A startling moment for us came when we saw Retta Scott’s amazing sketches of the vicious dogs…” She described her work noting, “My director Eric Larson gave me much encouragement and guidance. As I only have been working on the dogs, Eric felt that I should clean them up where needed. I estimated that during that year I had drawn over 56,000 dogs for Bambi.”

As Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) approached completion, Walt began to consider other potential feature-length stories and settled on adapting Felix Salten’s book Bambi: A Life in the Woods. Bambi was planned as the second Disney feature and serious story work started in spring 1937. The film’s mounting artistic and technical challenges delayed production, and it was not completed until 1942.

Inseparable from the development of Bambi (1942) is the new training program implemented for the animators to enhance the sophistication and realism of their art. Starting in 1932, Walt brought on Don Graham from the Chouinard Art Institute to set up an art school at the studio. The impact of the training program can be felt in the progression of Disney short films throughout the 1930s and their earliest feature films.

An early emphasis of the training program was for Walt’s artists to get a better handle on human anatomy, but for a film like Bambi, the ability to realistically capture animal anatomy was paramount. Field trips were made to the Los Angeles Zoo to study the animals. Walt hired notable animal painter Rico Lebrun to lecture at the studio for six weeks.

According to Bob Thomas’ book, Walt Disney: An American Original, The Maine Development Commission provided two live fawns for the studio artists to study as they grew. Rabbits, ducks, skunks, and owls were added to the studio training program. From an outsider, it would have looked like a small zoo had taken over The Walt Disney Studios.

In 1956, Walt Disney sat down with Saturday Evening Post journalist Pete Martin and his daughter Diane Disney Miller to share stories of his life to be featured in an eight-part series titled, “My Dad Walt Disney."

Here is an exclusive audio clip of Walt Disney sharing his thoughts on the production of Bambi.

Walt: “Bambi was on that we had a little trouble starting because we had the book, and we were trying to retain certain things from the book. And it was quite a fight there until we finally decided that there were many things that were not right for our medium, and then we made the changes. And when we finally got our own little plan for Bambi, why, we began to roll, we had a lot of fun with it.”

“After an intensive course in the human anatomy and locomotion, we then went into animal. Now you know animal anatomy is a thing that very few artists ever get anyway. And before I started Bambi, we had been doing these little cartoon animals. But Bambi they had to be a little closer to the real animal, it’s a caricature with certain little humanized touch. But still believable as deer and as animals in the forest. So the backgrounds for that was a good study of animal anatomy and how deer and how all these other animals actually reacted.”

Diane's Brazilian Doll

Prior to the United States' entry into World War II, President Roosevelt initiated the Good Neighbor policy to strengthen ties between the country and the republics of Central and South America. To foster goodwill between the nations, Hollywood producers were asked by the US government to incorporate Latin American themes and talent into their films and asked Walt to undertake a personal tour as well. In the fall of 1941, he, Lillian, and a handpicked group of studio personnel made a goodwill tour of South America, where they gathered artistic impressions of Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and other countries for use in a series of Good Neighbor Policy-related films.

After months away, Lillian and Walt returned to their daughters with gifts in hand. Diane received a Lenci Doll Company doll depicting popular Brazilian actress Carmen Miranda that stood 36 inches tall, which at the time was around the height of eight-year-old Diane. Sharon, in turn, received a Baiana doll. Internationally, Carmen Miranda popularized Baiana style and became known for her fruit-adorned headwrap.

In this special audio clip, hear from Diane Disney Miller, daughter of Walt Disney and co-founder of The Walt Disney Family Museum, about receiving this special doll.

This audio is an excerpt from Christmas with Walt Disney (2009), now available to stream on Disney+.

Diane: "The South America trip made a big impression on both Sharon and me, she was very little...They were gone for three months, and they didn’t come home until it was almost Christmas time actually...

"Their welcoming home, it wasn’t our Christmas gift, but I got this wonderful doll. I learned later it’s a Lenci Carmen Miranda doll. It was about as big as I was, and the doll is in our museum. It’s a little worse for wear because it was in storage for a long time."

Griffith Park Bench

Saturdays were “Daddy’s Day,” and included regular trips with his daughters Diane and Sharon to Griffith Park to ride the merry-go-round. Walt remembered, “[Disneyland] came about when my daughters were very young, and Saturday was always Daddy’s Day… I’d take them to the merry-go-round… and as I’d… sit on a bench… I felt that there should be something built… where the parents and the children could have fun together. So that’s how Disneyland started… But it all started from a daddy with two daughters wondering where he could take them where he could have a little fun with them, too.”

This bench is original to Griffith Park, where Walt dreamed up Disneyland. This bench was gifted to Diane Disney Miller by Griffith Park during a renovation of the park. Another of the Griffith Park benches is located in Disneyland in the Opera House lobby.

In 1956, Walt Disney sat down with Saturday Evening Post journalist Pete Martin and his daughter Diane Disney Miller to share stories of his life to be featured in an eight-part series titled, “My Dad Walt Disney.”

Here is an exclusive audio clip of Walt Disney sharing the story of dreaming up Disneyland.

Walt: “Disneyland the idea for a Disneyland laid dormant for all those years. It came along when I was taking my kids around to these kiddie parks. I’d take them out. And we used to go out, I mean every Saturday and Sunday. Their mother wouldn’t go with us. We’d be gone. I took ‘em to zoos, I took ‘em everywhere. And they used to love to go with me in those days. And those were some of the happiest days of my life.

“While they were on the merry-go-round riding 40 times or something, you know. I'd be sitting there tryin’ to figure what you could do and when I built the studio over there I thought well, gee we ought to have a really a three-dimensional thing that people could actually come and visit.

“So I had a little dream for Disneyland adjoining the studio. But I kept working on it and I worked on it with my own money. Not the Studio’s money, my own money.”

Walt's Bronzed Hat

Walt’s beloved hats were often the subject of laughter and fun. Much to his wife Lillian’s dissatisfaction, Walt often wore hats at a jaunty, rakish angle. When Lillian asked Walt to “fix” his hat, he would often respond by crushing the hat on his head, which would cause Lillian to playfully take the hat from him altogether. In an ode to this back and forth, Walt presented Lillian with a very special gift on her birthday, February 15, 1941.

At first, Lillian thought Walt had given her a lovely arrangement of orchids, but, when she lifted the flowers from their “vase,” she found Walt’s favorite hat. The crown had been pressed into the shape of a heart and the entire hat had been preserved in bronze. Walt had finally done what Lillian had asked—he permanently fixed his hat! For Walt, the bronzing of his hat symbolized the ways in which his and Lillian’s laughter and love withstood the test of time.

In 1953, Lillian Disney sat down with McCall’s magazine writer Isabella Taves to pen the article, “I Live with a Genius.” In the article Lillian shares insight into being married to Walt and raising their two children, Diane and Sharon. Here are some excerpts from the article:

“I wouldn't have missed one minute of the 27 years I have been married to Walt Disney. I'm proud of my husband and what he has done—but I'm even prouder that along the way, in bad times and good, he has never lost his sense of humor or his zest for life.

“Being married to Walt Disney is never dull. There have been plenty of times when I felt as though I were attached to one of those flying saucers they talk about. Despite all our apparent security—Walt's big studio and our Hollywood home and our smaller place in Palm Springs—I never know when Walt's imagination is going to take off into the wild blue yonder and everything will explode...

“Being female, I maintain that Walt's imagination flies so high he naturally sees a little farther than the rest of us But, although Walt has been right a number of times when we have been wrong, we don't encourage him by admitting how smart he is to his face. We work on the premise that Walt may be a genius but any genius, especially Walt Disney, is wild-eyed and needs a practical family to watch over him...

“Some years ago, I had been hounding him about a disreputable old hat he insisted on wearing. Walt has excellent taste in clothes, but he won't take care of them. He ruins every suit he owns by coming through the kitchen when he gets home at night and filling his pockets with bologna and hot dogs for our nine-year-old French poodle, Dee-Dee. What he does with his hats I don't know, hut something equally gruesome.

“Finally, the disreputable hat vanished. I didn't ask where—I was too pleased. But it turned up again on my birthday. Walt had had it copperplated—the process they use on baby shoes to preserve them—and then filled it with brown orchids. It hangs in our projection room, and I feel very sentimental about it.”

Alice Davis Costume Designs

Alice Estes’ reputation as a fashion designer preceded her. One day, to her surprise, she received a call from her former animation instructor, Marc Davis, at The Walt Disney Studios asking her to design a dress for the live-action model of Princess Aurora for then in production animated feature Sleeping Beauty (1959). Tom Staggs, former chairman of Walt Disney Parks and Resorts, spoke on the spark between the two artists during the production of Sleeping Beauty: “That [Sleeping Beauty] costume was exactly what [Marc] was looking for—and so was Alice.” The two artists married in 1956.

Years later, Alice Davis got another very important phone call from Marc. “Alice, Walt wants to know if you’d like to do the costumes for ‘small world.’” Alice shared, “I designed all of the costumes and the patterns and the choice the fabrics and so on. I was working with Mary Blair, and she was setting the colors that she wanted to go with the sets, and [worked] with Marc of what he wanted the overall look to be... And then Walt, of course, would come and give his final approval on everything.”

Alice Davis developed the costumes for Disneyland attractions like it’s a small world and Pirates of the Caribbean.

In this exclusive interview, hear from Alice Davis about asking Walt about the costumes for the it’s a small world attraction.

Alice Davis: “The small world thing came off quite well, and it was strange, everybody wanted to have Walt’s approval of what they did in this—terrified to make any decisions for themselves and I was used to—if you’re doing a job and that, you make the decisions and you take the good or the bad, whatever comes with it...I made a few mistakes like I asked Walt how much my budget would be on costumes, and one eyebrow would go up and you knew you were in trouble, and he’d say, ‘I have a building over there filled with bookkeepers that find the money.’ He said, ‘I want the most beautiful costumes that every little girl, no matter what age she is,’ meaning ladies as well would love to have to play with themselves. So, he said, ‘I want just the most beautiful little costumes you can do.’ So, I had a field day because I was a Depression [era] child and I didn’t have dolls. So, I got the best dolls in the world to play with.”